A year into striking, Alabama coal miners are frustrated but defiant as ever

Striking coal miners pick up their strike checks from the United Mine Workers of America at a union hall on March 23, 2022, in Brookwood, Alabama.

Coal mines are, unsurprisingly, a tough place to work. They’re dark and dirty and every breath brings in toxic chemicals.

And Brian Kelly wants to be back there.

“I love it,” Kelly said. “It’s paradise to me.”

Kelly fell in love with the mines because of the brotherhood he forged 2,000 feet underground. Over the last year, that bond has been tested. Friday marks one year since Kelly and 900 other coal miners went on strike in Brookwood, Alabama.

The strikers demand that Warrior Met Coal, the company they’re striking against, restore the pay and benefits miners gave up in 2016 when the mines were in danger of shutting down.

As the months crawled on, the miners stuck with a slogan — “one day longer.” As in, they’re willing to hold out on this strike one day longer than Warrior Met Coal will. But a year without their old paychecks has caused a few workers to cross the picket line. The hundreds that remain still defiantly say “one day longer,” though they admit that it requires deep sacrifice and it’s building resentment.

‘Them pennies come in handy when you’re pinching them’

Before the strike, Rily Hughlett made $103,000 as a roof bolter — making sure the recently carved rock above the miners’ helmets didn’t cave in.

But Hughlett knows how quickly that paycheck can disappear. A pocket of hazardous gas could shut down a mine for months. Miners who are injured can be forced to remain above ground until they heal. A rock the size of his living room once fell and grazed his leg — enough to lead to a knee replacement and six months off the job.

Those experiences taught Hughlett how important it is to save — and those habits paid off when it came time to strike.

“I save every penny I could save,” Hughlett said. “Them pennies come in handy when you’re pinching them.”

Dipping into their savings hasn’t been enough for most miners to get by, though, forcing them to take other jobs. Some are at the Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, a 30-minute drive east of the mines. Hughlett is working at a strip mine running a drill rig — which he calls a pretty good gig. He likes getting to spend his day in an air-conditioned cab, compared to the hot underground mines he’s used to.

But the pay falls short. He wants back in the Warrior Met Coal mines, but refuses to cross the picket line, both for personal pride and loyalty to his colleagues.

“I, myself, couldn’t look someone I worked with for five years in the eye … and say ‘well, I just give up,’” Hughlett said.

Strike not just about money, but dignity

Hughlett and the other miners on strike say their demands aren’t just about money, but dignity. They made sacrifices to keep these mines open and now they say the company is failing to hold up its end of the deal.

Walter Energy, which owned the mines in 2015, went bankrupt when the price of steel made from the coal extracted from Brookwood plummeted. Warrior Met Coal formed as a new company in the aftermath and took over running the mines in 2016.

Warrior Met Coal told the workers that keeping the mines open would require cuts, like fewer days off and lower pay. Hughlett said his salary was cut by $17,000.

But miners accepted the terms with the understanding that the company would consider restoring the lost pay in five years. Since then, the price of steel has shot back up, but Warrior Met has not offered to bring back the old salaries and benefits.

“They come out of bankruptcy, you know, head shining like a star. They’re making their money back,” Hughlett said. “That’s when [they] stuck [their] finger in our face.”

That led the United Mine Workers of America, the union which represents the Warrior Met miners, to declare a strike on April 1, 2021.

Hughlett admits he’s been surprised by the support from the union. Beyond his savings and the new job, what’s really helped him get by are the checks the union provides every other week. Those checks come from a strike fund — a pool of union dues from miners across the country.

The union reports that it has handed out about $20 million to the miners and has enough funds to keep the checks coming for years.

Between that and donations from labor supporters and other unions, Hughlett has been getting about $2,000 a month — just a quarter of what he made before the strike. But, it makes a big difference.

“I’ll give it to the UMWA – they have stepped up more than I suspected,” Hughlett said.

‘In whatever manner you need to’

To keep the mines running, Warrior Met Coal has hired workers from places like West Virginia. The union accused those workers of ramming people on the picket line with vehicles. Warrior Met Coal has blamed the strikers for causing violence.

In October, a Tuscaloosa County Circuit Court judge issued a restraining order preventing the miners from picketing outside the mine entrances. The lines have since been allowed back, but with limits – picketers can’t park vehicles near the entrance.

At a union rally in March, local organizer Larry Spencer told the crowd to approach people still working at the mines and help them leave “in whatever manner you need to.” He told a story about confronting one such worker in Northport, 25 miles from Brookwood.

“He said ‘What are you going to do?’” Spencer said. “I said ‘I’m going to beat your eyes out and blow your brains out. That’s what I’m going to do because I’m tired of you taking my brothers’ and sisters’ jobs.’”

For Kelly, seeing people he spent years working underground with crossing the line is more painful than watching new workers coming in from the north.

The union believes about 15% of those who were striking went back to work at the mine.

At 18, Kelly went with his father to picket during the Pittston Coal strike in 1989. He was taught to pay off his house as soon as he could and skip out on the $70,000 truck so he’d be prepared when it was his turn to be on strike.

He suspects many of the younger miners that have since crossed the line didn’t have family ties to coal. They also likely didn’t take his advice to save their money in preparation for a strike.

“One by one, the ones who I really thought I reached out to crossed the picket line,” Kelly said. “It hurt. It really hurt.”

Rallies boost spirits as the conflict drags

The union’s weekly rallies for the miners used to be held at the Tannehill Ironworks Historical State Park. The rallies had a southern barbecue atmosphere, with plenty of laughs and hotdogs on the grill.

Then, they moved to Brookwood’s ballpark when the baseball season ended. But the strike has gone on long enough that a new season of baseball has started and the rallies are now held at a local union hall. A year in, the party mood has been replaced with one more somber, but the camaraderie remains.

After a closing prayer at a recent rally on March 23, the miners shuffled into the hall to grab meals in styrofoam containers and line up for their union checks. Todd Burkes was there to pick up his check and some for other miners who couldn’t make it while they worked elsewhere.

To get by, Burkes is operating a forklift at the nearby Mercedes-Benz plant in Vance, Alabama. Similar to Hughlett, he likes the job, just not the pay. Losing a six-figure salary requires a whole new lifestyle — no more vacations, no going out.

“It’s going to take a year to get your life back together,” Burkes said.

Despite the smaller crowd, coming to these weekly rallies gives Johnny Murphy a needed boost to his spirit. He worked for Warrior Met Coal as an underground motorman, a dangerous job transporting heavy equipment across the mines.

Now, he’s temporarily working at U.S. Steel, but the constant rotation between working days and nights has messed with his blood pressure. Financially, he believes he’s got another month or two before he seriously needs to think about how he can support his family.

“We’re on the verge of just probably being in trouble,” Murphy said.

Murphy also repeats the “one day longer” line and vows never to cross the picket line. His dad was a coal miner who would “probably beat the hell” out of him for crossing because there’s no excuse for breaking a strike.

The tension can even be felt across the small handful of Brookwood restaurants. One miner suggests skipping over Henry’s Burgers and Cream and, instead, eating at La Casa Crimson on the opposite side of the ballpark. The reason? La Casa Crimson supports the strike; the miner said Henry’s Burgers and Cream does not.

A bit before noon at Henry’s, one coal miner sat alone waiting for his food. Soot covers his hands, reflective vest, young face and long brown hair.

He says he stuck with the strike at first. But as the months went on, he couldn’t afford to not go back to the mines. He declined to give his name.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration among Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama and WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

These major issues have brought together Democrats and Republicans in states

Across the country, Republicans and Democrats have found bipartisan agreement on regulating artificial intelligence and data centers. But it's not just big tech aligning the two parties.

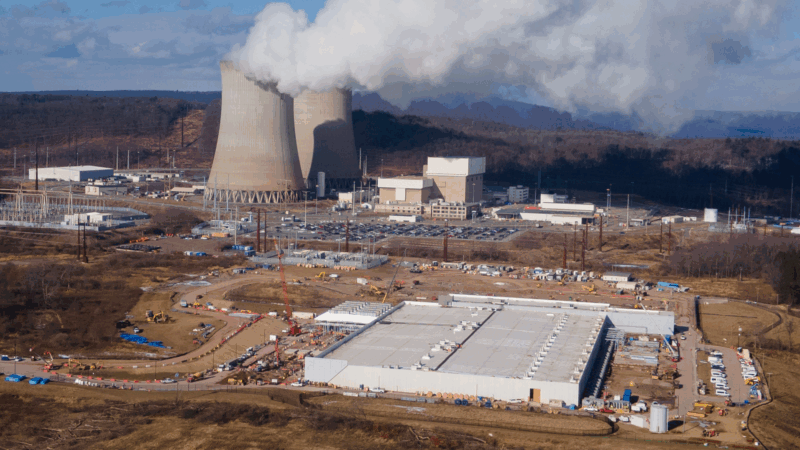

Feds announce $4.1 billion loan for electric power expansion in Alabama

Federal energy officials said the loan will save customers money as the companies undertake a huge expansion driven by demand from computer data centers.

Mortgage rates fall below 6% for the first time in years

The average home loan rate has dropped below 6% for the first time since 2022. Will that help thaw the frozen housing market?

Baby Keem’s boulevard of broken dreams

Ca$ino, the rapper's second album for his cousin Kendrick Lamar's label, is whiplash embodied, a mirror for the extreme highs and lows of his Sin City hometown.

Pentagon shifts toward maintaining ties to Scouting

Months after NPR reported on the Pentagon's efforts to sever ties with Scouting America, efforts to maintain the partnership have new momentum

Why farmers in California are backing a giant solar farm

Many farmers have had to fallow land as a state law comes into effect limiting their access to water. There's now a push to develop some of that land… into solar farms.