Alabama and the Oil Spill: Seafood Safety

The oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico is looming over the seafood industry. Early tests don’t show substantial chemical contamination of Gulf seafood. But officials have closed many fishing grounds. And that means we’re going to see more imported seafood in the coming months. But as WBHM’s Tanya Ott reports, some people question the safety of those imports.

Tom Robey runs around like a mad man. Or maybe a mad scientist. His laboratory is the kitchen.

“This is the beginning of New Orleans barbecue sauce for our shrimp dish,” he says, stirring a pot. “So it’s brown garlic and black pepper and rosemary and beer.”

Robey is executive chef at Veranda on Highland in Birmingham. But he learned his chops as a sous-chef at the famous Commanders Palace in New Orleans. Robey’s specialty is regional seafood: Louisiana crawfish, Florida crab, Alabama shrimp.

When the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded last month spewing oil into the Gulf, Robey shelled out nearly $3,000 to stockpile 600 pounds of shrimp. And it’s a good thing, because it’s not clear how extensive or long-term damage to Gulf seafood will be. Early tests don’t show substantial chemical contamination, but monitoring might have to continue for decades. Meanwhile, industry officials expect a shortage of domestic seafood. And other countries are ready to fill the gap.

We already import about 80% of our seafood. The oil spill is expected to drive that number higher. Tom Robey says he’ll take shrimp off the menu before he serves imported shrimp.

“I’m nervous about, like, how that seafood was handled, how it was fed, if it was farmed raised. I mean every day there’s some kind of recall on another product coming from China.”

He may have reason to be nervous.

“I think it’s really a buyer beware issue,” says Caroline Smith DeWaal. She’s director of the food safety for the Washington D.C.-based Center for Science in the Public Interest. She says when state regulators tested imported shrimp they found it was contaminated with antibiotics and other chemical residues that are illegal in the U.S.

“Some of these antibiotics are cancer causing agents. They also have been linked to anemia.”

Supporters of the industry say while some tests have caught problems that doesn’t mean all imported seafood is bad. Norbert Sporns runs a Seattle-based company called HQ Sustainable Maritime Industries. They farm tilapia, mostly in China. Sporns says the U.S. has a rigorous international certification process that will catch potential problems.

“Prior to export we are subject to a series of tests. Once a product lands in the United States there are other tests that can be administered by the FDA on a spot check basis, so there are multiple levels of security in place.”

But the FDA only inspects about 2% of imports. Right now, Congress is considering a bill that would give the FDA a lot more authority over imported seafood.

“I don’t see how they’re going to actually enforce any of that in the United States, let alone abroad.”

Ken Albala is a food historian at University of the Pacific in Stockton, California. He teaches and blogs about food policy and environmental issues. He says the FDA just doesn’t have the staff.

“Let me give you an example when they do inspections on beef. The USDA has a person in every slaughter house watching over everything that has to have their own separate office. And that’s just because historically beef is very controlled and regulated. Fishing hasn’t been, ever. And when you’re talking about a several thousand pound cow versus a bass, let alone a shrimp. I don’t see how they could ever begin to inspect consistently what’s coming in from abroad. Definitely not.”

So, at least for now, consumers who want to eat shrimp (and boy do we love our shrimp!) have two choices:

Trust that random spot checks find any problems with seafood imports or pay even more for domestic, wild harvested shrimp.

And that price could go even higher if the oil spill in the gulf contaminates a good part of the domestic supply.

‘Songs from the Hole’: The story behind JJ’88’s documentary and visual album

The visual album and documentary Songs from the Hole tells the story of James Jacobs, the hip-hop artist JJ'88, as he reflects on his coming-of-age within California's state prison system.

Oil price surges as Iran steps up attacks on ships in the Persian Gulf

Markets seesawed on Day 13 of the war in the Middle East, as two oil tankers were struck by projectiles near Iraq's southern ports and attacks between Israel and Hezbollah intensified.

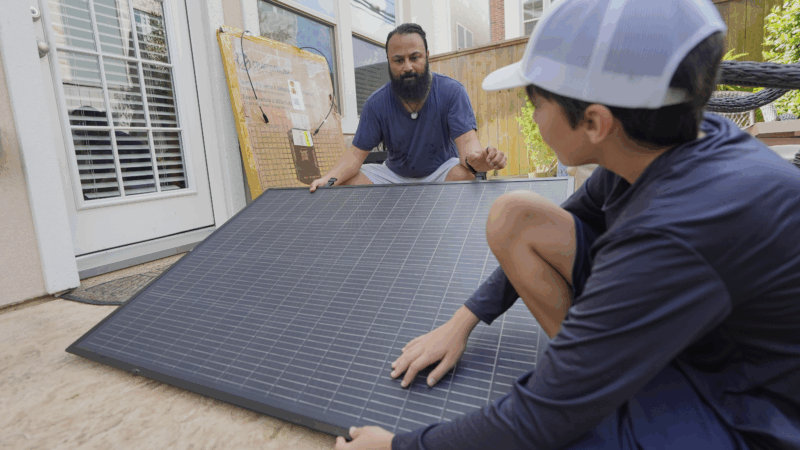

Easy-to-use solar panels are coming, but utilities are trying to delay them

Utilities are convincing lawmakers around the U.S. to delay bills that would allow people to buy solar panels, plug them into an outlet and begin generating electricity.

The Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrant truckers shifts into higher gear

The White House wants tougher rules for commercial licenses after several high-profile crashes involving foreign-born drivers. But critics say that would do little to make the nation's roads safer.

Trump’s war with Iran is angering some swing voters who want money spent at home

Swing voters who helped reelect President Trump in 2024 don't support his decision to go to war in Iran and instead want to see U.S. tax dollars spent tackling economic pressures facing Americans.

5 ways to resist the urge to keep looking at your phone

So you want to spend less time on your phone. How do you do that when it's designed to suck you in? Life Kit spoke to experts in behavioral science, psychology and technology for real-world advice.