Eating Alabama

Rising food and fuel costs, fears of bacteria and pesticide-tainted vegetables, and high rates of obesity are all turning more people to farmers markets, food coops and home gardens. But it’s not always an easy row to hoe, says Amy Vickers.

“I wanted a front yard where I didn’t have to have chemical fertilizers. I didn’t want to use a lawn mower. I wanted something that was organic, that was easy, that was more fun and more productive.”

Vickers lives in Homewood, where she owns the environmentally-friendly Red Rain General Store. She sits in her shady, front-yard garden surrounded by more than 100 varieties of locally-grown herbs, flowers, vegetables, shrubs and trees.

“I suppose that I’m one of the only people in this area that could grow 100 varieties of things to feed my family if I needed to or wanted to. I have the knowledge and its something that I’ve passed on to my daughter. Some of the plants that I grew were my great, great grandmothers and my great, great, great grandmothers and my great, great, great, great grandmother.”

Vickers loves that neighborhood kids hop off their bikes to grab handfuls of fruit. She also recalls an elderly man who walked up in her yard with a plastic bag, as she sat hidden by vines on the porch. But some of her neighbors view the garden as an eyesore. When the City of Homewood threatened her with fines, Vickers sued in federal court to keep her garden intact. In June, they reached a settlement, but Vickers still believes the process is subjective.

“If you have one person who has a complaint against you for really any reason, my understanding is that they can go after you for anything if someone doesn’t like it.”

Vickers doesn’t understand some of her neighbor’s impulse to edge their lawn two or three times a week… to think of a manicured lawn was a status symbol.

Plenty of people agree with Vickers. At the recent Birmingham Food Summit they listened to a slate of regional food speakers talk about developing a strategy to promote local foods. Rows of tables displayed literature from groups such as Heifer International, People-Helping-People-Farm, and Community Food Security Coalition. As participants mingled, nibbling on croissants and bagels, food systems expert Keecha Harris highlighted the issues.

“We really need to ask ourselves some hard questions about where our food comes from, what we consider to be food, what types of health outcomes we want, what types of farming we want to support and what does it mean now in the midst of the current gas crisis.”

She wants people to not only buy food grown locally but to grow their own food.

“There might be resistance. I know for African Americans, in particular, it’s a really big challenge thinking about food production because we have such a traumatic experience around land and farming. It’s not as intuitive as one might think.”

A new farmer’s market has taken root in Tuscaloosa, on the lawn of the Episcopal church, just off the University of Alabama campus. And on Thursday afternoons, you’ll find Joe Brown and his wife Sarah selling organic produce at the market. They grow a luscious array of basil, squash, zucchini and other veggies on their small farm, which they tend when he’s not working at the University and she’s not teaching school in Birmingham.

On this day, the Brown’s friends – Andy and Rashmi Grace – are also their customers. They’re shopping for the makings of a distinctly Alabama dinner. The Graces and Browns aren’t just casual consumers. Since April, the 20-somethings have been eating only food grown or raised in Alabama. Andy is a filmmaker, so he’s documenting their experiment. Gathered at the Grace’s home, a quaint cottage with gardens in the front and the back yard, they say it’s been a challenge. Joe and Rashmi says they regret not having canned or frozen veggies grown last spring, because Alabama produce doesn’t actually roll in until June or July.

“For the first month of the project the only fruit any of us had was strawberries because that was the only fruit in season.”

“And we haven’t had bread for 2 months. We started off with a can of 10-year old wheat and none of us could get it ground fine enough to make bread. We mainly used it for cream of wheat.”

The group scoured the state for wheat, but learned most of what’s grown is for animal, not human, consumption. Joe and Andy say their big wheat score came when a large-scale farmer allowed them to sneak a few pounds right off the combine.

(Joe) “To get grains, we’ve had to basically interrupt the agri-business supply chain! But not everybody could get that. That wheat is grown under contract to big mid-western firms who take it somewhere, mix it in with grains from other states and then a lot of it is actually trucked back here to Alabama.”

(Andy) “People just assume that if it’s ground here or distributed here, that it’s actually from here. But once you start asking questions you realize pretty quickly that our food ways are a lot more complicated than that. We’re asking harder questions about what we’re eating than I’ve ever asked about any substantial portion of my life, as rigorously as we’re eating now.”

(Joe) “I don’t even know as much about my own spiritual belief system than I know about where my breakfast came from.”

Alabama produces an incredible diversity of food: grains, dairy, potatoes, fruits and vegetables. Farmers can grow 10 or 11 months out of the year, almost year-round agriculture. Still, Andy Grace says with the way the current agri-business system works, it’s not viable for every Alabamian to eat the way he, his friends, and friends are. Sarah Brown agrees.

“One of the solutions would be — I don’t mean this in a ‘hippie concept’ of the word — but food co-ops. For the four of us, we try to help each other. I live closer to the dairy so I’ll go and I’ll buy a ton of it, and then supply it to them when they need it.”

They acknowledge not everyone can afford the freshly grown or certainly organic food. But in some instances the fresh stuff is cheaper because it’s traveled fewer miles. And, they argue, if you’re only buying nutritious fresh foods instead of expensive processed foods, you’re spending less money.

(Andy) “I just remember hearing all these stories about greens being such a staple of southern diets and they’re just not anymore. You can’t find collard greens in the store right now. They’re at the end of the season but they’re doing well right now. We’ve got a refrigerator full of them.”

(Joe) “I’ve often though that our diet was straight out of the Grapes of Wrath because we’ll be cooking a dinner and it will be like collards, bacon and corn bread. We’ve been eating what some people may call soul food but what is really is local, Alabama food.”

(Sarah) “You have to make a decision. You have to say, what is important to me? Do I have to have exactly what I want to eat? You can choose to eat goat cheese instead of having cow milk cheese. It’s what’s here and it’s what’s local.”

The Brown and Grace families spent countless hours researching, locating and traveling to purchase Alabama-grown food. They say it’s a radical and, right now, unsustainable lifestyle. But they hope it won’t always be.

‘Songs from the Hole’: The story behind JJ’88’s documentary and visual album

The visual album and documentary Songs from the Hole tells the story of James Jacobs, the hip-hop artist JJ'88, as he reflects on his coming-of-age within California's state prison system.

Oil price surges as Iran steps up attacks on ships in the Persian Gulf

Markets seesawed on Day 13 of the war in the Middle East, as two oil tankers were struck by projectiles near Iraq's southern ports and attacks between Israel and Hezbollah intensified.

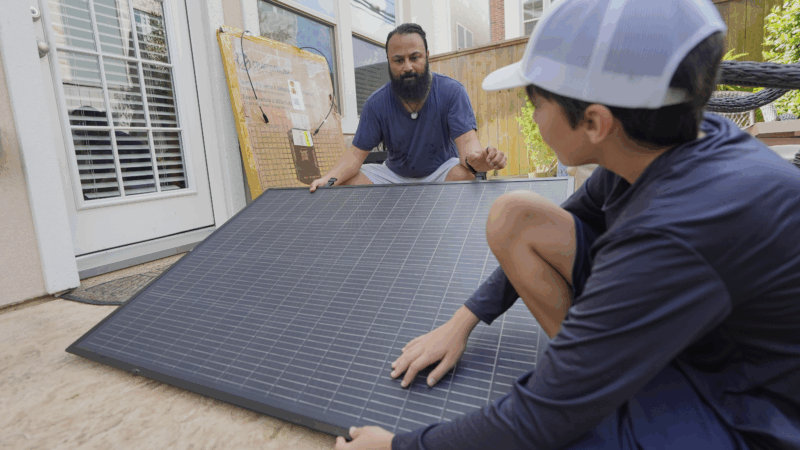

Easy-to-use solar panels are coming, but utilities are trying to delay them

Utilities are convincing lawmakers around the U.S. to delay bills that would allow people to buy solar panels, plug them into an outlet and begin generating electricity.

The Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrant truckers shifts into higher gear

The White House wants tougher rules for commercial licenses after several high-profile crashes involving foreign-born drivers. But critics say that would do little to make the nation's roads safer.

Trump’s war with Iran is angering some swing voters who want money spent at home

Swing voters who helped reelect President Trump in 2024 don't support his decision to go to war in Iran and instead want to see U.S. tax dollars spent tackling economic pressures facing Americans.

5 ways to resist the urge to keep looking at your phone

So you want to spend less time on your phone. How do you do that when it's designed to suck you in? Life Kit spoke to experts in behavioral science, psychology and technology for real-world advice.