Children’s Mental Health: Alabama’s Foster Care System

In the late 1980’s, a child who’s come to be known as R.C. was removed from his home because of allegations of abuse and neglect. R.C. was sent to a series of psychiatric institutions, even though he was not diagnosed with any serious emotional problems. Lawyers sued the Alabama Department of Human Resources on behalf of R.C. And in 1991, a federal court issued the R.C. Consent Decree. It required a massive overhaul in the way DHR provides mental health treatment to foster children in Alabama. The state is now lauded as a national model, but as Les Lovoy reports there are still big challenges.

Beverly Gardner’s home in Trussville, east of Birmingham, is a beehive of activity. She’s the mother of sixteen kids: four biological and 12 adopted. Gardner and her husband were foster parents for more than a decade, and now she’s an advocate for children in DHR’s foster care program. Despite the advances made since R.C.’s legal battle, Gardner says the agency still has problems.

“A lot of times, DHR will pull kids out of home because it’s dirty. Sometimes it’s just as simple as having somebody come into the home and help out with the housework. And, that’s a simple thing to take care of.”

Shuffling children from one foster home to another is a major concern for other child advocates, as well.

“The more that child moves while in foster care, the worst for his or her mental health.”

That’s James Tucker. He’s with the Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program or ADAP. And back in 1991, he was the guy charged with making sure the R.C. Consent Decree was followed.

“In fact, there’s research that shows that for every move beyond a third move while in foster care, that child is increasingly at risk for not being able to be a law abiding, tax paying citizen, ultimately.”

There are no hard numbers for how many foster kids have a serious mental illness. But Carolyn Lapsley, deputy commissioner of DHR, says the R.C. Consent Decree forced her agency to take a serious look at how it treated foster children with mental illnesses. Before, they tended to have a one size fits all philosophy. If a child exhibited a certain set of behaviors, he was quickly diagnosed with an illness, and treated or, in some cases, not treated. Lapsey says the R.C. decree forced them to look at each case individually. It also made them look outside their own agency for help if necessary.

“Our process has really been strengthened by that, it also says you may need other disciplines to be part of that decision making process and different kinds of evaluations. So, it made a tremendous difference in the child welfare system for us to evaluate children’s mental health needs, and then to access local services in order to meet them.”

There’s now a multi-needs committee made up of representatives from five state agencies – Public Health, Mental Health, Youth Services, DHR and Education. Multi-needs teams are formed locally, so foster children who are referred to the committee are helped by agencies close to home. James Tucker, of the Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program, says on paper it’s a great idea. But…

“The multi-needs planning process remains purely a bureaucracy. It’s paper being shuffled by officials of various agencies without any meaningful participation of child and family.”

“As far as just an exercise in bureaucracy, and paper shuffling. I know the individuals involved in that.”

Steven Lafraneure is director of Children’s Services for the Alabama Department of Mental Health.

“I know they take their job very seriously when they staff the reams of paper that come in on children who need services that their local communities cannot provide at this time and I would say a significant number of those kids are receiving those service today as a result of that process.”

Despite the debate over whether DHR’s systems are helping or hurting foster children, most advocates agree things are measurably better in Alabama than before the R.C. Consent Decree. Richard Wexler is director of the a private advocacy group called National Coalition of Child Protection Reform. He says Alabama’s DHR is a national model. But, he says, the term “model” is relative.

“Paul Vincent, who led so much of the reform effect in Alabama likes to say fixing a child welfare system is like fixing a bicycle while riding it. I would add riding it uphill, up a mountain. Alabama, in effect, is half way up the mountain. It is a national leader because most of the places in the country are still at the very bottom of the mountain.”

In 2007, a federal judge lifted the R.C. Consent Degree, meaning Alabama is no longer under government oversight. Child advocates worry the Department of Human Resources might backslide. But DHR officials insist that isn’t going to happen. No doubt child advocates and attorneys will be watching closely.

Supreme Court appears split in tax foreclosure case

At issue is whether a county can seize homeowners' residence for unpaid property taxes and sell the house at auction for less than the homeowners would get if they put their home on the market themselves.

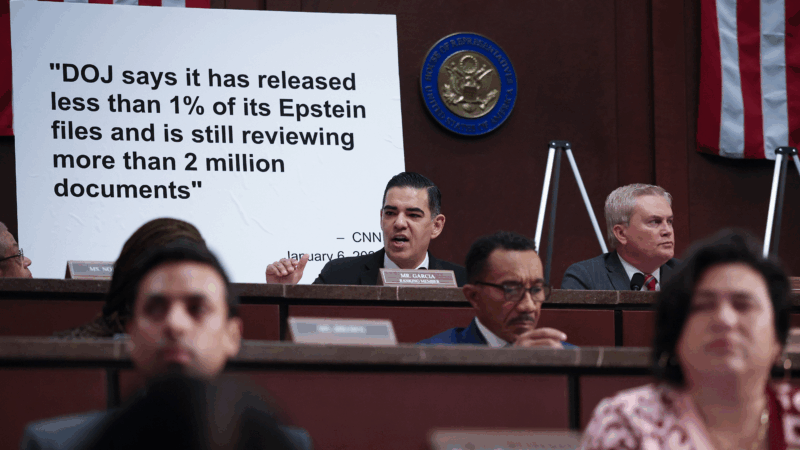

Top House Dem wants Justice Department to explain missing Trump-related Epstein files

After NPR reporting revealed dozens of pages of Epstein files related to President Trump appear to be missing from the public record, a top House Democrat wants to know why.

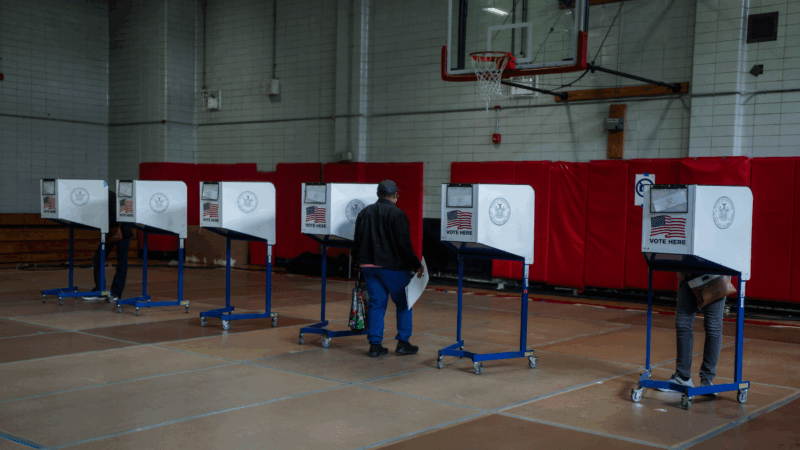

ICE won’t be at polling places this year, a Trump DHS official promises

In a call with top state voting officials, a Department of Homeland Security official stated unequivocally that immigration agents would not be patrolling polling places during this year's midterms.

Cubans from US killed after speedboat opens fire on island’s troops, Havana says

Cuba says the 10 passengers on a boat that opened fire on its soldiers were armed Cubans living in the U.S. who were trying to infiltrate the island and unleash terrorism. Secretary of State Marco Rubio says the U.S. is gathering its own information.

Surgeon general nominee Means questioned about vaccines, birth control and financial conflicts

During a confirmation hearing, senators asked Dr. Casey Means about her current positions and her past statements on a range of public health issues.

Kalshi reveals insider trading case against editor for MrBeast

With prediction markets booming, so have concerns about insider trading. Now, Kalshi has disclosed its first public actions against accounts suspected of trading on confidential information.