Self-taught Alabama Artist Thornton Dial has Died

Self-taught, African-American artist Thornton Dial has died at his home in McCalla. He was 87.

Dial was born to sharecroppers in Emelle in Sumter County in 1928. He moved to Birmingham at age 13 to live with a great aunt.

“I always had the idea to draw,” Dial told the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, a non-profit dedicated to the work of self-taught, African-American artists. “I put in more time with drawing than I did with my lessons.”

Dial later worked building rail cars for the Pullman Standard Company at the firm’s Bessemer plant. He recalled in the same interview the secondary status that came with being black in that era.

“They had this punching iron with a hydraulic cylinder. They didn’t have anything behind the cylinder to hold it in and keep it from blowing out. It was costing them money. They would lose cylinders and lose production. I had the idea how to correct that problem and save them a lot of money. I had Clara [Dial’s wife] write it out, and I drawed[sic] pictures to show how it worked and give all of it to the people down in the office. About two or three weeks after, all that stuff started to get did in the factory. A white man I worked with, he said to me, ‘There go your patent.’”

Dial’s art drew on politics and race. He was known for paintings and sculptures made of found objects such as plywood, rope, or steel from Birmingham’s iconic blast furnaces.

He also made yard art ranging from huge metal sculptures to fishing lures. Dial’s son, Richard Dial, said in 2011 despite health problems, his father continued to create into his 80s.

“If he breathed, he gonna try to create something,” said Richard Dial. “That’s been the way that he’s been all of my life.”

Thornton Dial was not well known within Alabama and his work might have gone unnoticed by the wider art world if not for Atlanta art collector Bill Arnett.

Arnett publicized Dial’s work in the late 1980s leading to shows at top museums around the country. Dial’s art is now in collections including those of the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington.

“I think this thing went way further than he had imagined in his mind,” said Richard Dial. “I would say the same thing about the family. I never thought that he would get this type of recognition from the art.”

But Thornton Dial’s recognition highlights tension between black artists and the white-dominated art community. Art critics sometimes referred to his work as “outsider,” “folk” or “primitive” – terms that can been seen as pejorative.

Filmmaker Celia Carey created the documentary “Mr. Dial has Something to Say” which aired on Alabama Public Television in 2007. She compared black visual artists’ relationship with the art world as that of black jazz, blues and gospel musicians who saw their style appropriated by famous white musicians.

“It’s not unprecedented in history,” Carey said. “Pablo Picasso, people now understand very well that cubism was born from his introduction, his awareness of African art that was pouring into Paris from the colonized African countries.”

Regardless, Dial won accolades from curators, critics and collectors. In that 2007 APT documentary Bill Arnett placed Dial’s art beside the greatest names of the field.

“You could go back 100 years and be living in Paris and you could kind of check in from time to time on Matisse and on Picasso,” said Arnett. “I feel the same way.”

Deadline looms as Anthropic rejects Pentagon demands it remove AI safeguards

The Defense Department has been feuding with Anthropic over military uses of its artificial intelligence tools. At stake are hundreds of millions of dollars in contracts and access to some of the most advanced AI on the planet.

Pakistan’s defense minister says that there is now ‘open war’ with Afghanistan after latest strikes

Pakistan's defense minister said that his country ran out of "patience" and considers that there is now an "open war" with Afghanistan, after both countries launched strikes following an Afghan cross-border attack.

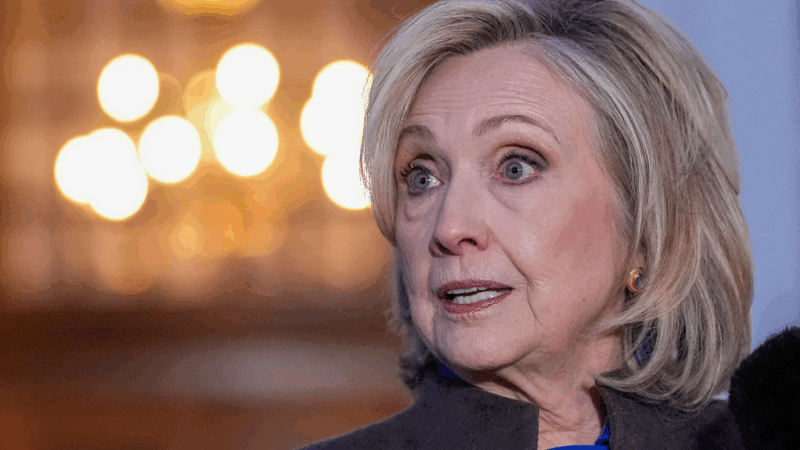

Hillary Clinton calls House Oversight questioning ‘repetitive’ in 6 hour deposition

In more than seven hours behind closed doors, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton answered questions from the House Oversight Committee as it investigates Jeffrey Epstein.

Chicagoans pay respects to Jesse Jackson as cross-country memorial services begin

Memorial services for the Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr. to honor his long civil rights legacy begin in Chicago. Events will also take place in Washington, D.C., and South Carolina, where he was born and began his activism.

In reversal, Warner Bros. jilts Netflix for Paramount

Warner Bros. says Paramount's sweetened bid to buy the whole company is "superior" to an $83 billion deal it struck with Netflix for just its streaming services, studios, and intellectual property.

Trump’s ballroom project can continue for now, court says

A US District Judge denied a preservation group's effort to put a pause on construction