Alabama coal miners begin their 20th month on strike

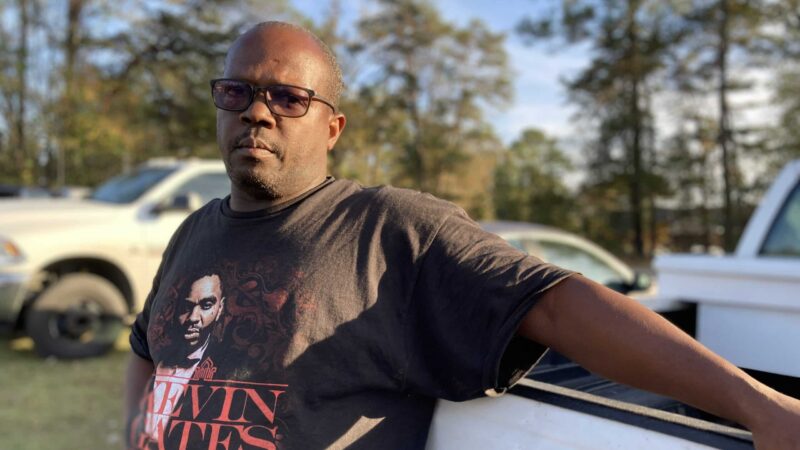

Antwon McGhee is one of about 500 Warrior Met Coal miners in Brookwood, Ala., who have been on strike for 20 months.

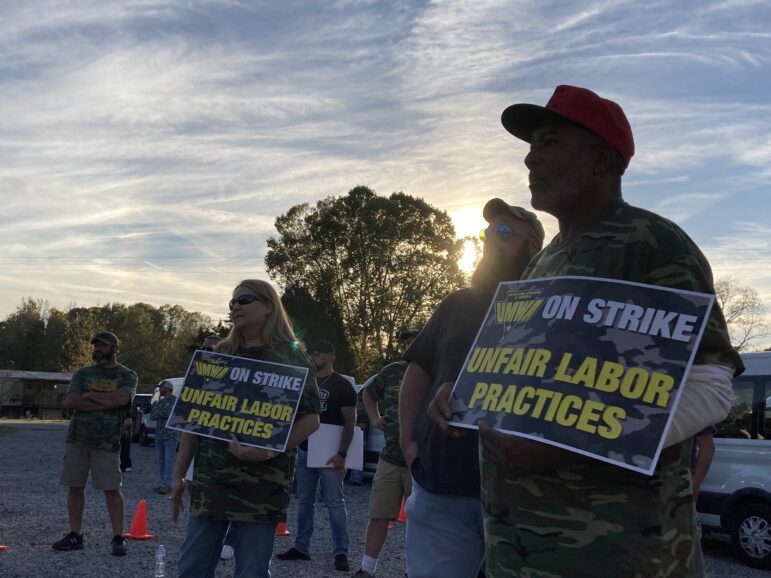

Hundreds of coal miners in Brookwood, Ala., reached a milestone Thursday: They’ve spent 20 months on strike.

That’s well past the six-week average for strikes, according to Bloomberg Law. The miners believe it’s the longest strike in Alabama’s history.

They have continued demanding their employer, Warrior Met Coal, restore the pay and benefits that were cut in 2016 as a cost-saving measure to keep the mines from shutting down.

Out of the 900 miners who started the strike a year and a half ago, 500 remain, according to United Mine Workers of America. And many of them say, despite missing their six-figure salaries, they’re doing just fine. They stick with a classic union catchphrase — they’ll last “one day longer” than the company.

Warrior Met has also remained resolute. With negotiations stagnant, the mines have kept operating and earning the company millions in profit.

Here’s how the miners — and the company — have survived the strike.

Strikers lean on a support system, an understanding of history and anger

If there’s one group of American workers used to labor battles, it’s miners. Consider the literal gunfights in the West Virginia mountains a century ago, or the 50,000 coal miners striking across 11 states during the Pittston Coal Strike of 1989. Consider too that coal is a feast-or-famine industry, and miners know the importance of saving up.

“Every old coal miner tells you that you prepare for the next day because you don’t know what to expect for that next day,” said Antwon McGhee, a striking Alabama coal miner.

Of course, many miners’ savings have dried up by now. That’s where having a strike-seasoned union, like the United Mine Workers of America in this case, helps.

The union knows it has to take care of those most vulnerable, said Kate Bronfenbrenner, director of Labor Education Research at Cornell University — like supporting a young miner with a mortgage and a new baby, or an older miner with health issues and higher medical bills.

“They work as a community to do that,” Bronfenbrenner said.

Every two weeks, the striking miners rally outside of a local union hall in Brookwood before shuffling inside to pick up $800 checks. Around the one-year mark, the United Mine Workers of America said it had given out $20 million to workers.

Union dues collected from miners across the country have been bolstered by donations from other unions and individuals. Together, they’ve built up a war chest that could enable the strikers to remain on the picket line for years, according to one local union leader.

“Strike checks is how I’m making it,” said Brian Kelly, Local 245 UMWA president. “There’s no doubt about it.”

Community stands behind the strikers, offering donations and jobs

Locals also are helping the miners out, whether by keeping the local food pantry stocked, providing backpacks for school or toys as Christmas approaches.

But perhaps the most helpful support has come in the form of side jobs. Thanks to the tight labor market, strikers have found work at nearby strip mines and a Mercedes plant. The money’s usually nothing close to what they made before the strike, but combined with the strike checks, it’s enough to cover at least some bills.

McGhee has taken on plumbing and home remodeling work for his friends and family. They could have hired professionals, he said, but wanted to make sure the check went to him. He said that matters more than the money.

“You can go out and make the money,” McGhee said. “But without that morale and mental support you can’t make it.”

Beyond that, the miners are also fueled by old-fashioned anger — at the strikebreakers crossing the picket line and at Warrior Met’s refusal to give them the pay and benefits they want.

“They’re holding out on us on purpose and not giving us the contract we deserve,” McGhee said of the company. “I think it’s evil. Purely evil.”

Warrior Met declined to comment for this story.

The anger has backfired at times. The National Labor Relations Board fined the union $13.3 million for damages, in part for violence on the picket line. The union challenged that amount, and the NLRB agreed to drop it to $435,000. During a recent rally, union president Cecil Roberts called for nonviolent civil disobedience.

Soaring steel costs have added to Warrior Met’s bottom line during the strike

The goal of a strike is to put pressure on an employer by hurting them where it counts — their bottom line. Enough financial pain from work stoppages will lead a company to giving into worker demands, the idea goes.

But not when the company’s enjoying record profits.

Warrior Met Coal reported nearly $100 million in net income between July and September — a significant jump from the same time last year. It estimated the strike had deflated its earnings by about $7 million during the same time – a dent to the company’s profits.

The metallurgical coal mined by the company isn’t used for energy, but to make steel. Even though steel prices have been declining, which many miners believe will force Warrior Met to negotiate, they remain high.

“The economy has been in their favor,” said Greg Freehling, a Michigan State University adjunct professor who used to be the director of labor relations for the aluminum maker Arconic. “Anytime the company’s in a position where they’re making money…it gets a little bit easier to weather these sorts of things.”

Warrior Met fills jobs with out-of-state workers and strike breakers

The high price of steel right now wouldn’t mean much if Warrior Met couldn’t find workers to extract that coal.

Some miners have crossed the picket line, simply because giving up a six-figure salary for more than a year-and-a-half is tough. And miners from West Virginia and Pennsylvania volunteering for the union said they’ve seen Warrior Met recruiting workers in their states, which have plenty of former coal miners thanks to the decline of coal jobs across the country.

Freehling said the fact the company has been able to operate for so long with its current workers is a bad sign for the union – and a clear sign that the stalemate will last well beyond 20 months.

9(MDA2ODEyMDA3MDEyOTUxNTAzNTI4NWJlNw004))

When a horse whinnies, there’s more than meets the ear

A new study finds that horse whinnies are made of both a high and a low frequency, generated by different parts of the vocal tract. The two-tone sound may help horses convey more complex information.

Trump’s many tariff tools mean consumer prices won’t go down, analysts say

The Supreme Court struck down President Trump's signature tariffs. But the president has other tariff tools, and consumers shouldn't expect cheaper prices anytime soon, economists say.

Hundreds of American nurses choose Canada over the U.S. under Trump

More than 1,000 American nurses have successfully applied for licensure in British Columbia since April, a massive increase over prior years.

Tax credits for solar panels are available, but the catch is you can’t own them

Rooftop solar installers are steering customers toward leases instead of purchases. Federal tax credits for purchased systems have ended but are still available for leased ones.

5 takeaways from Trump’s State of the Union address

President Trump hit familiar notes on immigration and culture in his speech Tuesday night, but he largely underplayed the economic problems that voters say they are most concerned about.

China restricts exports to 40 Japanese entities with ties to military

China on Tuesday restricted exports to 40 Japanese entities it says are contributing to Japan's "remilitarization," in the latest escalation of tensions with Tokyo.