Restoring the Lyric

As officials work to restore the Lyric Theatre in downtown Birmingham some obstacles could be expected: funding the project, removing lead paint and plumbing issues. But there are tougher, less obvious challenges too. When the Lyric opened in 1914, Birmingham was a city with lines of segregation and the theatre reflects that. So how do you faithfully restore a historic building still physically marked by the city’s racist past?

When the Lyric opened, it was one of the first theaters in the South where blacks and whites could see the same show at the same time for the same price. But it was still segregated.

Whites entered the theatre on 3rd Avenue North, which had an ornate marquee. Blacks entered through a separate door on 18th Street. Whites entered through the main lobby and sat close to the stage. Black patrons followed a hallway that led to the colored balcony.

Glenny Brock is the Volunteer Coordinator for Birmingham Landmarks, the nonprofit responsible for the restoration of the Lyric Theatre and Alabama State Theatre. To call Brock a mere cheerleader for the Lyric is an understatement. She’s especially passionate when it comes the fate of the colored balcony and colored entrance.

“I have never wanted anyone to have the sense that we are preserving the colored entrance and colored balcony because we’re like, whistling Dixie. I have never wanted it to come off as anything other than a recognition of ‘this is who we were,'”says Brock.

Birmingham Landmarks has already diverged from history with the entrances. Both now have identical marquees which lead to the main lobby, eliminating any separation. But they are still wrestling with what to do with the colored balcony and they have a lot of options. The chairs that were installed in the 1940’s could be restored. Some of the chairs could be donated to the Civil Rights Institute. Bleachers, the original seating in the colored balcony, could be reinstalled.

“It’s something we have to be real sensitive to,” says Danny Evans chairman of the Birmingham Landmarks board. Evans, Brook, and Birmingham Landmarks Executive Director Brant Beene has been reviewing options for the future of the formerly segregated spaces. “We don’t want there to be any current separation or segregation or any indication like that. If it has significance it has a significance to remind us that those were wounds that we want to be healed but that we don’t want to forget.”

Brock echoes those sentiments. “I don’t think we’ll please everybody. But we just want to get it right.”

But when it comes to historic preservation, how do you define ‘getting it right?’ It’s a tough call, says former Auburn University history professor Wayne Flynt.

“If you don’t put the segregated stuff back in the Lyric, that’s basically saying ‘that was the way it was when it was a functioning piece of Birmingham history.’ If you do leave the segregated seating in there, it’s a constant reminder to people who go in there, but no one who goes in there is unaware of what happened anyway.”

Flynt says white staff members of Birmingham Landmarks are bound to experience unease when confronted by the Lyric’s past. Still, he says, it’s part of Birmingham’s history and can’t be ignored.

“As a historian I must confess that what I would tell white people in Birmingham is: get over it. You are what you are. Back there, there’s nothing you can do to make that story different than what it is. So what you do is incorporate it and you use it to point out how far Birmingham has moved.”

Retired historian, Dr. Horace Huntley, agrees the history of the Lyric should be incorporated in the restoration. As a black teenager in the 50’s and 60’s, Huntley experienced the segregation in the Lyric first hand.

Despite those memories, Huntley is looking forward to the reopening. He says the Lyric could have an important role in the revitalization of downtown, a role it can only play with its doors open. So it’s hard for him to understand the fear of not getting the restoration right.

“I don’t think there’s a need to be concerned about what it will be. We know what it will not be and that is important to me as a person who grew up in Birmingham. It will not be the same Lyric.”

Organizers plan to reopen the Lyric sometime in 2014, the same year as its 100th birthday. They hope the old vaudeville theatre can become a place for everyone to gather, without forgetting the separation of the past.

Iran’s Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is killed in Israeli strike, ending 36-year iron rule

Khamenei, the Islamic Republic's second supreme leader, has been killed. He had held power since 1989, guiding Iran through difficult times — and overseeing the violent suppression of dissent.

‘One year of failure.’ The Lancet slams RFK Jr.’s first year as health chief

In a scathing review, the top US medical journal's editorial board warned that the "destruction that Kennedy has wrought in 1 in office might take generations to repair."

Here’s how world leaders are reacting to the US-Israel strikes on Iran

Several leaders voiced support for the operation – but most, including those who stopped short of condemning it, called for restraint moving forward.

How could the U.S. strikes in Iran affect the world’s oil supply?

Despite sanctions, Iran is one of the world's major oil producers, with much of its crude exported to China.

Why is the U.S. attacking Iran? Six things to know

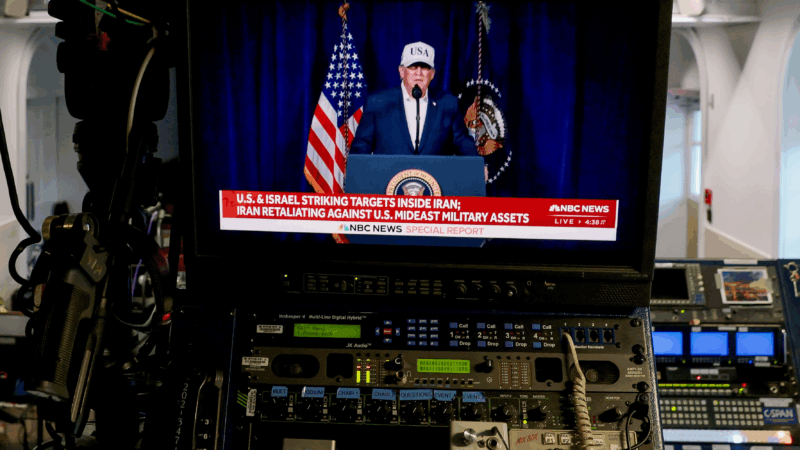

The U.S. and Israel launched military strikes in Iran, targeting Khamenei and the Iranian president. "Operation Epic Fury" will be "massive and ongoing," President Trump said Saturday morning.

Iran strikes were launched without approval from Congress, deeply dividing lawmakers

Top lawmakers were notified about the operation shortly before it was launched, but the White House did not seek authorization from Congress to carry out the strikes.