Urban Divide: Housing

–In our Urban Divide series this week we’ve heard about how Birmingham is losing population, especially young professionals, and how the schools are bleeding students. More than a thousand students leave Birmingham city schools each year and that means fewer tax dollars for education. Ask anyone who follows these trends — say, someone like Alabama Congressman Artur Davis — what’s at the core of the problem and you’ll likely hear “housing”.

In the late 1990’s the federal government determined there were at least 80-thousand public housing units nationwide that were so dilapidated they weren’t fit for human habitation. The government funneled hundred of millions of dollars into tearing down old housing projects and putting up new, shiny multi-family “homes”. In Birmingham, that project is called “Park Place”, but as as WBHM’s Tanya Ott reports, the results have been mixed.

Park Place sits on the northern edge of downtown. If you’re driving up Highway 31 towards 20-59, look over your left shoulder and you’ll see the collection of well-maintained townhouses snuggled between the highway and the skyscrapers. It looks like a complex you’d see in Hoover or Gardendale, but this is a unique social experiment — at least that’s how some observers see it. Forty percent of the units are rented at fair-market prices to professionals and business folks. Another 20 percent of the units are earmarked for people who qualify for low-income housing credits. And the remaining 40 percent go to very low-income residents – folks who’d normally live in “the projects”.

It’s Monday afternoon and despite temperatures peaking at 103 degrees, Park Place hosts an open house. Hot dogs sizzle on the grill as resident Earline Jones lists the many amenities that make this one of the best places she’s ever lived.

“I have a dishwasher, I have garbage disposal, I have a refrigerator with an ice maker…”

What Jones doesn’t have in Park Place are all the nuisances she dealt with while living in another, older housing project in north Birmingham.

“It was noisy and people would shoot guns and police was patrolling all the time for trouble. They were breaking into apartments and getting caught in apartments. The grounds wasn’t kept good like they are here.”

No one disputes that Park Place is nicer than the projects it replaced – Metropolitan Gardens. Metro, as it’s known, was a barracks-style compound. It was crime ridden. Park Place has rules that are changing not just the geography but the psychology of the community. Jaundalynn Givan is the HOPE VI Coordinator for the Birmingham Housing Authority.

“I can’t have people coming now to live with me and staying with me every day of the month. I cannot have a child that’s suspended from school or there are issues that come up where he may not be in school. I may not be able to live on site without maintaining employment.”

But, Metro could house more than 900 families. When all phases of construction are complete, Park Place will have about 600 units total, of all income levels. Critics wonder what happened to the hundreds, maybe thousands, of people who were displaced in the HOPE VI transition.

“You can walk down to Park Place now and see what a beautiful exhibition of downtown living it is, but it’s like building a castle on top of a cemetery. You know, you can’t see the bodies. You love the castle, but the bodies are hidden.”

Scott Douglas, Executive Director of Greater Birmingham Ministries, thinks “the bodies” have been dispersed to low-rent houses run by slum landlords and other less desirable public housing projects, like this one, just across the railroad tracks from Park Place. It’s called Kingston, and it’s the project that hardly anyone requests to live in.

“The lack of affordable supermarket that has diverse supply of groceries and other family needs. The lack of a vibrant neighborhood center. This place is also surrounded by industrial plants and we still don’t know yet what type of pollution is being put out in this neighborhood.”

Many of the units are boarded up, awaiting asbestos and lead abatement treatment. But some residents continue live here while men in white hazard suits do their work. Douglas says the renovation has been going on for at least two years and he doesn’t see any end in sight.

Short of homelessness, this is the bottom of the housing food chain and that makes it susceptible to every housing hiccup that happens up-line. Things like Metro Gardens residents being displaced by HOPE VI and even the recent sub-prime mortgage crisis that’s affecting housing stock all over the economic spectrum. Folks who work to pull themselves out of public housing and look for private housing find themselves competing with those who’ve lost their homes to foreclosure. The Birmingham Urban League, which does home buyer education, says it’s seen a noticeable up-tick in frantic calls from people who are losing their homes. Serita Jackson Womack is the Urban League’s housing director.

“Some of them we counsel over the phone, some will come in for assistance, some may have waited too late to come in, some will call us a day before the foreclosure sale and our hands are tied as to what we can do within 24 hours to help someone get out of a foreclosure.”

UAB sociologist Mark LaGory writes about what he calls the housing vacancy chain in his book “Unhealthy Places.”

“What happens in that vacancy chain is that those at the bottom of that are the poorest and they’re getting the housing that is the least desirable, the oldest, the more difficult to maintain in neighborhoods that are often times deteriorating.”

So they’re getting housing, but it’s housing that’s less likely to appreciate over time. In short, the people who can least afford it are more likely to get a bad investment. LaGory points to Woodlawn as a perfect example.

“I know people who grew up in Woodlawn and who said, you know I’ve taken my parents by the old neighborhood and they’ve shook their heads and said isn’t it a shame this happened to the old neighborhood. And the implication of that is that somehow it’s the people’s fault who moved into those houses and didn’t take care of them.”

LaGory and others argue while HOPE VI and other ambitious projects may turn things around for a small number of individuals, real progress in the housing market here in Birmingham can only come through a concerted effort that bridges government and the private sector. Democratic Congressman Artur Davis agrees.

“There will always be pockets of cities that are not livable. But we’ve got to find ways to reduce those pockets and to create as much attractive living space for people of all income levels. Because it becomes a cycle – if you have a blighted area you get more blight. You have more economic distress develop around it. similarly if you can tur the corner and build attractive living spaces it makes it easier for retail shops to locate there. It makes it easier for other developers to look at the community. We’ve got to figure a way to stay on the positive side of that curve.”

“Until you bring the amenities downtown the people will not come.”

Again, HOPE VI coordinator Juandalynn Givan.

“Some will come, just as they are doing. But if I have to live downtown and still drive to Hoover to get to a major department store that’s not just open Monday through Friday and it shuts down at normal business hours at 5 o’clock – I’m not coming!”

So it’s the classic chicken and egg scenario: it’s hard to get people to move downtown and to other blighted areas of Birmingham if basic services like drug stores and supermarkets aren’t nearby. But developers aren’t willing to bank on promises that if they build it – people will come. It’s a vicious cycle some Birmingham residents know all too well.

Kalshi reveals insider trading case against editor for MrBeast

With prediction markets booming, so have concerns about insider trading. Now, Kalshi has disclosed its first public actions against accounts suspected of trading on confidential information.

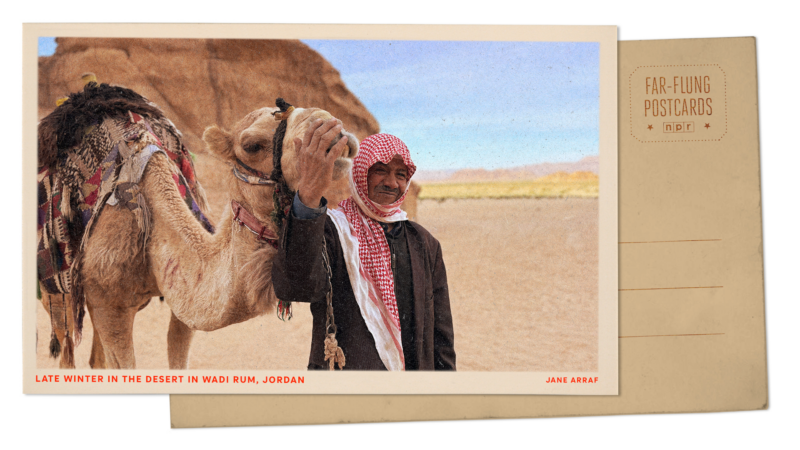

Greetings from Jordan’s Wadi Rum desert, where patches of green emerge after winter rains

Wadi Rum's otherworldly landscape is where Star Wars movies and The Martian were filmed. In late winter, plants emerge in this desert — but some are toxic to camels, so their herders must protect them.

Lack of transportation keeps many Alabamians from working. Rural public transit programs are trying to help

While lack of transportation is a major employment barrier in Alabama, few people take public transit to work. That dynamic is even more pronounced in rural areas.

When a horse whinnies, there’s more than meets the ear

A new study finds that horse whinnies are made of both a high and a low frequency, generated by different parts of the vocal tract. The two-tone sound may help horses convey more complex information.

Hundreds of American nurses choose Canada over the U.S. under Trump

More than 1,000 American nurses have successfully applied for licensure in British Columbia since April, a massive increase over prior years.

Trump’s many tariff tools mean consumer prices won’t go down, analysts say

The Supreme Court struck down President Trump's signature tariffs. But the president has other tariff tools, and consumers shouldn't expect cheaper prices anytime soon, economists say.