Confrontations between Alabama miners, strikebreakers a part of a rough labor history

Coal miners on strike stand in line to pick up their strike checks on March 23, 2022, in Brookwood, Alabama.

Every two weeks on the grass and gravel outside a United Mine Workers of America union hall, miners sing happy birthday to their kids, eat hot dogs and announce the names of members who have died since the last rally.

But the camaraderie in the parking lot contrasts with the tension in the small town of Brookwood, Alabama. Miners wear shirts that read “no luv for scabs” — slang for workers who have crossed the picket line — and cheer as a local union leader tells a story of threatening one of those strikebreakers at a gas station.

“I said, ‘I’m going to beat your eyes out and then blow your brains out,’” Larry Spencer said as the crowd laughed in March. “‘Because I’m tired of you taking my brothers’ and sisters’ jobs.’”

The strike at the Warrior Met Coal-owned mines in Brookwood, where hundreds of these union workers are employed, is on its 16th month and counting. During that time, the strike led to fist fights, flattened tires and shattered car windows. Now, the United Mine Workers of America union is fighting a $13.3 million dollar fine that’s, at least in part, for the property damage. The confrontations on the Warrior Met Coal picket line make up the latest chapter in a long, rough history of conflict between miners and companies that explain why some historians call the U.S. labor movement one of the bloodiest.

More than a year of striking and conflicts

The Brookwood miners’ frustrations all started with the price of steel — made from the type of coal these workers mine — plummeting in 2016. Walter Energy, which ran the Brookwood mines at the time, went bankrupt. In its place, Warrior Met Coal was formed by the debt owners to run the mines and offered the workers a deal — take a cut on pay and benefits so the mines could afford to stay open, or risk losing their job. The miners agreed to the cuts.

Now, steel prices are booming, amidst tariffs on Chinese steel and a global construction surge prompted by COVID-19 stimulus packages. But Warrior Met Coal isn’t offering enough to restore what the miners gave up — causing the strike.

Once the strike began in April 2021, the miners regularly formed picket lines outside the many entrances to the Warrior Met Coal mines, stretched out over dozens of miles weaving through the backwoods of Brookwood. Miners set up grills and built makeshift shacks to protect themselves from the sun during the long hours they would be protesting. They joked together on lawn chairs between the mine’s shift changes to pass the time.

But videos released from Warrior Met Coal show a shift in demeanor when strikebreakers try to pass them. One edited video, just under four minutes long, appears to show multiple scenes involving miners tossing a cement block through a car’s rear window, swarming a bus full of strikebreakers and the presumed aftermath of fights that left the faces of workers bloodied. A separate video shows security camera footage of a fistfight.

Seven months into the strike, a Tuscaloosa County judge prohibited strikers from picketing outside of the mine entrances. Those restrictions have slowly loosened up, but miners must now provide their full name and address before going to the picket line.

The union later agreed to settle and pay a fine from the National Labor Relations Board to cover damaged vehicles and one worker’s medical bills. Federal labor officials estimated the penalty would be around $400,000, according to the union. But in July, Warrior Met Coal instead insisted the union pay $13.3 million to cover the cost of extra security, transportation, cameras and lost revenue for unmined coal.

In a recent report, Warrior Met said the strike cost the company $8 million in the second quarter of 2022 for things like increased security and idle mines. But that didn’t stop the company from also reporting $297 million in net income — a record for the company.

The union is fighting the company’s claim, calling it ridiculous.

“The company is supposed to suffer because of the fact that workers aren’t working,” Cecil Roberts, president of the United Mine Workers, said while referring to the idle mines. “This is a total reversal of what the NLRB is supposed to stand for.”

History’s mine wars

Strikers in Brookwood are mostly accused of smashed windows and flattened tires. And while that’s nothing to minimize, it’s also not comparable to the historical violence around labor rights in the U.S. — especially at coal mines around the late 1800s and early 1900s.

“There was a tremendous amount of violence around labor relations and partly because there were so few laws,” said Lou Martin, co-founder of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum.

Some of the most violent conflicts were part of the West Virginia Mine Wars, which took place in the early 1900s. About 10,000 miners formed the Red Neck Army and took up arms against the Logan Defenders, made up of local and state police alongside mercenaries hired by the coal companies. At the largest conflict, the Battle of Blair Mountain in 1921, about a dozen miners were estimated to have been killed.

While it can be difficult to determine who shot first in these conflicts, historians said the companies were often to blame. And while the workers fought back, they were usually the ones killed.

Labor law and order

A little more than a decade after the Battle of Blair Mountain, the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 was passed — causing a decline in these types of conflicts, according to labor history author Colin Davis. The law added protections for collective bargaining, giving workers a new, legal route to fight — no longer physically — for their rights.

“Once they got that, the level of violence plummeted,” Davis said.

It also required companies to negotiate in good faith with unions and added consequences for those that didn’t.

But while violence declined after the law’s passage, it didn’t completely end. In 1937, Chicago police fired into and attacked a group of steelworkers and their supporters, killing 10 strikers in what’s known as the Memorial Day Massacre. Video of the event and the outrage that followed would lead to a further decline in violence, according to Martin.

“One of the things that made that incident so important is that it was on film,” Martin said. “Members of Congress were able to see that shooting and they saw that the police were shooting strikers and family members in the back.”

Historians also credit World War II for cutting back on violence around unions, since the government required companies to accept unions in exchange for lucrative government contracts.

Protections breaking down

While the National Labor Relations Act is still in effect today, the law hasn’t been updated in 87 years. During that time, companies have discovered plenty of ways around negotiating.

Over the past year, more than 200 Starbucks have voted to unionize while an Amazon warehouse in Staten Island did the same. But despite the big election wins, none of the newly-unionized workers have negotiated a first contract yet. That process can take years — if it happens at all.

Starbucks has also been accused of union busting in recent months in an attempt to quell efforts at other stores trying to organize, including firing some pro-union workers. The NLRB has been successful in convincing a federal judge to force the coffee giant to reinstate seven fired pro-union workers at a Memphis store, but other fired Starbucks workers are still fighting to get their jobs back.

Historians say the labor protections have been weakening for decades, contributing to union membership being tied for its lowest number in 2021. But they also say turning to violence is a bad idea for the labor movement and leads to more restrictions on strikers, like the injunction in Brookwood that’s kept miners from picketing by the mines.

Miner Aaron Parker agrees that going after strikebreakers is a mistake. He’s still friendly with many of the workers that have crossed the line and talks to them on the phone. But if one of those workers gets a car window smashed in, Parker doesn’t care — they’re undermining the union and miners who are holding the picket line.

“I have no sympathy for their misfortune because I’m going through misfortune every day,” Parker said.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration among Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama and WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

Class-action lawsuit filed after the Potomac sewage spill

A class-action lawsuit has been filed after part of a decades-old sewer line in Maryland collapsed in January, sending raw sewage into the Potomac River. After weather delays, repair work has resumed.

Kennedy Center president departs – months before the art complex’s scheduled closing

In a post on Truth Social, President Trump announced Friday afternoon that Richard Grenell is leaving the Kennedy Center. The arts complex is scheduled to close in July for renovations.

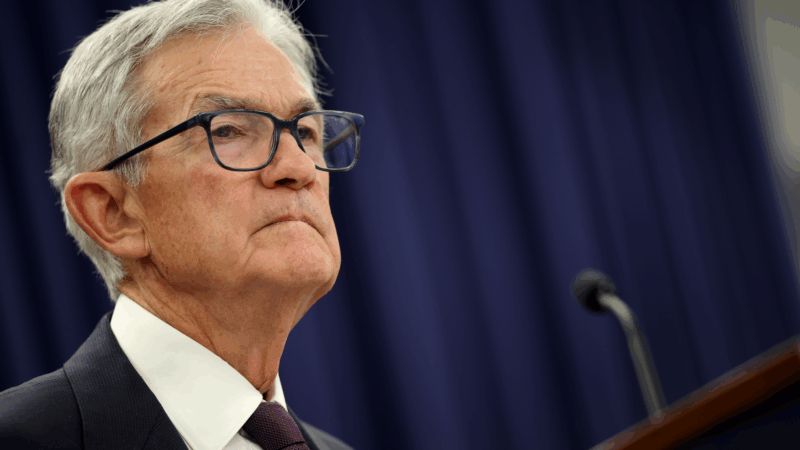

Judge blocks DOJ’s criminal probe of Federal Reserve, blasting it as political

A federal judge has put the brakes on a criminal probe of the Federal Reserve, saying it was part of an improper campaign by the Trump administration to pressure the central bank into cutting interest rates.

A cholesterol test you’ve never heard of is now recommended to prevent heart disease

The test can help assess your lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease. That, along with earlier treatment for high cholesterol, is part of new doctors' guidelines.

And the Oscar goes to — wait, why is it called an Oscar?

The Academy Awards officially adopted the "Oscars" nickname in 1939. But who is Oscar, and who started calling them that? We may never know. But here are four enduring legends to consider.

TSA workers miss a full paycheck, while travelers keep paying airport security fees

Many TSA workers received no money in their paychecks Friday as the partial DHS shutdown drags on. Fees paid by airline passengers keep piling up, even as airport security officers work without pay.