Commentary: Not Easy to Find “Home” with Birmingham’s Redlining History

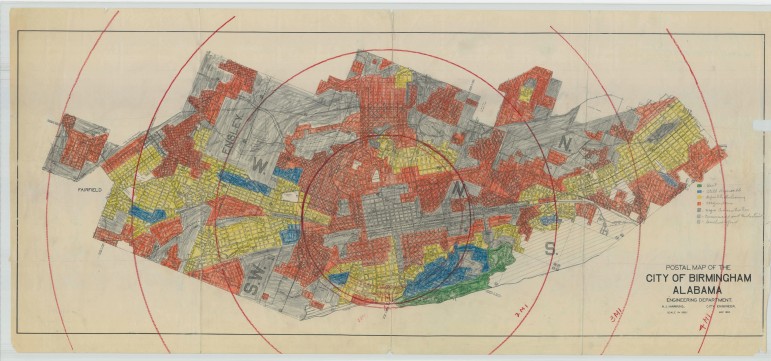

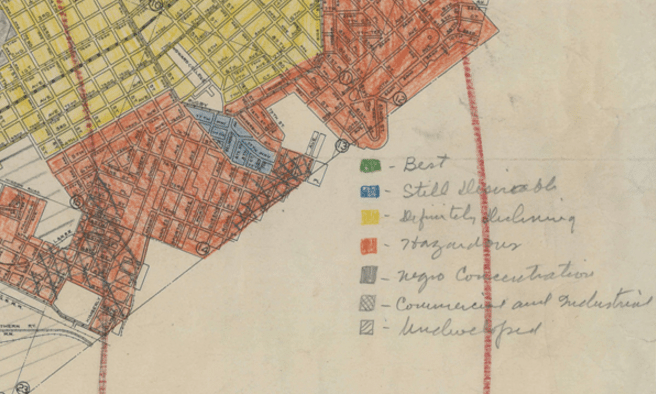

In the 1930’s, the Federal Housing Authority practiced “redlining,” denying services to people in certain areas based on racial or ethnic makeup. This mostly discriminated against black, inner city neighborhoods. In Alabama, Birmingham was no exception. The echoes of redlining can still be heard today, especially when young black families start house shopping. In this commentary, young adult author and WBHM staffer Randi Revill shares her thoughts on searching for home among Birmingham’s silent but ongoing racial division. Revill’s first novel, “Into White,” comes out this Fall.

As a child, I loved visiting my grandparents. Their tiny red and white house stood in the heart of Smithfield, near Elyton Meat Center just over the Center Street railroad tracks. I could get lost in my grandfather’s tales of W.C. Handy and other blues musicians while devouring my grandmother’s ambrosia, but even as a child, I wondered why they chose to live in racially segregated Smithfield. When I discovered redlining, I began to understand that they didn’t choose Smithfield. Smithfield was chosen for them.

In the 1930s, Birmingham’s officials sliced out neighborhoods for black families, funneling them into approved areas. In those redlined communities, the budget for community aesthetics was slashed, leaving roads unpaved and yards overgrown. Meanwhile, the Birmingham suburbs, affectionately referred to as Over the Mountain, raised in status and value.

For years, I toiled with the thought of my sweet grandparents being stripped of the freedom to choose where they could lay their heads, but it’s hard to know what to do with those feelings. Those officials are long dead, and I’m free to live wherever I want. So I filed redlining alongside other injustices my ancestors endured, and decided to move forward. That is, until my husband and I began searching for a neighborhood of our own.

In search of the perfect community, I went on GPS-free, self-guided, neighborhood-hops around Birmingham. I’d start near Eastlake Park, and ride 1st Avenue into the heart of the city. I’d hang a right at John’s City Diner straight into the hills of North Birmingham. Then I freestyle it. Looping and looping through the Northside, and riding out Center Street until it T-boned with Green Springs Highway. Then I’d take a left by the Heritage Shopping Center which leads to the “over the mountain” communities. First Homewood, then Vestavia, then I’d get completely lost in Mountain Brook, and somehow emerge into Forest Park. Lastly, I’d cut through Avondale to get back onto 1st Avenue, and stop by East 59 for a celebratory cup of coffee.

But after a few of these tours, I realized the red line still exists in our city. In 2016, Birmingham is still deeply segregated, and as a young family seeking diversity, community, and safety, which side of the red line do we choose?

I’m frequently told to move “over the mountain” where the tree-lined sidewalks are safe and clean. That’s the obvious choice for a sweet young married couple, but I hesitate since my grandparents wouldn’t have been allowed to live there when they were a sweet young married couple. Their only access points into those homes were as maids and janitors. Some say it’s my responsibility to move back to Smithfield and help cure the problem from the inside. To heal decades of damage designed by a system created before my mother was even born.

I want to ask my grandparents what they think. Would they be disappointed if we moved back to Smithfield? Would choosing an “over the mountain” neighborhood dishonor their sacrifices? But I can’t ask them. My grandfather’s wise council and grandmother’s ambrosia only live in my memories now, but the effects of redlining are still dividing our city.

Taking a red pen to the map in the 1930s and carving concentrated areas for black families has shaped the racial landscape of the city, and many diverse young families are leaving since they don’t fit on either side of the red line.

My husband and I are still figuring it out for ourselves, but Birmingham as a whole must make an effect to stop shutting our eyes to the division, or it won’t change. I encourage every resident to tour our city – GPS free.

This commentary is part of WBHM’s “Y’all Talk” series, and was produced by Amy Sedlis. Find out more about how YOU can submit a commentary here.

Supreme Court appears split in tax foreclosure case

At issue is whether a county can seize homeowners' residence for unpaid property taxes and sell the house at auction for less than the homeowners would get if they put their home on the market themselves.

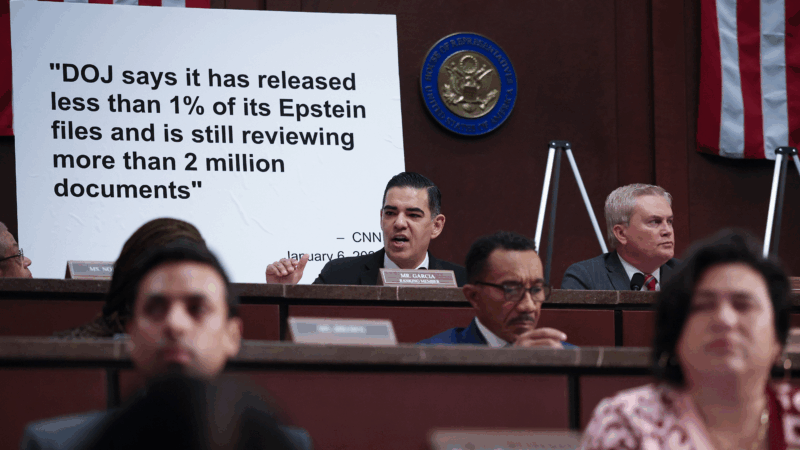

Top House Dem wants Justice Department to explain missing Trump-related Epstein files

After NPR reporting revealed dozens of pages of Epstein files related to President Trump appear to be missing from the public record, a top House Democrat wants to know why.

ICE won’t be at polling places this year, a Trump DHS official promises

In a call with top state voting officials, a Department of Homeland Security official stated unequivocally that immigration agents would not be patrolling polling places during this year's midterms.

Cubans from US killed after speedboat opens fire on island’s troops, Havana says

Cuba says the 10 passengers on a boat that opened fire on its soldiers were armed Cubans living in the U.S. who were trying to infiltrate the island and unleash terrorism. Secretary of State Marco Rubio says the U.S. is gathering its own information.

Surgeon general nominee Means questioned about vaccines, birth control and financial conflicts

During a confirmation hearing, senators asked Dr. Casey Means about her current positions and her past statements on a range of public health issues.

Rock & Roll Hall of Fame 2026 shortlist includes Lauryn Hill, Shakira and Wu-Tang Clan

The shortlist also includes a 1990s pop diva, heavy metal pioneers and a legendary R&B singer and producer.