History Professor’s Book Reconstructs One African-American’s Legal Saga

When Caliph Washington was stopped by a police officer in July 1957, he had no idea that moment would send him on a legal journey that would consume the next 13 years of his life.

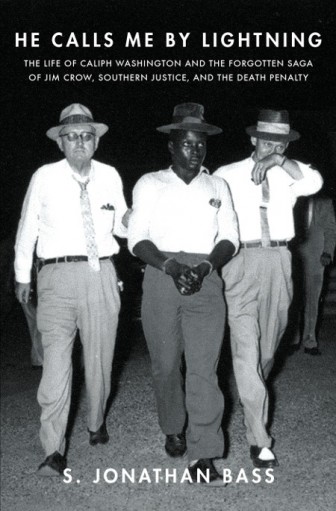

Washington was a 17-year-old African-American living in Bessemer. And he’s the subject of Samford University history Professor Jonathan Bass’ new book “He Calls Me By Lightning.” Bass says when he first heard of Washington’s case, he thought he might write an article about it.

“But then the more I talked to people, the more I realized that there was something much more significant about this story than met the eye,” says Bass.

On a hot July night in 1957, Lipscomb police officer James “Cowboy” Clark was following a tip of a bootlegger. Clark was untrained and had been on the job only about six months.

He spotted Caliph Washington as the teen drove home from a date. Clark began tailing Washington, initially without any lights or siren. Washington, fearful of an attack by Klansmen or others, which was common at the time, sped off. Clark shot at the car and chased Washington into Bessemer. Eventually, Clark turned on his lights and siren, at which point Washington pulled off the road and crashed the car into a tree.

“Clark got out of the patrol car, stomped up angrily, according to Caliph, and began asking him, demanding Caliph tell him where the whisky was,” says Bass.

Bass says Washington calmly responded that he didn’t know anything about whisky, which apparently made Clark angrier. He demanded Washington get out of the car and then led him to the patrol car.

Bass says what happens next isn’t entirely clear, but Washington said Clark pulled out his gun to pistol-whip Washington. The two began to scuffle over the gun and, with Clark’s finger likely on the trigger, the gun goes off. The bullet ricochets off the police car.

“[It] enters Clark’s body at a very odd angle and just slices his aorta,” says Bass. “He will be dead within 15 to 20 minutes.”

Enveloped by the Legal System

Caliph Washington fled and eventually got on a bus traveling to Memphis. Police conducted a manhunt, captured Washington in Mississippi and brought him back to Alabama for trial on a charge of premeditated murder.

But with Jim Crow in force, Bass says it is as if the system was stacked against Washington at every turn.

“Being poor and being African-American was a deadly combination in terms of your ability to get quality legal representation,” says Bass.

Bass says Washington’s court-appointed lawyer was only in place ten days before the trial and had a reputation as an ambulance chaser.

“The evidence is so clear,” says Bass when looking at trial transcripts. “The attorney is not connecting the dots …This is not first degree murder.”

Washington did receive council from two prominent black lawyers at the time, David Hood and Orzell Billingsley.

It was also illegal to exclude black men from the jury, but officials in Bessemer found other ways to keep them from the jury pool.

Washington was convicted and sentenced to death in 1957. That would be overturned on appeal. A second trial in 1959 resulted in the same verdict and sentence.

He waited on Alabama’s death row for years, and Bass says Gov. George Wallace could be credited with keeping Washington alive. That’s because Wallace stayed Washington’s execution 13 times.

“I looked at Wallace’s views on the death penalty and was very surprised about how opposed to the death penalty he seemed to be,” says Bass.

For unknown reasons, Wallace denied a 14th stay, and Washington was within hours of going to the electric chair before a federal judge blocked it.

Washington remained in Alabama’s hellish prison system until 1970 when he faced a third trial. An integrated jury convicted him again, but did not sentence him to death. An appellate court overturned the conviction and freed Washington. But it left the possibility of a fourth trial.

Life After

The prospect of a fourth trial hung over Caliph Washington the rest of his life, although it never happened. He married and worked to move on after 13 years behind bars.

Bass says Washington came from a religious family, but being in prison and facing death left him a changed man.

“He decided that God had set him aside for a bigger purpose,” says Bass.

He became a minister of a small church in Lipscomb. In the early 1970s he bought a large van and began driving through Bessemer neighborhoods. He would stop and talk with young black men, share his story, and work to keep them off the streets.

Washington’s name is part of a Supreme Court case, Washington v. Lee, which integrated prisons. But Bass says Washington’s experience does something more basic for historians. It reveals how discrimination in the legal system worked at an individual level.

“[His] story reveals so much about how Jim Crow operated from the local all the way up to the state supreme court,” says Bass.

Hear an extended interview with Bass:

Mass trial shines a light on rape culture in France

A harrowing and unprecedented trial in France is exposing how pornography, chatrooms and men’s disdain for or hazy understanding of consent is fueling rape culture.

What’s your favorite thing about fall?

With cooler mornings and shorter days, if feels like fall is finally here. So what’s your favorite thing about fall? We put that question to people at our recent News and Brews community pop-up in Cullman.

Teammates LeBron and Bronny James make history as the NBA’s first father-son duo

The Jameses, who both play for the L.A. Lakers, shared the court for several minutes on the NBA's opening night. They join a very small club of father-son teammates in American professional sports.

After John le Carré’s death, his son had the ‘daunting’ task to revive George Smiley

Nick Harkaway grew up hearing his dad read drafts of his George Smiley novels. He picks up le Carré's beloved spymaster character in the new novel, Karla's Choice.

When Steamboat goes WHOOSH, scientists look for answers

What triggers geysers to go off is still not well understood. A new paper shows that one small earthquake likely triggered an eruption of the world's tallest active geyser, Steamboat.

Trump’s ex-chief of staff warns his former boss would rule like a ‘fascist’

John Kelly is one of several Trump-era White House officials to publicly criticize their former boss, arguing that Trump is not fit to hold office again.