Cave 9

It’s Thursday night, just after seven. As the sun sets on Birmingham’s Southside, three teenage boys hang out on a corner. Across the street there’s a tattoo shop and just down from that, a public housing project. 13 year old Taylor Prestage and 17 year old Houston Forman have come into town from Oak Grove and Pleasant Grove, respectively.

“This is the first time I’ve been and they dragged me out here,” Prestage says.

Forman adds, “I just like the scene and the type of music that comes along with it. And how I feel when I come here.”

“Here” is Cave9. It’s billed as an all-ages music club, but I am clearly the oldest person here. Most everyone else is in their teens and early 20s. The crowd starts to move inside as the musicians – a girls group called P.S. Elliot – take their place in front of a small stage in this improvised performance space. It’s really nothing more than a storefront, a small warehouse. Trent Thomas started as a musician, but he now works day-to-day maintaining the club.

“The fortunate thing about Birmingham is that we’ve always had somebody who was willing to go out on a limb and rent you know a building somewhere and have shows in it for however long they were able to sustain it. But unfortunately they were doing it in a way in a way that wasn’t really conducive to well, keeping the doors open.”

The overhead expenses are high for nightclubs, and Thomas says punk rock venues would often close in 4 or 5 months. Not even the length of a typical building lease. So when they opened Cave9, they wanted to do things differently.

“The legal name is “The Cave9 music and arts project.”

It may seem like a weird concept – a non-profit nightclub, with indy rock and punk bands. But it’s actually not all that unusual. There are a handful of similar clubs in other big cities like Boston and Seattle. Some are run by school districts, others by church groups. But Cave9 was started by a bunch of friends who wanted a place to gather to talk about art, to host skill shares – like free knitting and music lessons – and most importantly, to listen to music they can’t hear at other clubs.

“That’s the thing, if you want to make money in Birmingham you learn some Lynard Skynard and some Allman Brothers. Seriously, you can make a ton of money doing that. And trust me, I have been tempted to do that many times. The other places have a very specific profit motive. Whereas we’re nonprofit. We’re here specifically to serve the bands. We’re not here to serve alcohol. You know we’re not looking to book bands that will increase our bar tab.”

There is another business in town booking the same kinds of bands as Cave9. BottleTree Cafe is Merrillee Challis’s baby, inspired by years spent in Europe. After college, Challis bought a one-way ticket to Prague and within 3 days got a job at a cafe that was also a bar and a music venue.

“You know it was a very exciting time to be there. It was full of people from all over the place. And there were no restrictions. I was living without a work visa and so was everyone else. It was just kind of this time where lots of magic happened.”

Challis wanted to bring that magic back to Alabama, and after years of planning and saving money, she opened BottleTree 18 months ago. It was and continues to be a huge financial risk.

“It’s really staggering and it keeps me up at night. It’s really stressful. We knew it was a gamble. We knew it would be hard. But I, myself, am very stubborn and it’s hard to talk me out of doing something that I want to do!”

Challis is an artist, but has had to learn the ins and outs of running a for-profit business, a bar-slash-cafe-slash-music venue that has high overhead expenses and sometimes has a hard time attracting audiences.

In the business world there’s an often unspoken rivalry between non-profits and for-profits. One official at the United Way talks about the YMCA being in direct competition with Gold’s Gym, for instance. There are also rumors that pit BottleTree against Cave9… but Marrilee Challis dismisses that idea.

“I think Cave9 definitely specializes in more the punk rock, DIY aesthetic. Usually the bands we’re courting and getting are on labels and have agents, so I think the bands have sort of made it to the next level, quote, unquote. My philosophy is we’re all in this together and we all are parts, very essentially parts of this puzzle for Birmingham to work.”

“I think we compliment each other pretty well,” says Aaron Hamilton, who co-founded Cave9.

Hamilton says his club and Bottle Tree share a common goal: supporting independent music. But there’s no denying nonprofits do enjoy certain advantages over for-profits. Their mailing and advertising rates are often lower. They can apply for grants from foundations and government agencies. They can also accept tax-free donations and are, themselves, exempt from state and local income, property, sales, and excise taxes. But Hamilton says it’s really not that much of an advantage.

“It’s nice to not have to pay tons of taxes, but we’re not really making any money to pay taxes. You know the only money we do bring in is from the door and that usually goes to pay touring bands or pay for equipment or something like that. And you know you don’t get a ton of money like that. We take money at the door, most of the time, but if someone shows up and they don’t have money we let them in more often than not.”

Not exactly a standard business model – for a for-profit or a not-for-profit. Hamilton admits Cave9 is still learning to navigate this whole non-profit nightclub business. And it’s had some hard knocks along the way. Early on, the state of Alabama audited Cave9 and determined it was making more money than it reported on its tax return. The club is still working off a six-thousand dollar tax bill. That’s a whole lot of George Washington’s at the door.

US military used laser to take down Border Protection drone, lawmakers say

The U.S. military used a laser to shoot down a Customs and Border Protection drone, members of Congress said Thursday, and the Federal Aviation Administration responded by closing more airspace near El Paso, Texas.

Deadline looms as Anthropic rejects Pentagon demands it remove AI safeguards

The Defense Department has been feuding with Anthropic over military uses of its artificial intelligence tools. At stake are hundreds of millions of dollars in contracts and access to some of the most advanced AI on the planet.

Pakistan’s defense minister says that there is now ‘open war’ with Afghanistan after latest strikes

Pakistan's defense minister said that his country ran out of "patience" and considers that there is now an "open war" with Afghanistan, after both countries launched strikes following an Afghan cross-border attack.

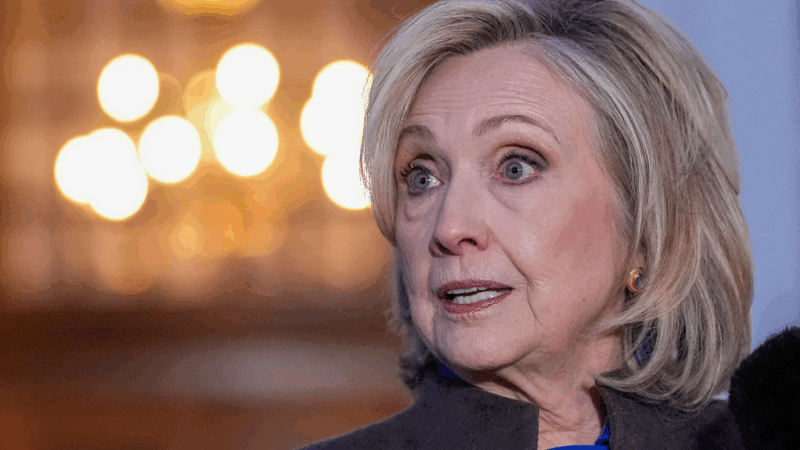

Hillary Clinton calls House Oversight questioning ‘repetitive’ in 6 hour deposition

In more than seven hours behind closed doors, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton answered questions from the House Oversight Committee as it investigates Jeffrey Epstein.

Chicagoans pay respects to Jesse Jackson as cross-country memorial services begin

Memorial services for the Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr. to honor his long civil rights legacy begin in Chicago. Events will also take place in Washington, D.C., and South Carolina, where he was born and began his activism.

In reversal, Warner Bros. jilts Netflix for Paramount

Warner Bros. says Paramount's sweetened bid to buy the whole company is "superior" to an $83 billion deal it struck with Netflix for just its streaming services, studios, and intellectual property.