Price of Poverty: Food Deserts

What are the essentials of life? Food, water, and shelter. And to get those you have to have some kind of paying work or be enrolled in a government assistance program. But for the working poor (many of whom don’t qualify for government assistance) even the basics can be too expensive. They often cost more for working poor than for middle class people, as we’ll explore this week in our series “The Price of Poverty”. We start today with a report on food, from WBHM’s Tanya Ott.

In the City of Birmingham, there are 23 communities and within those communities 99 distinct neighborhoods. And where someone lives can play a big park in what he eats.

“When you leave here you’re going to get in your vehicles and stop by either Publix or Western or Winn Dixie or Piggly Wiggly to pick up a few things for dinner tonight,” said Birmingham Mayor William Bell in an address at the Health Action Summit in Hoover earlier this month. “But the people who live in La Quemada and neighborhoods like La Quemada – they don’t have those options.”

Never heard of La Quemada? It’s not easy to find on a map (hint: it’s behind the Birmingham International Airport). But Birmingham mayor William Bell says it’s a small part of town that points to a much bigger problem: Food Deserts.

Now food deserts have nothing to do with cactuses or rolling tumbleweed. Instead, they’re large areas with poor access to mainstream grocers offering an array of fresh fruits and vegetables. There may be plenty of food in a food desert, but it’s soda, chips, fried food, high-fat, salt-added — all the stuff we’re supposed to avoid.

“If you’re getting most of your food at the Dollar Store and the gas station, chances are your diet is not very good and over time, if that’s what you’re relying on, your health is not going to be as good as it would be if you were eating healthier foods that would support a healthier life.”

That’s Mari Gallagher. She’s a researcher who specializes in food deserts. The group Mainstreet Birmingham hired her to study the city, block-by-block. And what she found was that 88,000 Birmingham residents live on blocks that are food deserts. That’s 43 square miles of no easy access to fresh fruits and vegetables.

But Dr. Jamy Ard isn’t so sure the idea of food deserts holds up in Birmingham.

“We like stories that are simple. So we like headlines that say it’s a food desert and that’s why people are overweight. Those types of things make it easy for us to digest.”

Ard (a physician and nutrition sciences professor at UAB) says unlike New York City or Chicago, where food desert research was pioneered, 93% of Birmingham residents have a car and can drive several miles to a grocery store.

“The number of people who might be significantly impacted at the individual level I think could be limited.”

“Just because you have a car doesn’t mean you have the time or the gas money to go two or three times out of your neighborhood, around the mountain ridge to find the healthier store to get the food to bring it back home.”

Mari Gallagher says convenience is a huge factor. If a Dollar Store or convenience mart is much closer to a person’s home, he’s more likely to shop there than travel several miles to a traditional grocery store.

Access is One Issue. Price is Another.

Jamy Ard’s research suggests there’s not much price difference for fruits and vegetables bought in Birmingham’s lower income neighborhoods versus more affluent neighborhoods. But Ard’s study didn’t look at the quality of fresh produce in those communities and Mari Gallagher says often, in food deserts, it’s not as good.

“I was traveling on a project, and I played a little game with myself. I said, let’s see if somewhere along my route I can find a banana to have with my lunch. And wow – it was one of the hardest things to find a banana. And when I finally found one it looked like it had been kicked around a little bit. It was kinda half brown already, a little mushy.”

People on tight food budgets often complain that fresh fruit and vegetables aren’t the best deal because they spoil faster than packaged foods. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, Alabama has some of the higher fruit and vegetable prices in the country. It’s also one of only 13 states to tax food. This means Alabama’s working poor often pay a greater percentage of their income for food than other more wealthy Alabamians.

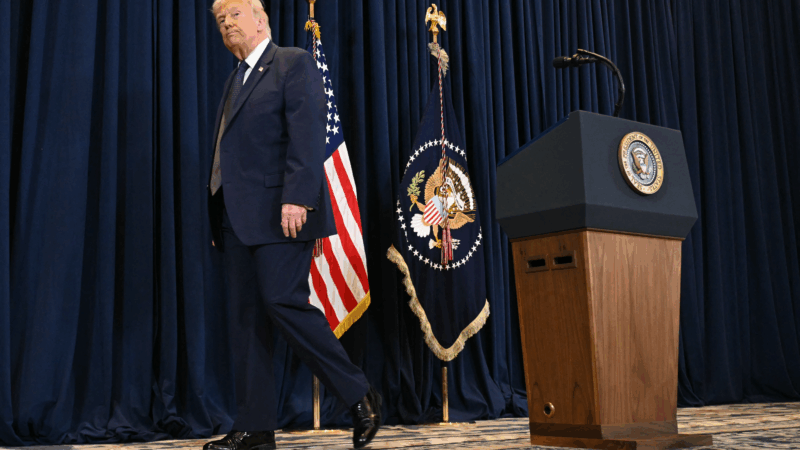

Trump’s war with Iran is angering some swing voters who want money spent at home

Swing voters who helped reelect President Trump in 2024 don't support his decision to go to war in Iran and instead want to see U.S. tax dollars spent tackling economic pressures facing Americans.

5 ways to resist the urge to keep looking at your phone

So you want to spend less time on your phone. How do you do that when it's designed to suck you in? Life Kit spoke to experts in behavioral science, psychology and technology for real-world advice.

The Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrant truckers shifts into higher gear

The White House wants tougher rules for commercial licenses after several high-profile crashes involving foreign-born drivers. But critics say that would do little to make the nation's roads safer.

Bam Adebayo’s 83-point night was one to remember. But not everyone was pleased

Detractors point to Adebayo's one-of-a-kind stat line — 43 field goal attempts, 22 3-point attempts and, most of all, NBA records of 36 free throws and 43 attempts — as proof of stat-padding.

Trump says Democrats must cheat to win. What do his supporters think?

NPR spent several days traveling across a pair of swing districts in Pennsylvania to find out. The answers show how much has changed since the 2020 election.

The government is investigating new claims that DOGE misused Social Security data

The fallout from DOGE staffers' efforts to access sensitive Social Security data continues as an agency watchdog disclosed a new investigation into "potential misuse" reported by a whistleblower.