Midwives in Alabama

Most babies in the U.S. are born in a hospital. But increasingly, moms who want more control over the process are choosing to give birth at home. Many of them get help from a midwife. But in Alabama that’s not an option because, as WBHM’s Tanya Ott reports, it’s illegal for midwives to assist in home births.

Shani Daly sits on the floor of her Mountain Brook office playing with her 9 month old daughter Zoe. Four years ago, when Daly was a grad student at MIT, she became pregnant with her first child. The pregnancy was low-risk, so her health plan assigned a certified nurse-midwife instead of an OB-GYN. Daly gave birth, in a hospital, and things went mostly according to plan.

“I think I had 21 hours of labor,” says Daly, “And then I actually just broke down and I said ‘epidural now! I don’t care what I said before. This is what you’re going to do for me!'”

Later, when Daly moved to Alabama and found out she was pregnant with Zoe, she decided she didn’t want to be tempted by the drugs in the hospital. So she started looking for a midwife to help with a home birth.

“And I couldn’t find any and I was like, what’s going on? I don’t understand why it’s so hard to find a midwife in Birmingham.”

It’s hard, because Alabama has some of the nation’s most restrictive laws on midwifery. There are many kinds of midwives ranging from lay midwives who are self-taught to certified nurse-midwives who are trained and licensed to provide gynecological care. In Alabama, only nurse-midwives are legal. And they can only deliver babies in a hospital under doctor supervision.

So, women who want to give birth outside a hospital setting have a couple of choices: give birth at home unassisted, try to find a midwife willing to risk prosecution for attending a home birth, or, once they’re in labor, drive to Florida or Tennessee to give birth. Jennifer Crook Moore has made that trip many times.

“It’s not easy.”

Moore is a certified professional midwife. She’s not a nurse, but she does have a master’s degree in public health. She also completed 3 years of midwifery coursework, including 1,300 clinical hours. She passed skills assessments and written exams and is accredited through a national organization.

Nine states and the District of Columbia expressly forbid certified professional midwives from practicing. There used to be more, but intensive lobbying by midwifery advocates has prompted some states to loosen the regulations. Moore is working with the Alabama Birth Coalition to change this state’s law. But she says it’s hard labor changing outdated perceptions.

“I remember the first day that I went to Montgomery,” says Moore. “And was walking the halls and the friendly legislators would be like, word is there’s a midwife here today and she’s well-educated and well-spoken and dressed nicely. You know, the implication being that holy cow! This midwife’s not a hippie and from the middle of nowhere. And she’s educated and has letters after her name.”

Moore says lobbyists from powerful medical organizations like to paint all midwives as lay midwives, then play up concerns about safety.

“Even a normal risk pregnancy could have an emergency type situation arise that wouldn’t be managed well at home,” according to Ashley Tamucci, an OBGYN at Brookwood Medical Center in Birmingham.

She worries about things like shoulder dystocia, where the shoulder gets stuck during delivery. Or a dropping heart rate, which would necessitate an emergency c-section.

“The American College of OB-GYNs requires that we be able to perform a c-section within 30 minutes of the time that it was diagnosed necessary. So, you know, is it feasible to get her stabilized, in an ambulance, transported to the hospital where the cesarean section could be performed within that 30 minutes window? I think that would be difficult.”

Still, Brookwood’s Dr. Tamucci isn’t convinced. She’s reminded of the story of two women, best friends in Atlanta, who had home births.

“One of them did great. Talked her other best friend into doing it,” says Tamucci. “And that one had a still birth. A full-term baby. Normal pregnancy. Perfectly normal mother. And I think she’s really regretting her decision to do it.”

David Reynolds thinks it’s bad public policy to make law on what could happen in a small percentage of cases. Reynolds is a pediatrician in Alabaster. He used to be president of the state Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“You know, our motto here in Alabama is ‘We dare defend our rights.” Alabama’s a state that really believes in individual rights. And yet here we are, probably one of the most important rights anyone has, where to deliver a baby, and we’re not allowing it to occur in a circumstance where there is safety involved. It seems not right to me.”

The Alabama Birth Coalition tried, unsuccessfully, to change the law during this last legislative session. Jennifer Crook Moore says they’ll try again next session. In the meantime, women like Shani Daly will have to continue making the long road trip out of state to give birth at someone else’s home.

Statement on lay midwifery from the Alabama Chapter-American Academy of Pediatrics

On behalf of the 675 pediatricians whom I represent as current president of the Alabama Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics, this statement is an effort to “set the record straight” regarding our Chapter’s position on lay midwifery in response to your recent Midwives in Alabama story. As advocates for children, the Alabama Chapter opposes legislation to allow lay midwifery in Alabama. We hold this position because of the healthcare risks associated with placing pregnant women and their babies in the exclusive maternity care of lay midwives.

First of all, we must resist the temptation to lower the standard of care for childbirth services. Certainly, childbirth is natural. Unfortunately, so are the potential life-threatening complications that can occur if births are not handled correctly. Half of the complications that occur during pregnancy occur during labor. Many of them cannot be predicted and when they do arise only highly skilled medical judgment and modern equipment stand between life and death.

A couple of generations ago, all babies were born at home. In the 1930s, the death rate for newborns was almost one in ten. It’s less than one in 100 now. And in 1935, the death rate for delivering mothers was 582 out of every 100,000. That number has dropped to approximately four in 100,000 now. Do we really want to turn back the clock?

In Alabama, it is lawful for a nurse midwife certified by the Alabama Board of Nursing as an advanced practice nurse to deliver babies in collaboration with a licensed physician. This collaborative model between nurse midwives and physicians guarantees rigorous standards for training and education. We support preservation of this model, which is essential to protect and maintain the public health and safety of both mothers and newborns.

James C. Wiley, MD, FAAP

President, Alabama Chapter-American Academy of Pediatrics

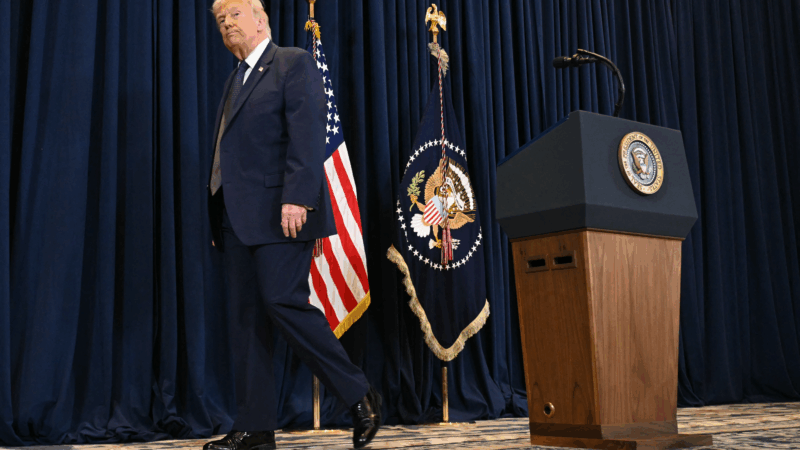

Trump’s war with Iran is angering some swing voters who want money spent at home

Swing voters who helped reelect President Trump in 2024 don't support his decision to go to war in Iran and instead want to see U.S. tax dollars spent tackling economic pressures facing Americans.

5 ways to resist the urge to keep looking at your phone

So you want to spend less time on your phone. How do you do that when it's designed to suck you in? Life Kit spoke to experts in behavioral science, psychology and technology for real-world advice.

The Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrant truckers shifts into higher gear

The White House wants tougher rules for commercial licenses after several high-profile crashes involving foreign-born drivers. But critics say that would do little to make the nation's roads safer.

Bam Adebayo’s 83-point night was one to remember. But not everyone was pleased

Detractors point to Adebayo's one-of-a-kind stat line — 43 field goal attempts, 22 3-point attempts and, most of all, NBA records of 36 free throws and 43 attempts — as proof of stat-padding.

Trump says Democrats must cheat to win. What do his supporters think?

NPR spent several days traveling across a pair of swing districts in Pennsylvania to find out. The answers show how much has changed since the 2020 election.

The government is investigating new claims that DOGE misused Social Security data

The fallout from DOGE staffers' efforts to access sensitive Social Security data continues as an agency watchdog disclosed a new investigation into "potential misuse" reported by a whistleblower.