Heat is the top weather-related killer. In Alabama, it may just be getting started

This story is part of a series “Alabama’s Hot Topic: What Climate Change Could Bring.” Read additional stories in the series.

Increased heat in Alabama impacts virtually everything. Take for instance, college football.

Chris Holloway is Tuscaloosa’s emergency medical services chief. During University of Alabama home football games, his team, which is part of the city’s fire department, helps manage medical emergencies at Bryant-Denny Stadium.

He noticed a change the past several years.

“We have seen an upsurge in heat related calls, when we’re working the Alabama football games,” Holloway said.

Holloway, who’s been with the fire department for more than 27 years, remembered one game in 2019.

“We actually had over a hundred calls for people that were overheated before halftime of that game. It was crazy,” Holloway said. “Most of these people just needed to get in the shade for a few minutes and get hydrated.”

He pointed out part of the reason for more emergency calls is just simple math. Due to multiple expansions, the stadium can now hold about 16,000 more people than it did at the turn of the 21st century.

But he gives the university credit for what he calls being proactive. UA has recognized the increase in heat-related illnesses and in recent stadium renovations, added facilities to help keep spectators from over-heating.

“We’ve really just had more and more issues over time with fans getting hot,” said Brandon Sevedge, director of athletic facilities at UA.

He said the school has added seven of what he calls “dedicated cooling stations” in the stadium that include fans, first aid personnel, and large tanks called “water monsters” that hold about 600 pounds of ice and 125 gallons of water each.

It’s all because of the heat.

And Bryant-Denny Stadium isn’t alone. He said the water monsters and fans are an amenity at lots of SEC football stadiums now.

The warming hole

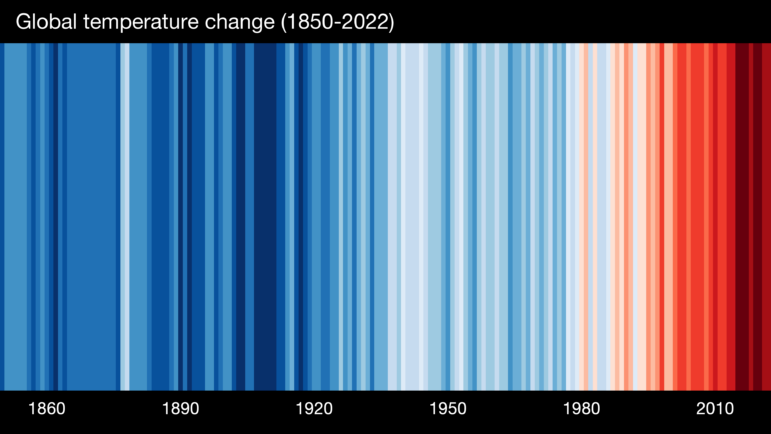

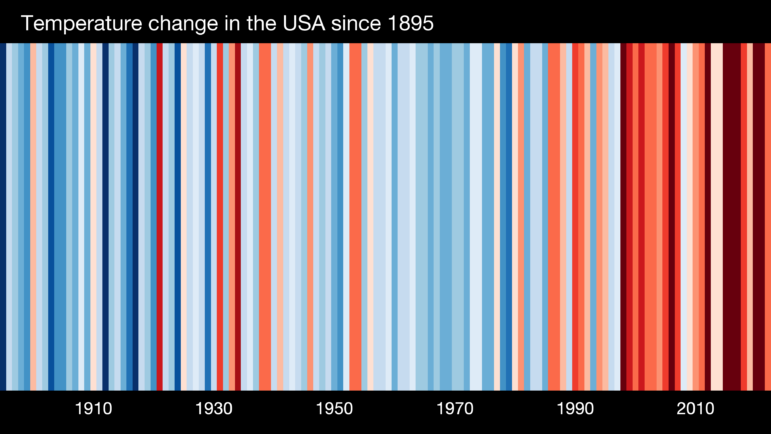

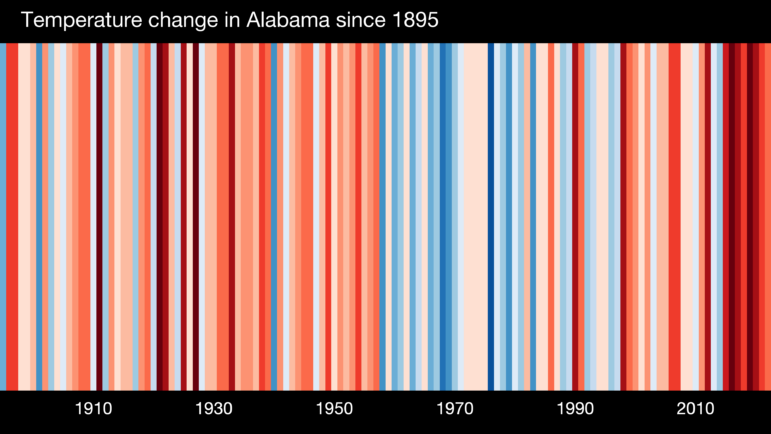

On average, global temperatures have steadily increased since fossil fuels began to be widely used. The graphic above is a “warming stripe” which represents global temperatures from about 1850. Blues indicate cooler years; the colder, the darker the stripe. Red stripes show warmer temperatures; the darker, the hotter. Whites are in the middle of the temperature spectrum.

Comparing these graphics offers an easy way to see differences in temperatures across the planet. For instance, differences emerge when comparing the global stripes to those of the U.S.

However, compare both of those graphics to Alabama’s stripes and the differences are stark. Alabama was considerably warmer in the first half of the 20th century, which one might expect of a southern U.S. state. Yet, in the 1960s and ‘70s, the state cooled, before trending up fast, beginning about 2000.

That’s often referred to as the “warming hole,” a section of several southeastern states, with Alabama sitting in the middle, that have not seen an increase in average temperatures since the late 1880s. Scientists attribute this phenomena to atmospheric cycles driven by the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, along with particles of soot from smokestacks and tailpipes, which can block some of the sun’s intensity.

Those types of pollutants were curtailed by environmental policies and shortly afterwards, in the 1980s, temperatures began to rise.

The reasons are still being studied, but many researchers believe there are two main causes: less sun-screening particulate pollution and continued increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping greenhouse gasses.

It’s getting hotter in Alabama

Now, several indicators show Alabama appears to be making up for lost time. The latest data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), shows, for the first time, a slight increase in average temperatures since around of the turn of the 20th century.

Katherine Hayhoe, a climate scientist and professor at Texas Tech, noted a spike in recent temperatures, although it’s not yet a statistically significant increase.

“The last eight years have actually been quite warm. And so that has finally started to push things up,” Hayhoe said.

However, other indicators show significant jumps in temperatures. According to NOAA, 2016 to 2020 was the warmest consecutive 5-year period on record for Alabama. And it’s expected to get even hotter, with up to four times the number of 95-degree days over the next several decades compared to what we see now.

Another statistic buried in the Fourth National Climate Assessment, a report on climate change that includes input from NOAA, NASA, and the U.S. Department of Energy, lists Birmingham as one of only five large U.S. cities that have increasing trends exceeding the national average for all aspects of heat waves: timing, frequency, intensity, and duration.

Kenneth Kunkel is a marine, earth and atmospheric professor at North Carolina State University, and he was an author of the Fourth National Climate Assessment. He said one of the reasons Birmingham ranked so high on that list was because the study looked at both heat and humidity.

“It took into account the fact that in the Southeast, humidity is a really big thing,” said Kunkel. “That’s one of the reasons why our summers are so uncomfortable.”

Greatest public health threat

Humidity is also a reason why the heat is so dangerous. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, heat is the leading weather-related killer in the U.S.

Dr. Paul Erwin, Dean of the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Public Health, said the rise in temperatures is a big stressor on the human body.

“Climate change, in my estimation, is the greatest public health threat that we will face in my lifetime,” Erwin said. “Larger than COVID.”

To address those threats, UAB has hired five new professors to focus on the impact of climate change on human health. Erwin added heat is an occupational health problem, and he plans to work with employers who have employees outside for extended periods.

“Changes in in their work standards need to be considered regarding the length of time workers are exposed to extreme heat,” said Erwin.

A 2021 report from the Union of Concerned Scientists backed up that assertion. It projected by the middle of this century, outdoor workers risk losing 22 workdays on average annually due to extreme heat, up from three days historically. That means a potential loss each year of $2,800 for the average outdoor worker and $1.2 billion annually in total earnings in the state.

While the heat on its own is a huge threat to health, Erwin said hotter temperatures also increase the risk of vector-borne diseases from a variety of insects.

“Ticks and mosquitoes are able to overwinter at higher and higher latitudes,” allowing them to live longer and multiply in greater numbers,” Erwin said. “That certainly increases the potential of human exposure to those vector-borne diseases.”

The urban heat island

Rising temperatures are more dangerous in urban areas, where hard surfaces tend to make it hotter during the day and keep it sweltering at night.

“At least when it cools down at night, somewhat, your body gets some relief,” said Dr. Walter Schrading, an emergency medicine professor at UAB. “And then you’re better able to withstand, again, another very hot day the following day.”

But continued exposure to heat just wears the body down, Schrading said, especially for those who don’t have access to air-conditioning.

“That progressive heat stress over days is what leads to the morbidity and mortality of heat stroke in urban environments during heat waves,” he said.

To mitigate those effects, Schrading said it’s critical that cities make significant changes, such as turning some parking lots into parks and planting trees along streets. It’s especially important for under-resourced communities, where people are less likely to have air-conditioning.

“We need to take measures to do whatever we can to combat global warming, because otherwise, parts of the world that previously were habitable are no longer going to be habitable by humans,” Scharading said.

If we need proof, Schrading said, look to Europe where a heat wave in 2003 killed upwards of 70,000 people.

The hidden cost of oil: Families fractured by a pipeline project

As the 900-mile East African Crude Oil Pipeline project takes shape in Uganda, there is the promise of economic benefit. But it's shaking up the lives of some 100,000 people.

Why some see the dollar’s drop as a sign America is losing its financial might

The dollar has just posted its worst first-half of a year since 1973. And now investors wonder — is it a sign that America is losing its financial standing?

What’s the best Pixar movie? Here’s what our listeners said

People have strong opinions about the best Pixar movies. We asked NPR Pop Culture Happy Hour listeners to vote.

‘The worst day of my life:’ Texas’ Hill Country reels as deaths rise due to floods

Dozens of people have died in the Texas Hill Country. Scores of others are missing or unaccounted for. As rescue crews continue to search for victims, those who survived are coping with the loss.

Are seed oils actually bad for your health? Here’s the science behind the controversy

Health Secretary RFK Jr. has said vegetable oils, like canola and soybean, are 'poisoning Americans.' But many researchers say the evidence isn't there. So, what does the science say about seed oils?

Trump plans to share new tariff rates this week as deadline for deals approaches

The administration keeps shifting its plans when it comes to trade negotiations. The latest expectation is that most countries will receive new tariff rates this week that would go into effect on Aug. 1.