An inside look at an AP African American Studies class

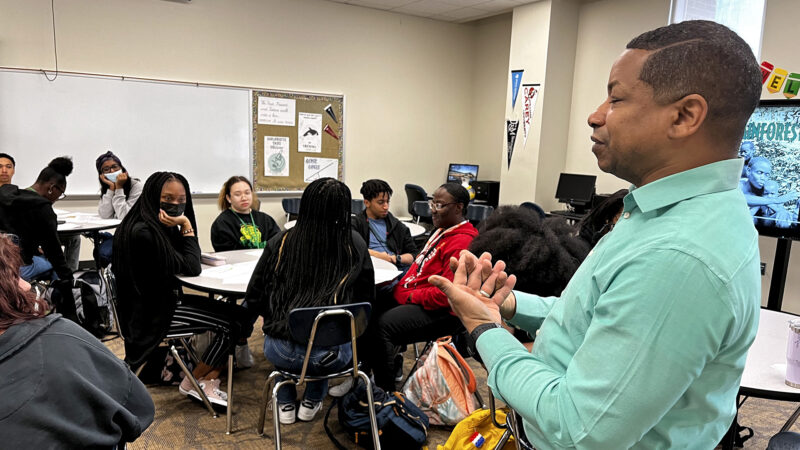

Emmitt Glynn leads the AP African American studies course at Baton Rouge Magnet High School in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on March 2, 2023. It is one of 60 schools piloting the course nationally.

The steading rhythm of djembe drums envelops Emmitt Glynn’s classroom in Louisiana’s Baton Rouge Magnet High School.

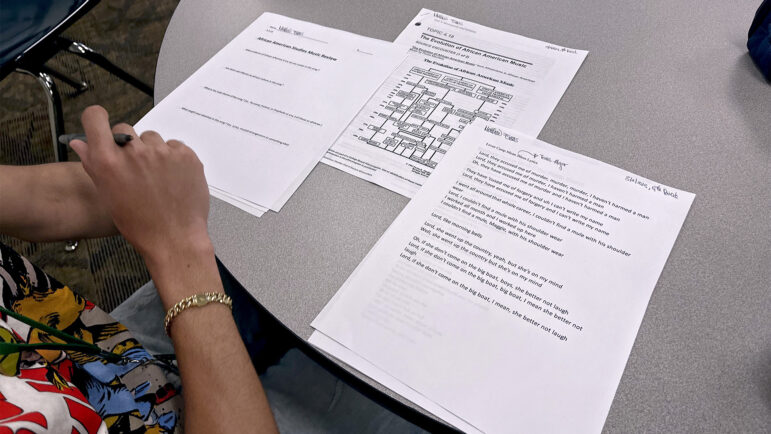

Today’s Advanced Placement (AP) African American Studies lesson is on the evolution of African American music, so Glynn has brought in a group of music students to demonstrate how beats from the African continent made their way into African American music genres like blues, jazz and hip-hop. The drummers sit in a semicircle wearing dashikis as their hands move in harmony layering beats until the whole room is filled with sound.

The students take notes at their desks and bob their heads to the music while Glynn looks on, recording, with a smile.

“I feel like a West African griot in a sense because I’m bridging some generations together,” Glynn said. “It’s kind of really neat.”

Glynn’s class is one of 60 schools piloting the African American Studies course nationally and one of only two in the Gulf South region. Last year, when the College Board announced the course, Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis made headlines when he called to ban AP African American Studies in Florida schools to be in compliance with the state’s ban on critical race theory. Similar pushback has come out of Arkansas and Virginia.

Still, the students in Glynn’s class said they love the course and learn a lot from it. Normally, students receive college credit for AP classes, but since this semester is a trial run they won’t — and 60 students still chose to take it.

Why students are taking the course

One of those students is junior Jamiya Lavergne. She’s Black and said she took the class to feel closer to her cultural roots.

“I took it because I know who I am, but when I take this course it’s like what makes me who I am?,” Jamiya said. “What comes with the Black experience? What is the Black experience? And [the class] just goes above and beyond things that regular history can’t touch.”

She doesn’t understand the opposition to this class because she said African American history is American history.

“It’s not like it’s biases being forced upon us. We can build our own opinions about certain things,” Jamiya said. “It’s really no harm in learning about any form of history because history is uncomfortable learning about in general. So what’s the difference between learning about African American history as opposed to American history or European history?”

Her classmate Ella Blandino, who’s white, wanted to better understand the world and society.

“I definitely feel like it made me more able to notice prejudices in other people,” the senior said. “I saw things that I might have thought were weird before, but now I can connect why I think that or why I feel that way. And it helps me to be more assertive because I know where it’s coming from.”

Ella said she likes being able to bring what she learned in class into her relationships with other people — like a candid conversation about African American art with her parents.

“I love to hear people’s perspectives in our class and also just in the world,” Ella said. “Any time that we talked about communities coming together… I always liked that.”

The College Board vs. politics

This course almost wouldn’t have been possible in Louisiana, too. In 2021, a bill to ban critical race theory and teaching systemic racism was rejected mid-session when state Rep. Ray Garofalo, former chair of the Louisiana House Education Committee, said that the “good” of slavery should be taught along with the “bad.” Garofalo was soon ousted as chair and the bill died. Garofalo introduced bills aimed at banning the teaching of critical race theory in 2022, but they were killed in committee.

When Glynn was asked to teach this course he was excited to collaborate with the College Board and other invested teachers.

“I expected a normal release and launch of a course like other courses that have been launched by a College Board such as AP Chemistry or AP Spanish,” Glynn said.

He was shocked to see so much media attention and political backlash directed toward this course.

“I thought that we were schoolteachers and we were teaching history, and this is American history,” Glynn said. “So why is it so shocking to want to teach history to young people who should know the history of the nation they live in?”

Gov. DeSantis’ administration said the AP African American Studies curriculum has a political agenda “on the wrong side of the line for Florida standards.” This is also against the backdrop of bans on critical race theory and divisive concepts in K-12 schools that were enacted in Alabama, Mississippi and other Republican lead states.

In February, the College Board, which oversees the AP program, said its commitment to AP African American Studies is unwavering despite perceived mixed messaging when it stripped down the course curriculum in response to Florida’s ban. The College Board said planned revisions to the course are part of the normal process of a pilot program. It also apologized for not expressing this support before Republican lawmakers used the planned revisions as another point in their political strategy.

“We deeply regret not immediately denouncing the Florida Department of Education’s slander, magnified by the DeSantis administration’s subsequent comments, that African American Studies ‘lacks educational value,’ the College Board said in a statement. “Our failure to raise our voice betrayed Black scholars everywhere and those who have long toiled to build this remarkable field.”

Glynn, who’s been teaching for 29 years, said he hopes all students are able to take this class if they want to. He’s also had a lot of outside support from the community.

“We had so much interest in this course. I have had adults who have asked to take this class. They said they’d love to come and sit in just to learn,” Glynn said. “I bring in a lot of local history from things that my family shared with me as a child, from things that I’ve learned living in this community my entire life and from just different people in the community.”

That local history includes topics like the 1972 Baton Rouge race riots or the historic Temple Theater where Ella Fitzgerald and Duke Ellington played. Glynn said he believes the future of this course is bright.

A positive impact

For students, taking the AP African American Studies course could have a greater positive impact academically than simply boosting their GPA or earning college credit in high school.

Stephen Finley, the chair of the African and African American Studies department at Louisiana State University, said the course can help round out their education.

“Having prior knowledge of African studies and African American history specifically could only help when they got to college,” Finley said. “And it wouldn’t just help in African-American studies courses. It would help them understand their other courses so much better.”

In his experience, Finley said most students who aren’t AAAS majors don’t encounter an AAAS class until they are upperclassmen, which he said puts them at a disadvantage to deeply understand topics in the humanities and sciences.

He also said high school students who learn African American studies in the South have a unique privilege.

“In other spaces, it has to be explicit sometimes before we recognize it. In the South, it’s everywhere,” Finley said. “I grew up in Southern California. I live in Louisiana, where down the street a mile and a half is a former plantation. In California, you don’t have those visible symbols, for example, as one does here.”

Empowering for students

For Kahlila Bandely, Mr. Glynn’s class has been an empowering learning experience.

“I speak to my mom about this and she’s like, ‘Huh? I wish I could have taken that when I was your age,’” Kahlila said. “My mom grew up in New York. So their history and legacy is a little bit different. But she says she can still resonate with a lot of the things that we’re discussing in this class.”

In her previous history classes, Kahlila said she and other students with marginalized identities felt brushed over. But this class is different. She said she and her peers can have open discussions and she gets to learn about things she cares about, like Black feminism. She said she would never get to analyze Beyoncé’s song, “Black Parade,” as an example of the evolution of African American music in any other history class.

“It makes me think about the fact that at one point our school was segregated and I wouldn’t have been given this opportunity,” Kahlila said. “So I feel just incredibly grateful to be able to take this course in general. And then being a Black student taking it, it’s even more grateful.”

The AP African American Studies pilot will start its second trial next school year. Glynn said he already has a lot of interest from more students in the course.

Kyra Miles is a Report for America corps member covering education for WBHM.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

U.S. and Iran to hold a third round of nuclear talks in Geneva

Iran and the United States prepared to meet Thursday in Geneva for nuclear negotiations, as America has gathered a fleet of aircraft and warships to the Middle East to pressure Tehran into a deal.

FIFA’s Infantino confident Mexico can co-host World Cup despite cartel violence

FIFA President Gianni Infantino says he has "complete confidence" in Mexico as a World Cup co-host despite days of cartel violence in the country that has left at least 70 people dead.

Supreme Court appears split in tax foreclosure case

At issue is whether a county can seize homeowners' residence for unpaid property taxes and sell the house at auction for less than the homeowners would get if they put their home on the market themselves.

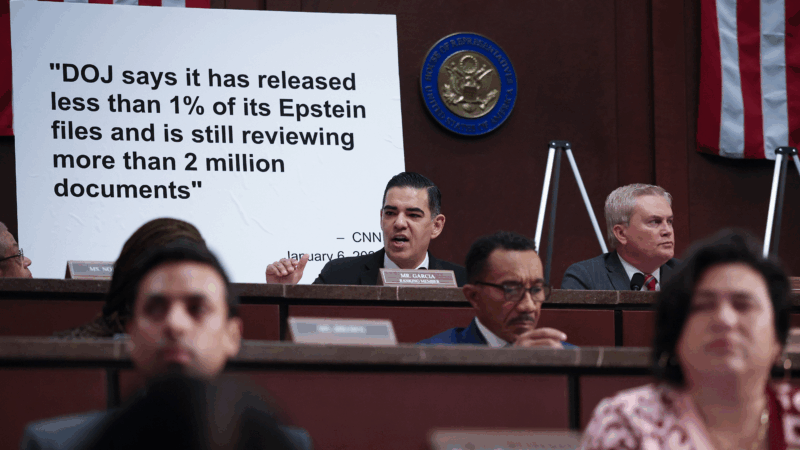

Top House Dem wants Justice Department to explain missing Trump-related Epstein files

After NPR reporting revealed dozens of pages of Epstein files related to President Trump appear to be missing from the public record, a top House Democrat wants to know why.

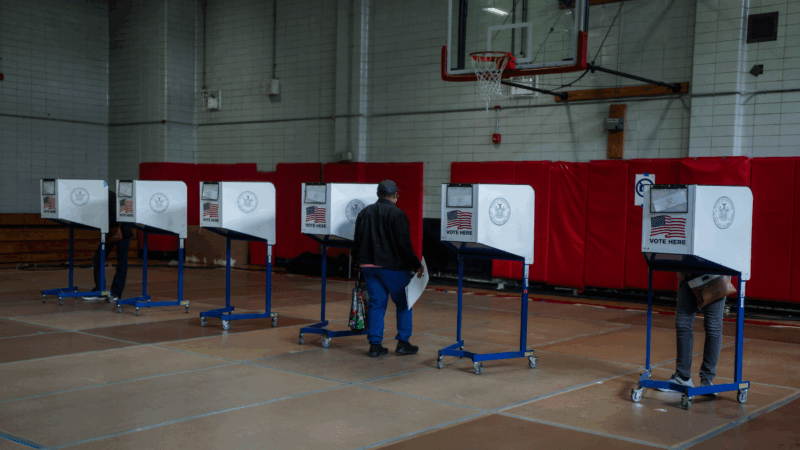

ICE won’t be at polling places this year, a Trump DHS official promises

In a call with top state voting officials, a Department of Homeland Security official stated unequivocally that immigration agents would not be patrolling polling places during this year's midterms.

Cubans from US killed after speedboat opens fire on island’s troops, Havana says

Cuba says the 10 passengers on a boat that opened fire on its soldiers were armed Cubans living in the U.S. who were trying to infiltrate the island and unleash terrorism. Secretary of State Marco Rubio says the U.S. is gathering its own information.