Critical race theory divides Gulf South educators and state leaders

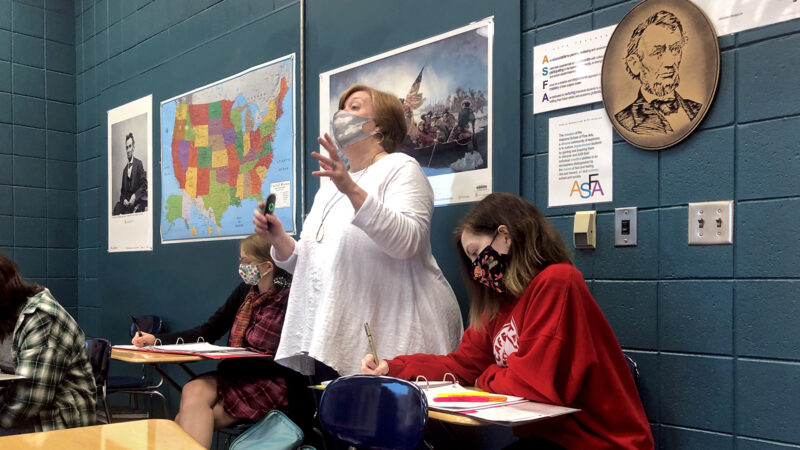

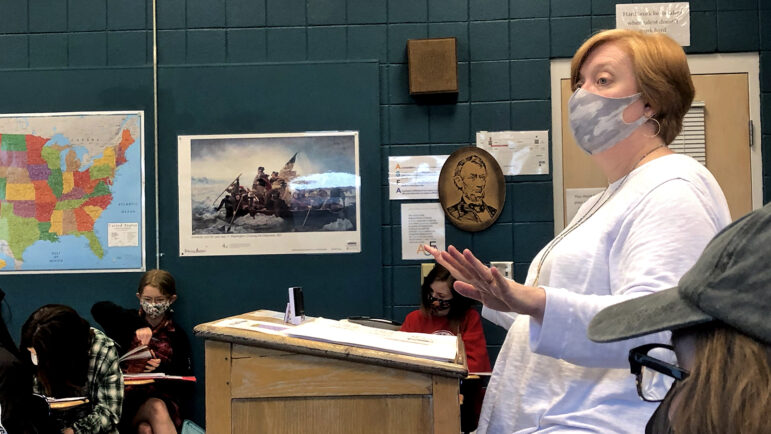

In her early American history classes, Annemarie Gray believes in teaching the good, the bad, and the ugly to her students at the Alabama School of Fine Arts.

Every time Annemarie Gray begins teaching a new unit in her history class, she changes the posters on the walls of her classroom at the Alabama School of Fine Arts in Birmingham.

They currently feature Andrew Jackson and maps showing what’s known as the Trail of Tears. For the next lesson, she’ll put up photos of abolitionists who fought for the end of slavery.

Gray, who is white, says telling the whole story has always been important in her lessons.

“I’ve always sort of said that when it comes to teaching American history, I teach the good, the bad and the ugly,” Gray said. “Frankly, I would challenge anyone to come into my classroom and tell me that I’m teaching anything that isn’t the truth.”

But in Alabama, Mississippi and other parts of the country, the truth of American history is being challenged because of a concept that’s becoming a political football across the country — critical race theory.

The American Bar Association outlines critical race theory as an academic concept that examines the role of race and racism as an inherent part of systems in America. Politicians against critical race theory argue that certain topics could make students uncomfortable or believe that one race or sex is inherently better than the other.

While critical race theory has not been taught in K-12 schools and is reserved for classes in higher education, that has not stopped Alabama state leaders from making it a hot button issue over the past year.

The Alabama Department of Education banned teaching the topic in K-12 schools last summer, and new legislation introduced in the state’s 2022 legislative session would prohibit teaching “divisive concepts regarding race or sex,” in higher education as well. Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey even focused a part of her campaign for re-election on dismissing critical race theory — highlighting the K-12 ban in a commercial that aired during the NCAA Southeastern Conference football championship game between the University of Alabama and the University of Georgia in December.

Teachers, however, worry that the debate over critical race theory is overshadowing staffing shortages and learning loss — issues they believe are more important to students’ learning. Some teachers also worry their jobs will be threatened. One of the bills in Alabama would require public K-12 schools and universities to fire employees who teach certain concepts regarding race or sex.

“We shouldn’t be shackling teachers and making them afraid to have these conversations,” Nefertari Yancie, a Black social studies teacher at Clay-Chalkville Middle School, said. She believes having discussions about racism in history with students is essential.

“It doesn’t matter what bill or what resolution you put in place, they’re going to ask the question. So why are we avoiding having the conversation?” she said.

How other Gulf States are handling CRT

Alabama isn’t the only state in the Gulf South attempting to pass legislation prohibiting critical race theory.

Last week, all Black lawmakers in Missississipi’s state senate walked out of the Legislature’s chambers in protest of a bill that would prohibit how race is discussed in public schools, including topics related to critical race theory.

“We don’t need to waste our time taking up a bill, looking for a solution for a problem that doesn’t exist,” said Sen. Derrick T. Simmons, the senate minority leader who was part of the walkout.

Black members of Mississippi’s senate walk out of the chamber before the final vote on a bill to ban teaching critical race theory in schools and universities. The vote passed. pic.twitter.com/hLUwAn6ekL

— Kobee Vance (@kobeevance) January 21, 2022

The bill passed anyway and is headed to the Mississippi House of Representatives. But attorney Robert McDuff, with the Mississippi Center for Justice, says even when bills that limit teacher speech do pass, they rarely go anywhere.

“I think the states of Mississippi and Alabama and other states who are considering these laws should really avoid wading into that swamp because it’s simply not worth it,” McDuff, who is white, said. “The problem they claim exists really doesn’t and it’s a mistake for politicians to get into the business of telling teachers what they should teach in the classroom.”

The seasoned attorney also said that these bills usually run afoul of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution and he predicts the long and costly lawsuits usually result in the state governments losing and having to pay for the legal battles.

In 2021, Louisiana Rep. Ray Garofalo proposed a similar bill that would end the teaching of “divisive concepts” in Louisiana colleges, including the idea that Louisiana and the U.S. are inherently racist.

“Critical race theory demands a new kind of segregation that divides people based on their race and the color of their skin. It furthers racism and fuels hate,” Garofalo said during a legislative session in April 2021.

In that same session, Garofalo, who is white, also made a comment about teaching the “good” in slavery and his argument for banning critical race theory disintegrated. Garofalo’s proposal and comment were condemned by Louisiana’s Legislative Black Caucus and Gov. John Bel Edwards and resulted in him being removed from his position as chairman of the Louisiana House Education Committee.

‘History shouldn’t be a resume’

Regardless of what happens at the legislature, it won’t change how some educators teach history. Gray said she’ll continue to promote critical thinking skills for students and generate healthy discussions.

“I don’t think telling the truth is divisive,” Gray said. “I don’t think anybody, certainly no teacher that I know, is trying to teach students to hate the United States of America or to hate white people. We’re trying to show the history of this nation.

“It can be scary, but it’s not going to change what I do. I’m not going to miss a beat.”

It’s also been suggested by local activists to allow teachers to do their jobs without extra oversight from the state governments. John-Paul Chaisson-Cardenas, the civil rights fellow at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, suggests it should be a local decision.

“I believe in teachers,” he said. “I believe that teachers have the skills to be able to teach this content in a way that their students can understand and digest. It doesn’t have to be controlled at the state level.”

Barry McNealy, who is Black, is the historical content expert at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute and a social studies teacher at Parker High School. He said it’s important for students to learn what to do from history, but also what not to do.

“History shouldn’t be a resumé. It shouldn’t be something that we edit to stray away from things that are uncomfortable,” he said. “Life is uncomfortable and if we take out those parts of history that are challenging and uncomfortable, then it really negates the purpose of teaching it in the first place.”

McNealy recently spoke at a seminar called “Protect the Truth in Education” sponsored by the institute, Project Say Something and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Legal Defense Fund that gathered education advocates from around the state to discuss concerns and strategies to fight back against the legislation.

“Someone said to me that you should never lie to children because they’ll live long enough to find the truth,” he said. “And I don’t see a place in my future where I would be willing to tell children things that weren’t true.”

The Alabama legislature will discuss its bills related to critical race theory later on in the session, and Mississippi is doing the same. Louisiana legislators have yet to pre-file any bills this year related to the issue.

Kyra Miles is a Report for America corps member reporting on education for WBHM.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Birmingham, Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

In the Texas flood zone, volunteers help reunite lost pets with their owners

Hundreds of pets have been reported missing after the devastating floods in central Texas. Volunteers have been combing through debris to help reunite them with their owners.

Here’s a list of Trump’s tariff letters so far and the rates they threaten

Finding it hard to track the latest U.S. trade policy state of play? Here's a look the deals the president has announced and the rates he's so far threatened to impose in letters to global leaders.

Trump praises disaster response in Texas while FEMA’s future is murky

The president and first lady visited Kerrville to meet local officials and families of the victims of the recent flooding. Trump promised federal support, but his team emphasized the state's role.

Where to find information about flood risk to your home

Many people in the United States receive little or no information about flood risk when they move into a new home or apartment. Here's how you can learn about your flood risk.

‘Helping every dang soul’: Beloved camp director was among those lost in Texas flooding

Jane Ragsdale ran the Heart O' the Hills camp for girls in Kerr County. The camp was between sessions when the deluge hit. The only person killed there was Ragsdale.

Federal judge orders stop to indiscriminate immigration raids in Los Angeles

Civil rights groups alleged that ICE and Border Patrol agents are rounding people up based on their race, and denying them access to lawyers. A federal judge said there's evidence what they're doing is illegal.