Written in Black and White: In Alabama’s Statehouse, the Parties Are Split Almost Entirely by Race

By Mary Sell

When newly elected Neil Rafferty takes his place in the Alabama House of Representatives next year, he will be the only white Democrat in the 105-seat chamber

With one other white Democrat in the Senate, the Alabama Legislature’s two parties are almost entirely divided by race. An all-white GOP has a supermajority.

“You can’t deny the optics at times,” Rep. Chris England, D-Tuscaloosa, said about the party and racial split. He’s been a lawmaker since 2006 and has seen the racial polarization increase as the white Democrats dwindled in numbers.

Less than 10 years ago, in the 2006-2010 term, there were 62 Democrats in the House. More than half of them were white, said House public information officer Clay Redden. Now, there are 28 Democrats total. Republicans picked up five more seats in last week’s election.

In all, more than 75 percent of the members of the Legislature were white less than a decade ago, and more than 60 percent were Democrats, according to an analysis done at the time by The Birmingham News.

Being the minority race in the minority party isn’t something Rafferty, D-Birmingham, said he’s thought too much about.

“I’m going to go down there with humility and an eagerness and willingness to work with my colleagues, all of my colleagues, for the betterment of the state and House District 54,” he said last week.

But race has been an issue in the Statehouse in recent years.

England is concerned that, without diversity among parties, all issues begin to be viewed in a racial context.

“Racial issues are important, they are, but not everything is racial,” he said. “You don’t want everything to be painted with a broad brush because of the messenger and lose the message.”

For example, Medicaid expansion would benefit thousands of white Alabamians, but if the almost entirely black Democrats are the only ones advocating for it in the Statehouse, it looks like a racial issue, he said.

D’Linell Finley, a pastor and political science professor at Alabama State University, said there is an obvious answer to the Statehouse split.

“In Alabama, we don’t want to admit it, but in 2018 race is still a decisive factor in how people vote,” he said.

He also credits the national GOP in recent years for creating an agenda that’s attractive to many white voters.

“It has projected itself as at the pro-family party,” Finley said. “It seems to have successfully taken the higher ground on the morality issues.”

Alabama is a very conservative state and the GOP has made issues of same sex marriage and transgender rights and immigration.

“These things appeal to the conservative voter and the conservative voter in this state happens to be white at this time,” Finley said.

Before last Tuesday, there were six white Democrats in the Alabama House. Five didn’t seek re-election and one, Elaine Beech, was defeated. Rafferty won by a large percentage the seat previously held by another white Democrat, Patricia Todd.

Things Have Changed

Todd said she plans to meet with Rafferty soon and offer some advice, but she said he’s walking into a different situation than she did in 2006.

“That’s not good,” she said about the split. “Diversity of opinion of race and gender always make for better government, in my opinion.”

The GOP added two more women to its roster of representatives last week.

“(Rafferty) has to figure out how to be most effective and it’s tough when you’re a minority of a minority of a minority,” Todd said. Rafferty is gay, as is Todd.

“Neil has to figure out his way but being a former Marine, he’s used to working with a lot of diverse groups,” Todd said.

In the 35-seat Senate, Billy Beasley of Clayton has been the lone white Democrat since 2014. Beasley did not return calls for comment.

In all, Republicans gained one seat in the Alabama Senate and five in the House.

“It’s going to be a tough road for Democrats and, in reality, they have to figure out how to make themselves part of the conversation,” Todd said. “My experience is the Republicans don’t bring us to the table,” she said. “They’re not interested in bipartisanship.”

Speaker of the House Mac McCutcheon, R-Monrovia, last week said he’s not concerned about the racial makeup of the chamber.

“I feel like my challenge as speaker is to try to bring together the body as a whole and get legislators to work together,” he said.

But that has been a challenge at times and race has been a factor.

In the 2016 session, black members of the House stood on the chamber floor and sang, “We Shall Overcome” after Republicans used procedural rules to end debate and pass a bill that would have forced a Huntsville abortion clinic to move.

The end of the 2017 legislative session was also divisive. Bills to redraw several House districts after Republicans “packed and stacked” them with minority voters in 2012 and to protect Confederate monuments lead to anger and filibusters by the black caucus. They also were angry about an email sent by a white representative that compared legislators to monkeys in a cage fighting over a banana. Those delays ate up several legislative days in the House and led McCutcheon to call for diversity training for representatives.

Last week, McCutcheon said that training will be mandatory before the start of the 2019 session.

Meanwhile, lawmakers have some heavy lifting in front of them. McCutcheon said he expects “a good debate” on a possible statewide lottery and an infrastructure bill that will include a gas tax increase.

“Just because we have a super, supermajority in the House, I’m not going to run over the minority in the House,” McCutcheon said. “I want to hear them and address issues of the state.”

Minority Leader Rep. Anthony Daniels, D-Huntsville, said he looks forward to working with Rafferty, particularly on healthcare, and other new Democrats.

“We’ve got some really bright people replacing some experienced legislators,” Daniels said.

There are now 28 Democrats in the Alabama House and Daniels said they’re working to not just play defense against GOP initiatives.

“I expect us to be moving at a fast pace,” Daniels said of the upcoming term. “We can speed up our offense.”

Political Drift

Outgoing Rep. Marcel Black, D-Tuscumbia, left the Alabama House this year after serving 28 years. Black describes himself as a moderate.

“But a moderate Democrat in the Alabama Legislature is a raging liberal,” he said.

Over the years, he’s watched his Democratic colleagues drift away, switch parties and get defeated.

There are several Republican lawmakers in the Statehouse who were once Democrats and who say their politics didn’t change — they were always conservative — but the parties changed.

Wayne Flynt, an Alabama historian and author, said that’s probably true.

“I think it’s important to note the Democrat Party has gone to the left, just like the Republican Party has gone to the right,” Flynt said.

He adds: “There is also a lot of opportunism in politics.”

Daniels said Democratic turnout was up last week compared to previous elections. But some Democratic candidates couldn’t compete with two amendments geared toward conservative voters. One allowed the display of the Ten Commandments on public ground and the other was pro-life.

The demise of and lack of support for Democratic candidates by the state party has also been cited in the past week as at least part of the problem. Straight party voting also played a role. About 65 percent of people who voted last week cast straight party tickets, more of them Republican than Democratic.

Not Just Alabama

In 2010, Alabama Republicans launched a successful, coordinated and expensive effort to take over the Statehouse from Democrats. Not only was that battle a success, Republicans won all statewide offices in Alabama that year.

It was part of a national Republican push to gain control in state offices. In 2012, the GOP won the Arkansas Legislature, and the Republican takeover of state legislatures in the once solid Democratic South was complete, according to an article by the National Conference of State Legislatures.

The shift was decades in the making, experts have said in recent years, and a result of multiple factors, including race, religion and economics.

But race is one of the bigger factors.

Flynt said politics have become racially polarized.

“What we now have is a battle that’s not just about politics but about culture,” he said.

Political science professor Jess Brown has said whites started leaving the Democratic Party when it stopped promoting segregation and instead began campaign against it. Republicans, meanwhile, started campaigning in the 1980s on issues such as school prayer and pro-life stances, attracting conservative Christians.

When Ronald Reagan was elected in 1980, 40 percent of white voters identified as conservatives, the National Conference of State Legislatures reported. By 1988, that percentage had jumped to 60. Republican ranks increased by 50 percent in the 1980s, many white moderates among them.

In Alabama, like other Southern states, the party switch started in federal offices, then statewide offices.

Since 1956, Alabamians have voted for only one Democratic presidential candidate, Jimmy Carter in 1976.

Outside of U.S. Sen. Doug Jones, Alabama hasn’t had a statewide elected Democrat since 2012.

Jones won the Senate seat in a special election last year, but his campaign was helped significantly by Republican Roy Moore’s lack of support from his own party after allegations of sexual misconduct decades earlier.

Improvise, Adapt, Overcome

Rafferty approaches his tenure as the lone white Democrat in the House with an unofficial Marine motto in mind: Improvise, adapt and overcome.

He’s already starting out as not the textbook Alabama Democrat.

A program director at Birmingham AIDS Outreach, Rafferty describes himself as progressive and ran on a platform that included advocating for responsible gun ownership to combat gun violence, reducing reliance on fossil fuels and expanding Medicaid. He’s also pro-choice.

“I entered the race to continue my life of service and to fight along with the people I’ve been serving this entire time,” Rafferty said.

Rafferty describes his politics as progressive, but also pragmatic.

“Even (if) we can’t expand Medicaid, I still think there are things we can do to improve health care and delivery in this state,” he said.

The new legislative session begins in March.

Prediction market trader ‘Magamyman’ made $553,000 on death of Iran’s supreme leader

It's the latest trade drawing scrutiny on the popular prediction market site for appearing to show an insider making profits on military secrets.

Oil prices rise sharply in market trading after attacks in Middle East disrupt supply

The high prices came as U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iran and retaliatory strikes against Israel and U.S. military installations around the Gulf sent disruptions through the global energy supply chain.

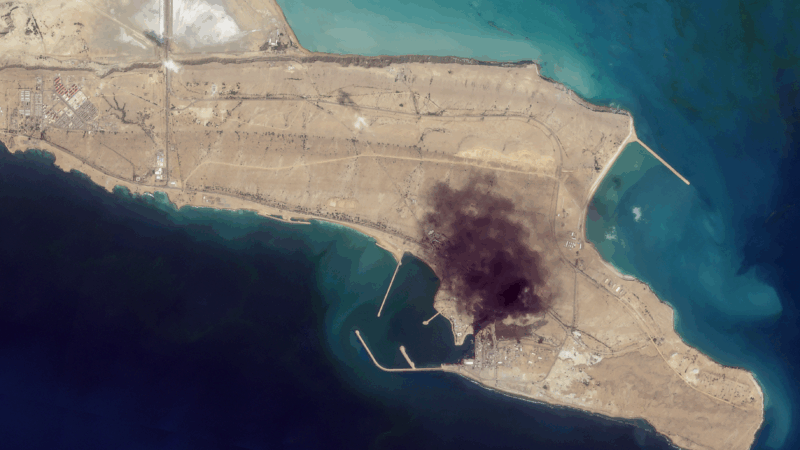

Satellite images provide view inside Iran at war

Satellite images from commercial companies show the extent of U.S. and Israeli strikes, and how Iran is responding.

Mideast clashes breach Olympic truce as athletes gather for Winter Paralympic Games

Fighting intensified in the Middle East during the Olympic truce, in effect through March 15. Flights are being disrupted as athletes and families converge on Italy for the Winter Paralympics.

A U.S. scholarship thrills a teacher in India. Then came the soul-crushing questions

She was thrilled to become the first teacher from a government-sponsored school in India to get a Fulbright exchange award to learn from U.S. schools. People asked two questions that clouded her joy.

Sunday Puzzle: Sandwiched

NPR's Ayesha Rascoe plays the puzzle with WXXI listener Jonathan Black and Weekend Edition Puzzlemaster Will Shortz.