High School Students Track Real Cybercriminals at UAB

What do fake NBA jerseys, black-market pills, and other people’s bank data have in common? They’re all available through cybercrime, and they’ve all been tracked by high school students learning to help catch the criminals at a weeklong camp at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Experts say there are about 350,000 cybersecurity job openings in the U.S., and that there aren’t nearly enough skilled workers to fight a rising tide of internet crime. But “Cyberdetectives Camp” is trying to prime that pipeline, not through simulated scenarios contrived for kids in a classroom, but through open-source investigations of real criminals.

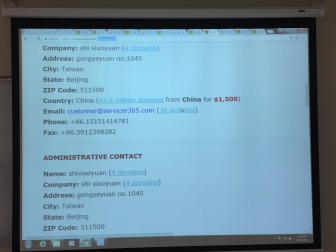

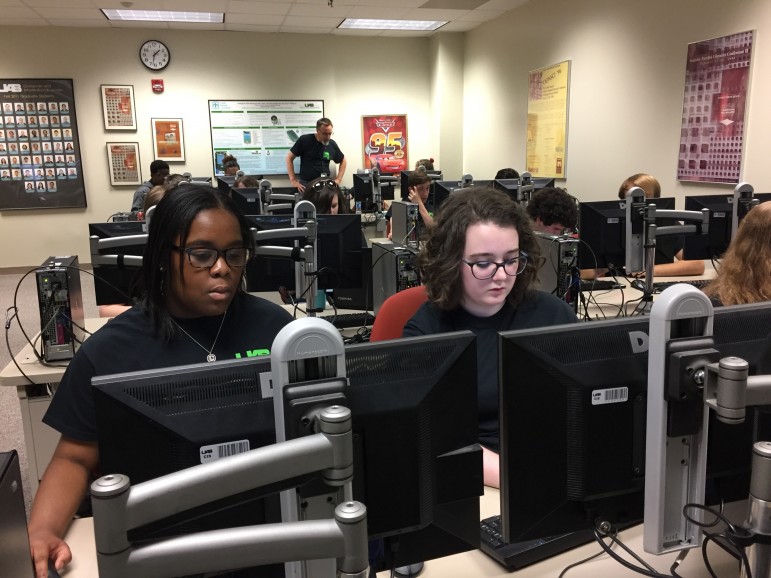

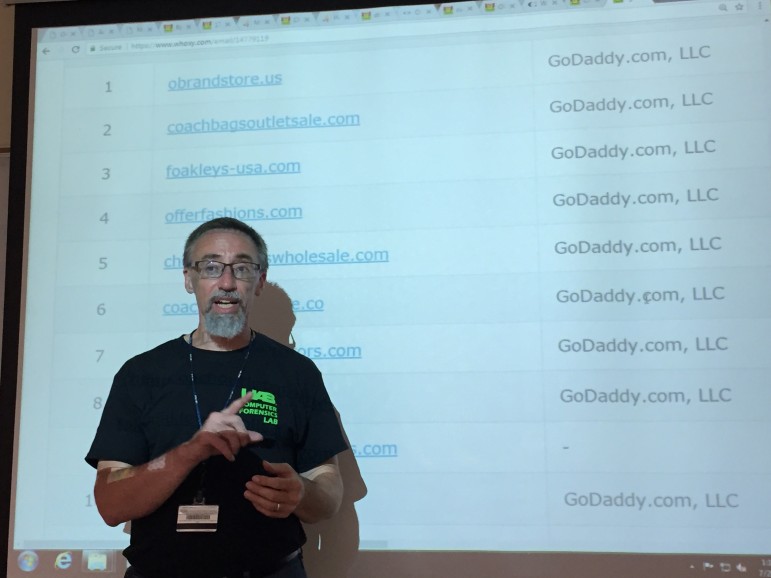

Each day of the camp was different, but the day I visited, the targets were people selling counterfeit NBA and soccer jerseys online around the world. Some of the 22 students had already discovered common IP and email addresses connecting a nation-straddling group of these fraudulent websites.

Gary Warner, UAB’s director of computer forensics research, reminded the students, “it’s in the Netherlands and it’s in China, but just because the company is headquartered in China doesn’t mean that they don’t have part of their network operating in the United States.”

Which means U.S. law enforcement could get involved in taking down the criminals, or at least their websites. It’s all about prioritizing through a series of steps, Warner says.

“Trying to find proofs of identity, then proofs of crime, and then prioritization – why is this criminal worth investigating?”

For example, if hundreds or even thousands of counterfeit websites are traced to one person, one computer, or one email, that’s more likely to be a high-priority target and more efficient to prosecute. And Warner’s cyber-campers have found those types of targets.

“The students were able to identify a lot of the email accounts, and those have already been referred over for the FBI to investigate,” he says.

Phishing scams, forensic hard-drive analysis, ransomware – they’re tackling all of it. But there’s a troubling backdrop here: Analysts predict that within five years there’ll be a shortage of about two million cybersecurity workers worldwide.

High school senior Sarah Newton of Douglasville, Georgia might soon help fill that gap. She’s checking out a sketchy-looking website called International Drug Mart.

“We found 34 domains, which are other websites, that are registered to that same email address,” she says. Basically, she’s following a trail. I ask her if that’s one of the challenges she likes about this kind of work. “Absolutely,” she says.

Hoover High School graduate Will Thomason agrees. He’s “pinging” or probing computer networks around the world to try to reveal connections between sites that sell fake goods.

“And then we can put that into a report that gets turned in to the FBI. And then they can launch an investigation,” says Thomason. “This is definitely a great way to spend a week.”

Warner and other educators hope that the interest lasts more than a week. They’re looking for career cybercrime fighters.

“We’re trying to show people who may not have a typical computer-science, geek-from-age-three background that there are lots of exciting careers in computer science and in criminal justice,” says Warner, who plans to hold the camp again next summer. He says businesses, governments, the military, hospitals – basically any legal enterprises – are going to need a lot more people who can tangle with cybercriminals.

Rodney Petersen, director of the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education, backs that up. He says projections are “by the year 2022, there will be a shortage of 1.8 million cybersecurity workers worldwide.”

And in Alabama, he says, “the data shows that there were over 3,000 open positions in cybersecurity last year, and even more specifically, there were 193 open jobs in the area of investigations … So that’s why summer camps like this are critically important, not only for the state of Alabama, but for our national effort to reduce that workforce gap.”

But after watching Warner’s high-schoolers track crafty cybercriminals, a question nagged: what if these budding cyber-experts take their skills over to the dark side where there’s potentially money to be made? I ask Warner if there’s an ethical issue here.

“Yeah, absolutely. In fact, what I tell my students here is, if any of you decide to go that way, you know who I am, I know who you are, and I will be the one that comes after you myself.”

He’s chuckling, but from this well-known cybersleuth, that’s not a promise to be taken lightly.

Supreme Court appears split in tax foreclosure case

At issue is whether a county can seize homeowners' residence for unpaid property taxes and sell the house at auction for less than the homeowners would get if they put their home on the market themselves.

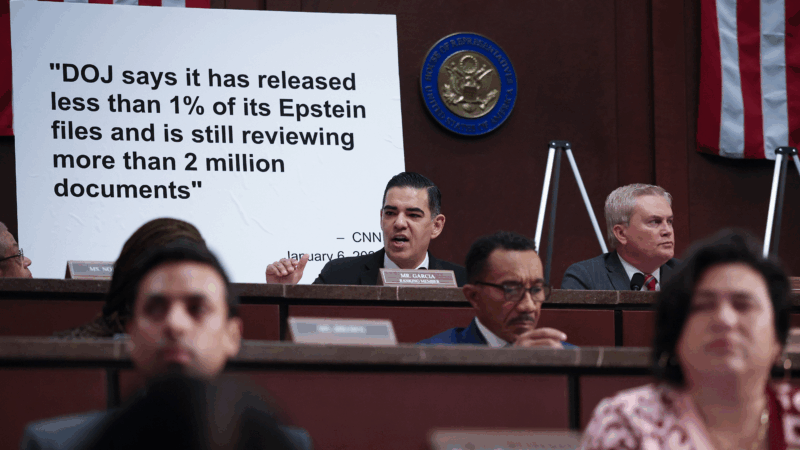

Top House Dem wants Justice Department to explain missing Trump-related Epstein files

After NPR reporting revealed dozens of pages of Epstein files related to President Trump appear to be missing from the public record, a top House Democrat wants to know why.

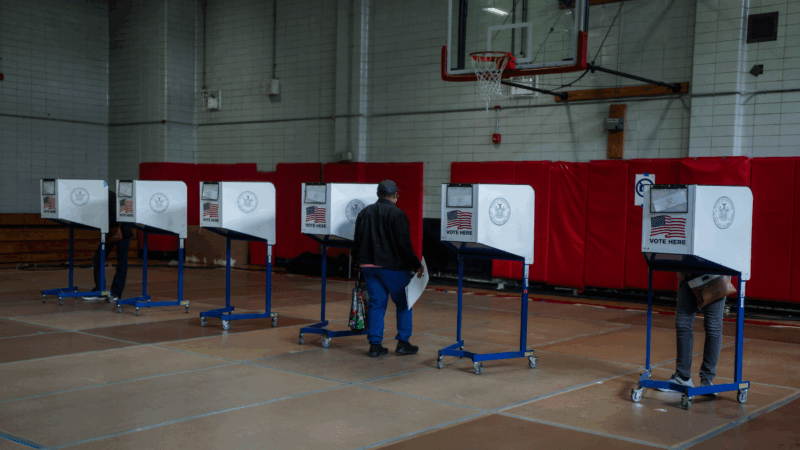

ICE won’t be at polling places this year, a Trump DHS official promises

In a call with top state voting officials, a Department of Homeland Security official stated unequivocally that immigration agents would not be patrolling polling places during this year's midterms.

Cubans from US killed after speedboat opens fire on island’s troops, Havana says

Cuba says the 10 passengers on a boat that opened fire on its soldiers were armed Cubans living in the U.S. who were trying to infiltrate the island and unleash terrorism. Secretary of State Marco Rubio says the U.S. is gathering its own information.

Surgeon general nominee Means questioned about vaccines, birth control and financial conflicts

During a confirmation hearing, senators asked Dr. Casey Means about her current positions and her past statements on a range of public health issues.

Rock & Roll Hall of Fame 2026 shortlist includes Lauryn Hill, Shakira and Wu-Tang Clan

The shortlist also includes a 1990s pop diva, heavy metal pioneers and a legendary R&B singer and producer.