Using Pastors And Pints, Gulf States Try To Boost COVID Vaccination Rates In White Communities

Virginia Faulkner, 64, and her husband dealt with major health issues last year and waited until this month to go out in public and get their shots at Meadowood Baptist Church.

On the edge of rural northeast Mississippi, only a third of the 37,000 residents in predominately white Monroe County have been vaccinated so far. This trend falls in line with national polls showing that rural white communities are among the most vaccine-hesitant groups in the country.

In Amory, Miss., a small town in the county with a population of less than 7,000, Meadowood Baptist Church and Access Family Health, a community health center, teamed up last week to try and raise those numbers.

Worship music played throughout the church’s gym to ease anxieties. Casey Powell, 41, Meadowood’s youth minister, was one of the 30 people who got their shots.

“[It’s] the unknown … something we never really experienced at this stage of life,” said Powell, who doesn’t remember getting vaccinated as a kid.

Data from the Kaiser Family Foundation show that Mississippi, alongside Louisiana and Alabama, have the lowest vaccination rates nationally – at or below around 42%. The national average is 55%.

“We’re a big rural state,” said Scott Harris, health officer for the Alabama Department of Public Health. “There are some people who just haven’t been able to get it yet.”

But Harris acknowledges that hesitancy, not just access, is a big factor in the South.

“The hesitancy we’ve seen in African-American communities is different from the hesitancy we’ve seen in rural white communities,” he said.

Shalina Chatlani,Gulf States Newsroom

Lloyd Sweat, left, pastor at the Meadowood Baptist Church eases youth minister Casey Powell’s anxieties about getting his coronavirus vaccine.

Public health data from Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama show white residents have lower vaccination rates than Black residents. In particular, national polls showed conservative white men are some of the most hesitant in the nation to take the coronavirus vaccine.

“I did 10 years in the military, and I was pretty much a guinea pig,” said Brandon Aday, 33, a white resident of Amory, Miss. “You get told to go here, go there, and you just get needles on your arm.”

Aday said there’s a common sentiment in the South: “I’m American, I can do what I want, and you ain’t going to take my guns.”

For him, having a choice is most important.

“It’s my body, and until I see significant research, significant anything, why take the risk?” Aday said.

Columbus resident, John Holliman, 73, said he got COVID-19 in December and decided to get his first dose of Moderna as soon as he could in January. But he said he got sick from the shot.

“I just ached and hurt all over, and my chest felt like you’d knocked a hole in it and it was on fire,” Holliman said.

He doesn’t plan on getting his second shot.

State health officials are pivoting to address these types of concerns. At the beginning of the vaccine rollout, Mississippi focused on reaching as many people as possible using drive-thru sites in metropolitan areas. But, as demand has slowed to a crawl, the main strategy now is to encourage local leaders, like pastors, to deliver the message that it’s safe and effective.

Shalina Chatlani,Gulf States Newsroom

A sign outside a vaccination event in Meadowood Baptist Church in Amory, Miss.

Lloyd Sweat, pastor at Meadowood Baptist Church, has been doing just that and stopped by to see some of his church members at the vaccination event.

“I’ve shared that I’ve done it and some have said, ‘OK, I’ll do it then,’ ” said Sweat. “I guess if I had said I’m never going to get it, it probably would have affected things in an adverse way. But I didn’t have any reservations about it.”

Sweat reminded some of his church members that they may need to get the COVID-19 shot in order to go abroad for mission trips. That was an effective incentive for some, he said.

In Louisiana, other Christian groups have come under scrutiny for telling their followers to not get vaccinated. For Sweat, vaccination looks like the best way for churches to fully open safely for services again.

“The church has been a place where we can do the vaccine and open their doors to anybody that wants to come. Most in the South still have some degree of trust in the church,” Sweat said.

Shalina Chatlani,Gulf States Newsroom

Empty tables and chairs fill the gym of the Meadowood Baptist Church in Amory, Mississippi. The church held a vaccination event with a local community health center, and 30 people trickled through the event to get their vaccines.

But, even with help from the church, it’s not easy to get everyone on board. Thomas LaVeist, health policy and equity expert at Tulane University, thinks a combination of carrots and sticks would work best in the Gulf States.

“I would love to see the CDC loosen its guidelines a bit more for people that have been vaccinated,” said LaVeist. “So one carrot is more freedom for people that have been vaccinated.”

Some cities across the South have already been dangling incentives – a pound of free crawfish in New Orleans or the possibility of free beer in Birmingham.

LaVeist, who’s on Louisiana’s COVID-19 equity task-force, wants policymakers to be sensitive to concerns about individual liberty, but he notes that vaccination rates for shots given in childhood, like those for measles and mumps, are above 90% in the Gulf States.

Those are mandatory in public school and in some other settings. But states are unlikely to add COVID-19 shots to their mandatory lists until the vaccines move past the current emergency use authorization to full approval.

Shalina Chatlani,Gulf States Newsroom

John Holliman, far right, stopped at Bill’s Burgers in downtown Amory, Miss., for lunch said he got his first Moderna shot, but said it “nearly killed him.” He’s decided not to get his second shot.

“The reason that we’re not treating COVID like any other virus, like we treat smallpox, is that it became politicized,” LaVeist said.

He is hopeful that the number of schools and employers requiring COVID-19 vaccinations will grow, and that will help pull up numbers in the South.

Now that Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advisers have recommended administering the vaccine to adolescents aged 12 to 15, pediatricians will also play an important role in convincing parents to vaccinate their kids.

“This is a real challenge,” he said. “And we don’t really have much of a road map to go by.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between WBHM in Birmingham, Alabama, Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WWNO in New Orleans and NPR.

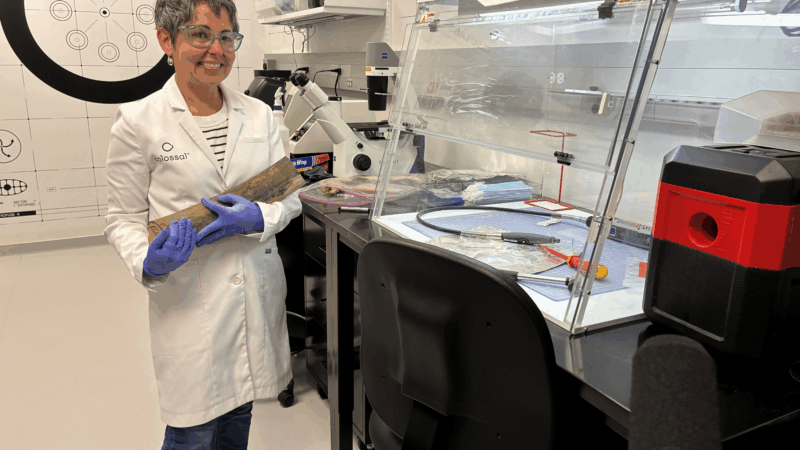

Colossal Biosciences breeds controversy while trying to revive mammoths

A Texas biotech company is trying to bring mammoths and other extinct creatures back to life. The science is as intriguing as the ethical questions are thorny.

Mundane, magic, maybe both — a new book explores ‘The Writer’s Room’

Why are we captivated by the spaces where where authors write? Katie da Cunha Lewin set out to explore "The Hidden Worlds That Shape the Books We Love."

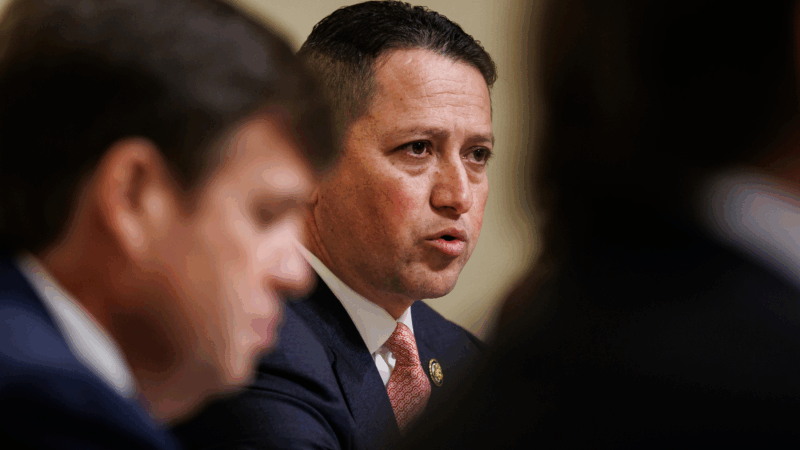

GOP Rep. Tony Gonzales heads to a runoff in Texas amid a new ethics probe in the House

Texas Republican Rep. Tony Gonzales has faced increasing pressure from his party to resign or drop out of his race after allegations of an affair with a staffer.

Satellite images show Iran school strike hit more targets than earlier reported

The images suggest that precision munitions struck other buildings, including a clinic that was also inside the complex.

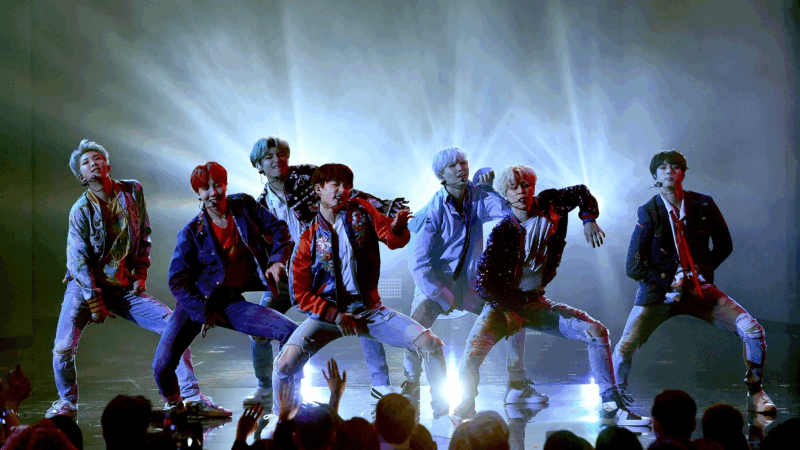

As live music becomes more inaccessible, most fans stay watching through screens

Now that it is becoming harder and harder to get a ticket to your favorite artist's show, watching indirectly is becoming a popular compromise. What is gained and lost in a tiered concert hierarchy?

Paul McCartney’s decade of transformation: From Beatles breakup to John Lennon’s murder

Man on the Run shows McCartney's effort to define himself outside The Beatles' shadow: "Paul making this documentary was a way of coming to terms with that whole period," says director Morgan Neville.