Reverse Integration In A Birmingham School

Birmingham — Birmingham was at the heart of the Civil Rights Movement, a major front in the battles that ended legal

Birmingham — Birmingham was at the heart of the Civil Rights Movement, a major front in the battles that ended legal

segregation. When the schools were integrated, white people fled the city, taking resources and other

advantages with them. That continues today, but about two dozen families are bucking the trend and trying to reverse the

process. WBHM’s Southern Education Desk reporter Dan Carsen has the story:

Birmingham’s public schools are 95 percent black and 90 percent on free or reduced lunch. The system has been under state control since June and has been hemorrhaging students for decades. And at this point, it’s certainly not just white flight: many poor black families do

what they can to enroll their kids elsewhere. To put it mildly, Birmingham schools have a stigma.

So it was unusual when Laura Kate Whitney enrolled her four-year-old, Grey, in pre-K at Birmingham’s

Avondale Elementary.

“Our neighborhood school hosted an open house, and we were completely shocked,

in a good way, as to what we saw,” says Whitney.

She and her husband are white middle-class professionals and part of a group of two dozen similar

families who are not buying the conventional tradeoff — that if you live within city limits and have

means, you send your kids to private school, period.

Whitney’s friend Elizabeth Brantley also enrolled her four-year-old at Avondale, which last year was four

percent white. But Brantley grew up in nearby Mountain Brook, one of the whitest and wealthiest communities in

America. Her impressions of Avondale might come as a surprise:

“The minute we walked in, we were like, ‘this is just a normal school. This feels like

the kind of school that I went to when I was little.'”

These parents want convenience and higher property values, but they also really believe in diversity.

Whitney says she’s not concerned with her child being in a place where he looks different from the

other kids.

“I feel like at this age, they don’t really see color,” she says. “They go straight to playing

together, and learning about each other and talking and sharing snacks. I want him to have

those types of experiences. I mean, we live in a city that is extremely diverse.”

Researchers say in most cases of school gentrification, which is relatively rare, wealthier people move

into a newly desirable neighborhood, and the school’s demographics follow suit. But the area around

Avondale is already white and middle class. Unrelated to that, it’s actually one of the better schools in

the system. Even so, Avondale parent Katrisa Larry welcomes the new families.

“I love it,” she says emphatically. “We need them, most definitely.”

White students bring more fiscal resources, parental involvement, and subconsciously, higher

expectations, say researchers. And according to Tondra Loder-Jackson, Associate Director of the Center for Urban

Education at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, integrated schools confer many other benefits.

Summarizing a body of research, she says, “White graduates from those schools believe that they’re more open-minded

about race and less likely to stereotype. The black graduates, they’re more confident about

competing with whites, and they’re also not as likely to see whites as being categorically racist.”

But the white parents coming to Avondale aren’t counting on a love-fest. One possible stumbling block is that inner-city schools tend to be

more authoritarian, more “old-school,” relying on teacher-centered models of instruction as opposed to more progressive

methods favored by many middle-class parents, methods that involve kids initiating more of their learning.

Jennifer Stillman, a research analyst for the New York City Department of Education, just published a

book on school gentrification. She offers a warning:

“In America, we often try to sort of talk about how much we value diversity. But

when we talk about it, we sort of speak of it as in, ‘We’re all the same, and we just have to get

over our superficial differences.’ But people actually can be very different. And it can be

very uncomfortable to have this clash of parenting values.”

She and Loder-Jackson point out that it’s the middle-class “integrators” who have a choice — the families

who’ve already been in the community for a while usually don’t have the means to leave. If the new parents are

unhappy, Stillman says, the gentrifying group almost always falls apart and the kids go elsewhere.

But Stillman, who lives New York’s Harlem, respects the parents who do stick it out.

“Being an urban educator, I was extremely conflicted, and yet I couldn’t bring myself

to do it,” she admits. “I definitely have admiration for people who are out there trying to make

integration a reality.”

But parent Laura Kate Whitney is optimistic:

“It’s so funny that our kids can be the bridges that bring us together, and maybe

spread this throughout the city.”

Despite her good intentions, she acknowledges the next few months will be critical in shaping the future

at Avondale, and possibly at other even-more-challenging schools in this civil-rights crucible.

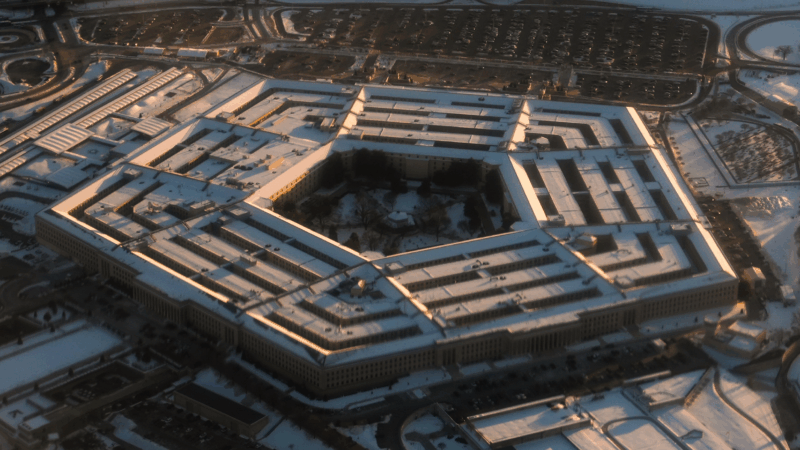

Pentagon puts Scouts ‘on notice’ over DEI and girl-centered policies

After threatening to sever ties with the organization formerly known as the Boy Scouts, Defense Secretary Hegseth announced a 6-month reprieve

President Trump bans Anthropic from use in government systems

Trump called the AI lab a "RADICAL LEFT, WOKE COMPANY" in a social media post. The Pentagon also ordered all military contractors to stop doing business with Anthropic.

HUD proposes time limits and work requirements for rental aid

The rule would allow housing agencies and landlords to impose such requirements "to encourage self-sufficiency." Critics say most who can work already do, but their wages are low.

Paramount and Warner Bros’ deal is about merging studios, and a whole lot more

The nearly $111 billion marriage would unite Paramount and Warner film studios, streamers and television properties — including CNN — under the control of the wealthy Ellison family.

Bill making the Public Service Commission an appointed board is dead for the session

Usually when discussing legislative action, the focus is on what's moving forward. But plenty of bills in a legislature stall or even die. Leaders in the Alabama legislature say a bill involving the Public Service Commission is dead for the session. We get details on that from Todd Stacy, host of Capitol Journal on Alabama Public Television.

My doctor keeps focusing on my weight. What other health metrics matter more?

Our Real Talk with a Doc columnist explains how to push back if your doctor's obsessed with weight loss. And what other health metrics matter more instead.