After launching in Atlanta, rural Georgia is the next stop for this guaranteed income pilot

A mural featuring actress Liddie Murphy is seen in downtown Cuthbert’s Magnolia Alley Market, June 22, 2022. The mural, which highlights famous local residents, also features musician Fletcher Hamilton Henderson.

By Aubri Juhasz/WWNO, Stephan Bisaha/Gulf States Newsroom

Tanika Acosta stands outside a Dollar General in Cuthbert, Georgia trying to get shoppers to sign up for what is, essentially, free money.

Often, the women Acosta approaches are skeptical of a stranger holding a flier, but their reaction tends to change after she gives them her pitch.

“$850 a month, no strings attached, though, ma’am. Can I explain that to you?” Acosta says running through her script. “That kind of makes them say, ‘OK, what you talking about?’”

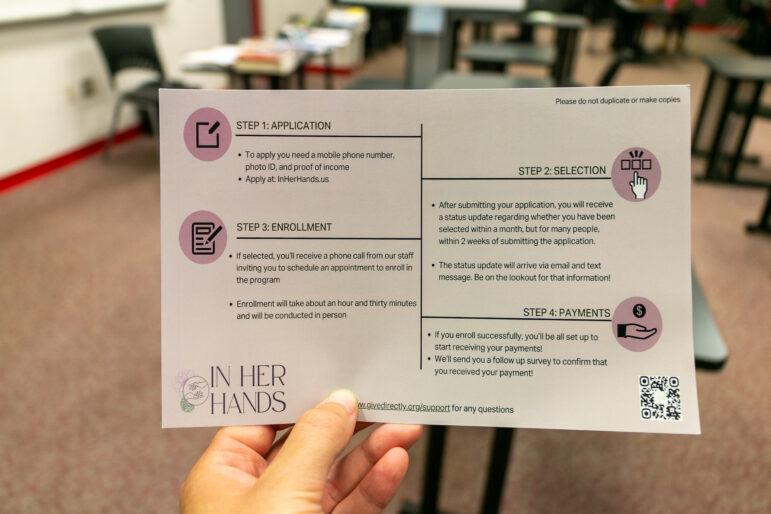

What Acosta is talking about is called In Her Hands, a $13 million guaranteed income initiative for Georgia women funded by private donors and run by two nonprofits — the GRO Fund and GiveDirectly.

Guaranteed income programs are becoming increasingly common across the U.S. — largely due to progressive, big-city mayors who see cash payments as a way to help their residents directly.

While In Her Hands started giving out money to women in Atlanta’s historic Old Fourth Ward first, the program also has plans for a rural and a suburban pilot. Across the three sites, approximately 650 women are expected to receive an average of $850 a month for two years.

With the Atlanta pilot underway, the program is now focused on getting its rural program up and running. That’s why Acosta was in Cuthbert, in Randolph County, nearly two-and-a-half hours south of Atlanta, in late June. With the application deadline four days away, Acosta urged a woman in the Dollar General parking lot to apply right away and get the word out.

“I say get it in right now and make sure that you tell everyone,” Acosta said. “Tell your niece, tell your sister, tell your cousins.”

Reaching rural applicants

Cuthbert is a majority-Black town with fewer than 4,000 residents, many of them retirees. In its downtown district, there’s a quaint town square with a towering, Confederate monument at the center of it. Roughly a dozen businesses flank the square: there’s Hixon Hardware, a thrift store called This & That and a hotdog spot named the Dawg House.

Cuthbert is in the Black Belt, a region historically known for its rich black soil — though in Georgia the soil is typically red — and plantation economy. Today, the region suffers from a lack of industry and population decline, with each factor influencing the other.

In Her Hands is enrolling residents in three neighboring counties; Clay, Terrell and Randolph. All three counties have a majority-Black population and the poverty rate of each is at least 30% — more than double Georgia’s overall rate. To qualify, applicants need to make less than 200% of the federal poverty line. For a family of four, that threshold is roughly $56,000 a year.

The program isn’t exclusively for women of a particular race, but deputy director Renee Peterkin said the program has deliberately focused its outreach on Black women as a way to address pay inequality and high rates of economic insecurity.

A core value of the program is making sure the women who apply are treated with dignity. Peterkin said the approach is meant to counter traditional welfare programs with invasive and punitive policies.

“I don’t think asking for help should leave you feeling demoralized. It’s what keeps us from asking for more help,” Peterkin said. “I don’t think there’s anything wrong with needing some help.”

With that in mind, the In Her Hands application is fairly minimal compared to the level of questioning many welfare recipients are used to. The only documents applicants have to submit through the online application are photos of their ID and a document proving their income eligibility.

Victoria Bowden, In Her Hands’ engagement manager, said the program also made changes to the application based on community feedback to help build a sense of trust between program organizers and residents. Bowden and others spent weeks meeting with residents through listening sessions, forming and working with a local advisory council and canvassing — all with the goal of ensuring the program was accessible and suited the community’s needs.

For example, the online application has a voiceover feature so applicants who can’t read the tiny, on-screen text can listen instead. The application’s address subfield also pulls from United States Postal Services data, instead of just found Google Maps addresses, since the latter doesn’t always have complete records for rural areas.

But while the application has a relatively low barrier to entry, completing it can still be challenging, especially for older residents, since the application is online and requires them to enter a confirmation code sent by text message. To address that, Bowden and others held several days’ worth of office hours at locations across the three counties.

Bowden said women in the region have also played a key role in getting the word out about the program.

“Even before we even had fliers, they were like, ‘As soon as the application opens, we have all these people who [want to sign up],” Bowden said. “I wasn’t worried at all that the word would spread.”

Once the application opened on June 6, Bowden said they hit their 1,000 application goal within a few days and doubled it within a few weeks.

“We’re gonna need everything we can get”

On a hot June afternoon, Bowden and Peterkin rearranged tables inside a classroom at a local technical college and put on some music. Over the course of a few hours roughly a dozen, largely older, women trickled in looking for help.

Everene Evans walked in wearing a bright orange dress and wide-brimmed sun hat.

“I’m trying to keep cool,” the 78-year-old said cheerfully.

When she first heard of the program from a staff member standing outside of the local Piggly Wiggly, she was shocked by the amount: $850 a month. That’s $20,000 over the course of two years.

Rural residents tend to have access to far fewer resources from both government and nonprofits. Often, the only support they receive is from long-standing federal benefit programs like food stamps and disability, which often don’t provide enough money for people to live comfortably.

Evans said her only source of income is her social security check. If selected for the pilot, she already has a plan for the money — saving it.

“Really I would, for hard times. Because in this day and time we’re gonna need everything we can get,” she said.

To some extent, hard times have already arrived. Many people living in this part of Georgia are on fixed incomes, which makes them particularly vulnerable to the recent rising costs from inflation. Evans said she’s felt it personally.

“The gas tank … the food and then you go in the store now and some shelves are empty,” she said.

Addressing the benefits cliff

Bowden said many of the women she’s spoken to in Atlanta and in rural Georgia are afraid the new income could cause them to lose their pre-existing benefits. Many are painfully aware of what’s known as benefits cliffs.

The amount of assistance programs like SNAP, best known as food stamps, provide is based largely on income. That means any income increase — either from a raise or a guaranteed income program — can lead to a sharp drop in benefits. This change can leave a person getting benefits worse off than they were before.

Some guaranteed income programs have attempted to secure waivers from state and local agencies to freeze participants’ pre-existing benefits. But in Republican-controlled states organizers doubt this type of political maneuvering can be successful.

This is a worry for Betty Starling, 61, a former certified nursing assistant. Starling had a stroke in 2010 and her sole source of income is her monthly $1,100 social security disability check.

She said the $850 a month would be incredible, but not if she lost her disability check. If she’s selected for the pilot, she’s not sure if she’ll accept.

“We need extra money to help, to survive,” Starling said.

Starling said she had to hire a lawyer to prove to the state that she was eligible for disability. If she loses the benefit, even just temporarily, she doesn’t want to have to go through that process again.

Bowden assured Starling that applying for the program wouldn’t jeopardize any benefits she receives and that if selected she’ll be able to sit down with a counselor who can walk her through a cost-benefit analysis.

‘[I] pray to God I get it’

Shirley Fillingham, 75, is a retired teacher who worked with special needs students in the local public school district for 35 years and later returned as a substitute “because they needed me.”

Fillingham, a two-time cancer survivor, has a low, gravelly voice and thinning hair. She misses working but bakes pies, colors and crochets to keep busy.

Her sole source of income, like Evans, is her social security check. Fillingham said she’s “blessed” with her children, but tries not to worry them.

“They know I’m going through some things financially when it comes to my medical bills, medicine and stuff like that,” she said. “They would love to hear that I get this here money. They’d be like, ‘Go Ma!’ [I] pray to God I get it.”

The application for In Her Hands’ rural pilot closed in late June and program leaders will be calling selected participants in the coming weeks. Out of more than 2,000 applications, 230 women will be selected by lottery.

If selected, Fillingham said she’d call her children right away to tell them the good news.

“I’d say, ‘Guess what? I’ve been blessed.’” Fillingham said. “That’s what I would tell them.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration among Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama and WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

U.S. has a quarter fewer immigration judges than it did a year ago. Here’s why

The continued drain of personnel from the already strained immigration court system has contributed to depleted staff morale, mounting case backlogs — and floundering due process.

Poll: Most say the state of the union is not strong and the U.S. is worse off

Ahead of the State of the Union address on Tuesday, evidence continues to mount that President Trump is facing political headwinds.

The owners want to close this Colorado coal plant. The Trump administration says no

The Trump administration has ordered several coal plants to keep operating past their planned retirement, part of a larger effort to boost the coal industry. Two Colorado utilities are pushing back.

Influencers are promoting peptides for better health. What’s the science say?

The latest wellness craze involves injecting these molecules for athletic performance, longevity and more. Scientists say the research isn't keeping pace with the health claims.

Mexico fears more violence after army kills leader of powerful Jalisco cartel

School was canceled in several Mexican states and local and foreign governments alike warned their citizens to stay inside following the army's killing of the leader of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, Nemesio Rubén Oseguera Cervantes, "El Mencho," and the violence it spurred

Newly discovered dinosaur species was a fish-eater with a huge horn

The semi-aquatic dinosaur, Spinosaurus mirabilis, was discovered by an international team of scientists working in Niger.