Tranquil Resource, Contentious Beginnings

About seven miles from Fort Payne is the northern gateway to a vision, a vision of a nearly hundred-mile “central park” between Birmingham, Atlanta and Chattanooga. Decades in the making, the conservation, tourism, and education opportunities are gelling in this huge green corridor. In Part Two of his series, WBHM’s Southern Education Desk reporter Dan Carsen has the intriguing story behind this growing resource:

A lot of people from Alabama, or fans of the group Alabama, know that country superstar Randy Owen once sang an anthem to his beloved Little River Canyon, which was a big part of his upbringing. A short walk away from the canyon is the Little River Canyon Center, a gleaming high-tech “green building” that’s becoming a campus, museum, community center, and tourist attraction. But a long walk, or a scenic drive, is what’ll begin to show you the scale of what’s happened here in the last few decades. If you’re in the Little River Canyon National Preserve anywhere near the “big falls” of the sometimes inaptly named Little River, you’ll hear them. It’s easy to tell why only the most daring kayakers even think about descending them, and why the Alabama Power Company considered trying to harness the energy in all that moving water. From 1912 to the early 90s, the company owned most of the land around the river. But generating power here was problematic.

As longtime resident and community leader Ricky Harcrow remembers, “It was a nightmare to dam it up the way that thing is, because of the gorge.”

In 1992, Congressman Tom Bevill called power company president and CEO Elmer Harris and asked the company to donate land for a national preserve. Harris Balked at a straight donation but agreed to give away some of the land and sell the rest for tax breaks and almost eight million earmarked federal dollars, which went into the company’s charity foundation.

Sound like a 14,000-acre win-win for all? Not so fast:

Says Harcrow, “There was a lot of opposition because of old landowners here. And a lot of ’em didn’t live here. It was kind of a retreat for ’em. [And people were concerned with] intervention by the government, taking over this that and the other.”

Even though the power company owned the land, people were fiercely attached to it, partly because the company allowed them to hunt on it. Pete Conroy, one of the Preserve plan’s main movers, says landowners and property rights groups from Washington got involved, too:

“The opposition really came from local folks who had been coerced by outsiders to distrust the process. I met really terrific people who had actually been told, ‘Yup, they’re gonna shoot your dog and burn your barn.'”

Lucky for the project, a “dream team” of Alabama Power, state government, allies in Congress, and local-boy-superstar Randy Owen saw the opportunity of what could be done and very publicly got behind it.

Conroy calls it a “partnership project,” adding, “A lot of us just spent a lot of time drinking coffee with folks, and gaining trust, and slowly but surely telling the story of what we thought would happen, and I think we really hit the right balance. There was not an inch of property taken by the government — no eminent domain, no condemnation. And I think that the National Park Service has really turned out to be a pretty good friend of the region.”

In October 1992, the Little River Canyon National Preserve became latest addition to the National Park System. People in the community — not to mention tourists I met from New York and Michigan — say the preserve and the Canyon Center are educational and economic boons to the area that enhance quality of life.

As people learn about the Preserve and the Center, all different kinds are taking advantage of the education and recreation programs, from class trips to Hindu weddings to rock-climbing to holiday programs held in Spanish.

“Next thing you know,” says Conroy, “there’s a nice family from Fort Payne that have always been here, hanging out with a nice family from Mexico City. Next thing you know, they’re having dinner together, and the next thing you know, their kids — ‘Oh, yeah, they go to the same school’ — and, it’s this community of people coming together to learn and be educated together.”

The larger plan for a green corridor from Little River Canyon in the North, down through protected areas to the Cheaha Wilderness in the south, is coming together. But thanks to decades of tenacity and good-old-fashioned people skills, there’s plenty for students, teachers, outdoors-people, and just regular folks to experience right now.

Oil prices rise sharply in market trading after attacks in Middle East disrupt supply

The high prices came as U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iran and retaliatory strikes against Israel and U.S. military installations around the Gulf sent disruptions through the global energy supply chain.

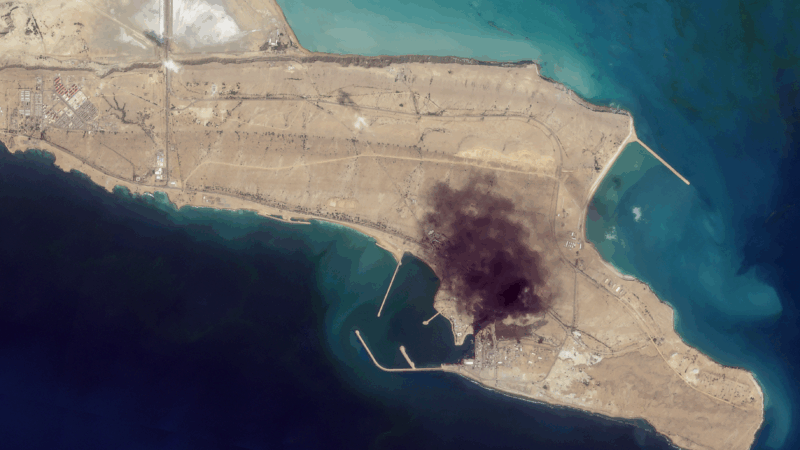

Satellite images provide view inside Iran at war

Satellite images from commercial companies show the extent of U.S. and Israeli strikes, and how Iran is responding.

Mideast clashes breach Olympic truce as athletes gather for Winter Paralympic Games

Fighting intensified in the Middle East during the Olympic truce, in effect through March 15. Flights are being disrupted as athletes and families converge on Italy for the Winter Paralympics.

A U.S. scholarship thrills a teacher in India. Then came the soul-crushing questions

She was thrilled to become the first teacher from a government-sponsored school in India to get a Fulbright exchange award to learn from U.S. schools. People asked two questions that clouded her joy.

U.S.-Israeli strikes in Iran continue into 2nd day, as the region faces turmoil

Israel said on Sunday it had launched more attacks on Iran, while the Iranian government continued strikes on Israel and on U.S. targets in Gulf states, Iraq and Jordan.

Trump warns Iran not to retaliate after Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is killed

The Iranian government has announced 40 days of mourning. The country's supreme leader was killed following an attack launched by the U.S. and Israel on Saturday against Iran.