How hard is life after prison? This simulation in Birmingham offers a taste

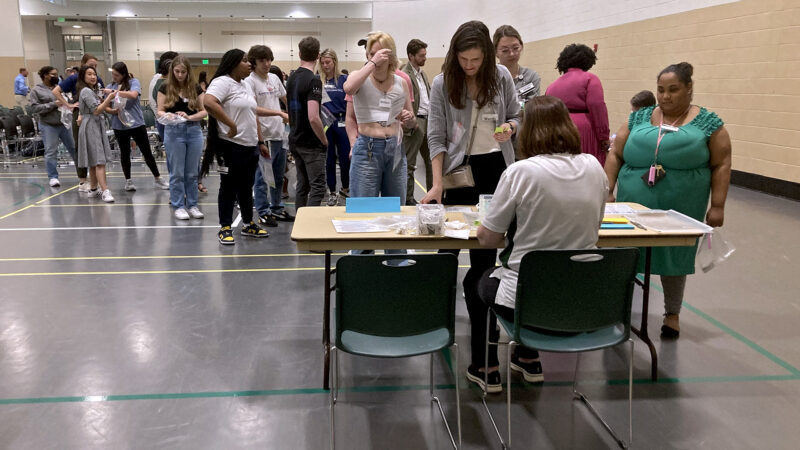

Participants stand in line to visit the courthouse station during a reentry simulation at UAB's recreation center, on March 24, 2023.

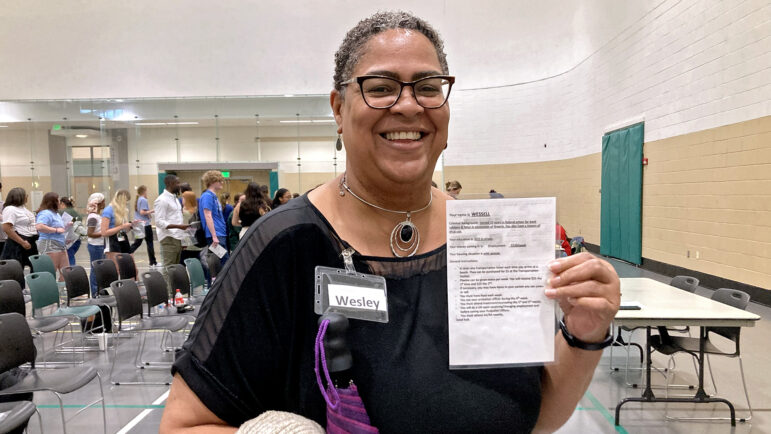

At least on the surface, Trionne Carmichael doesn’t appear to share many life experiences with Wessell.

She’s a full-time employee and student at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB). He’s spent the past 10 years in prison.

But for the next hour, Carmichael is walking in Wessell’s shoes in an effort to better understand what people like him experience.

“Let me see how hard it is, or how difficult it is, to see what they actually go through,” Carmichael said.

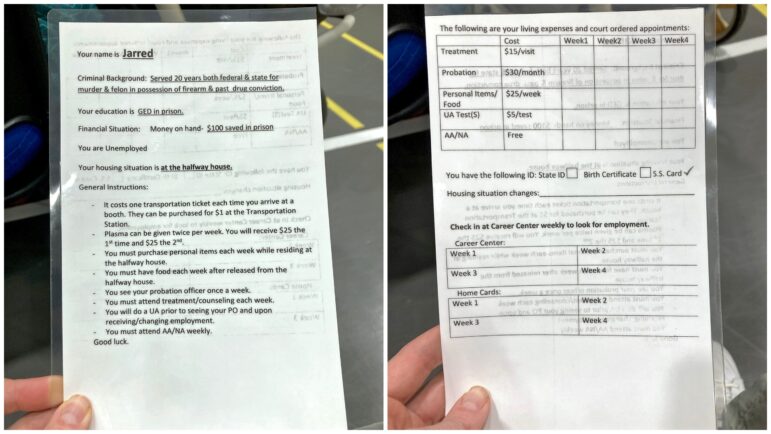

Wessell is fictional. He’s a character created for people like Carmichael to role-play.

But while he may not be real, Wessell’s scenario is rooted in reality.

Every day, hundreds of people across the Gulf South are released from prison. By many accounts, they’re set up to fail.

In Alabama, Carmichael is one of roughly 100 students and professionals who recently participated in a reentry simulation hosted by UAB and the U.S. Attorney’s office. It’s part of a nationwide effort to increase empathy for people leaving prison and envision a better way to reintegrate them into society.

It’s “one of the best teaching tools” to understand the barriers to regaining independence after incarceration, according to Alabama Assistant U.S. Attorney Jeremy Sherer.

“Reentry is inevitable,” Sherer said. “95% of the people who are incarcerated are going to eventually come out, and how they come out is wholly determinative by the systems we have in place.”

The idea behind the simulation is to highlight the gaps in the system, by mimicking the chaos and frustration of trying to regain stability after years in prison.

So much to do, so little time — and so few resources

Gathered in a large gym at the campus recreation center, the group buzzes with anticipation as participants prepare to begin the hour-long activity. Each person receives a list of tasks to complete at stations around the gym: visit the probation office, pay outstanding fines at the courthouse, find work at the employment office.

Most have little idea of what to expect.

“If I actually take on the persona of how they will feel, I’m coming out in a different world I don’t know anything about,” Carmichael said. “Can I adapt or adjust to what’s going on? Has prison got me ready to transition from prison back into society successfully, or will I be a failure and just go back?”

Just like in the real world, some participants leave prison with more resources than others, such as a few hundred dollars in savings, or a GED earned in prison. Others are returning home with family support and housing lined up.

But across the board, people begin the activity with a felony record, no job and no state identification. And they’re working against the clock. The simulation is divided into four 12-minute rounds, each representing one week.

When the game begins, the first stop for most people is the state ID station, which develops a line that is “a million years long,” in the words of one participant.

To further imitate the challenges of the real-life experience, a transportation card is required at every station. Representing a bus ticket or a car ride, it costs money, and it’s not the only unexpected source of debt.

By round two, Carmichael has figured out the complicated process of visiting the employment station to get a paycheck, which has to be cashed at a different station. But the money doesn’t last long. A visit to the courthouse quickly reveals that Carmichael owes $75 on an outstanding warrant.

“It is horrible out here, horrible,” she said.

By round four, things have not gotten much better.

“I don’t know whether or not I need to go get some food before I pass out or go get my paycheck,” Carmichael said. “I hadn’t paid child support. I hadn’t paid rent.”

Set up to fail

Reentry programs differ across the country, and states with higher incarceration rates, like Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, often have greater demand for services. But those services are few and far between.

“We simply don’t make use of the time that we have people incarcerated,” said Assistant U.S. Attorney Sherer. “And so they don’t have a plan when they come out.”

For years, Sherer has organized reentry simulations across Alabama for a wide range of audiences, including community groups, law enforcement officers and judges.

He said the goal is to not only highlight the barriers but also draw attention to possible solutions and evidence-based programs that could move the needle.

“The best practice model in reentry is reentry begins on day one,” Sherer said. “Making sure that people have resources once they exit the system, whether it’s a soft skill or whether it’s a tangible resource like a driver’s license or a real housing plan — a housing plan that’s just not a release to a homeless shelter.”

In Alabama, home to a prison system with 14 state facilities that house upwards of 16,000 men and women, Sherer said there is no organized system to prepare those people for reentry.

While Alabama prison officials have said that reentry is a priority, their main focus in recent years has been funding new prison construction.

A new perspective

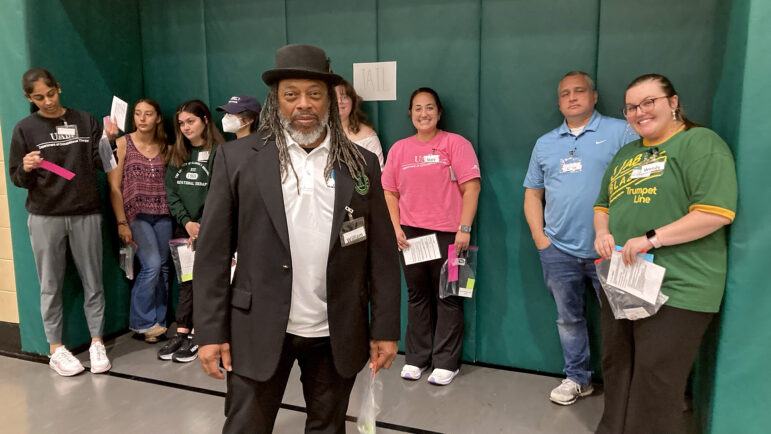

As the simulation winds down, Tim Lanier addresses the group.

“I want to thank y’all for making me feel good today. I like putting y’all in jail,” Lanier said as the crowd erupts in laughter.

Lanier served 18 years in Alabama’s prisons and is one of several formerly incarcerated people helping run the simulation. All fun aside he said, the activity is just a glimpse at how chaotic and stressful reentry can be.

“I really like the frustration I saw on the faces of the people that saw that they couldn’t get things done,” Lanier said. “You know, just imagine getting out of prison, after being in there over 15, 16, 18, 20 years. They give you $10 dollars and a bus ticket and tell you to come home.”

For participants like Carmichael, just an hour of the simulation is enough. She said there’s got to be a better, and safer, way to release people from prison.

“Basically you’re setting them up for failure,” Carmichael said. “They’re going back to prison, and they have no help. It’s like a hamster wheel going round and round with no progress.”

After she finishes her social work degree, Carmichael said she may work with formerly incarcerated people and help connect them to resources. It’s a small change, but one that will hopefully make the process a little bit easier for some people.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

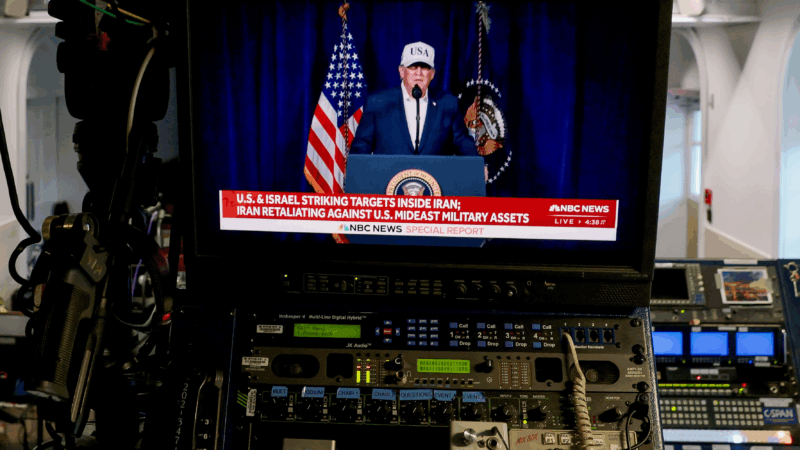

Here’s how world leaders are reacting to the US-Israel strikes on Iran

Several leaders voiced support for the operation – but most, including those who stopped short of condemning it, called for restraint moving forward.

How could the U.S. strikes in Iran affect the world’s oil supply?

Despite sanctions, Iran is one of the world's major oil producers, with much of its crude exported to China.

Why is the U.S. attacking Iran? Six things to know

The U.S. and Israel launched military strikes in Iran, targeting Khamenei and the Iranian president. "Operation Epic Fury" will be "massive and ongoing," President Trump said Saturday morning.

Sen. Tim Kaine calls on the Senate to vote on the war powers resolution

NPR's Scott Simon talks to Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., about the U.S. strikes on Iran.

Iran strikes were launched without approval from Congress, deeply dividing lawmakers

Top lawmakers were notified about the operation shortly before it was launched, but the White House did not seek authorization from Congress to carry out the strikes.

Political science expert weighs in on Iran’s nuclear program in light of U.S. strikes

NPR's Scott Simon speaks to Ariane Tabatabai, the Public Service Fellow at Lawfare, about U.S. attacks on Iran and how President Trump's calls for regime change might be received there.