SFS: Broken Windows

Birmingham–When Wade Lamar moved to Birmingham’s Enon Ridge community, just northwest of Malfunction Junction, in the mid-1970’s it was a well-kept, working class neighborhood where folks took pride in their homes. But standing in front of his meticulously manicured rose bush, Lamar looks in dismay at what the neighborhood has become.

Birmingham–When Wade Lamar moved to Birmingham’s Enon Ridge community, just northwest of Malfunction Junction, in the mid-1970’s it was a well-kept, working class neighborhood where folks took pride in their homes. But standing in front of his meticulously manicured rose bush, Lamar looks in dismay at what the neighborhood has become.

“Not there’s two ladies in this house right here and they keep their houses up. But the house next to that one, nobody in it, the house across the street there, nobody in it. So the houses go down and the kids don’t keep it up.”

There are overgrown lots, lots of trash, partially burned buildings and worse.

“These vacant properties are havens for drug activities or for illegal sex or rape or child molestation. So they become not only an eyesore, but they also become places of criminal behavior.”

That’s Carole Smitherman, president of the Birmingham City Council. She’s prosecuted lots of cases of street crime and says she’s a firm believer that cleaning up the streets physically will clean up the streets metaphorically. She’s seen it in her own district, just west of UAB.

That’s Carole Smitherman, president of the Birmingham City Council. She’s prosecuted lots of cases of street crime and says she’s a firm believer that cleaning up the streets physically will clean up the streets metaphorically. She’s seen it in her own district, just west of UAB.

“When we went in to clean we saw cigarette papers, beer and wine bottles all in different places where people would stand. So we were able to report that to the police and tell them where we were seeing that kind of trash and so they started riding through more and that started breaking up a lot of those groups that would be standing out loitering.”

That’s the premise behind Birmingham’s new “23 in Twenty-three” clean-up. The so-called “Broken Window Theory”, that one broken window leads to more broken windows, which leads to abandoned cars, overgrown lots, low-level crime like panhandling, gambling and prostitution, and so on. UAB sociology chairman Mark LaGory wrote a book called “Unhealthy Places.”

“There’s high crime, there’s distrust, there is constant danger and fear and therefore people themselves in those communities often times don’t take care of the property and so this becomes a sort of symbol of the pathology that exists in the neighborhood.”

“There’s high crime, there’s distrust, there is constant danger and fear and therefore people themselves in those communities often times don’t take care of the property and so this becomes a sort of symbol of the pathology that exists in the neighborhood.”

Take care of the Broken Windows and crime goes down. At least that’s the theory. In the 1990’s former New York City Police Commissioner William Bratton achieved rock star status by preaching the gospel of Broken Windows.

“You had about three or four years there where crime in New York literally went through the floor and Bratton said, “See, it works!”

John Sloan is chair of the UAB Department of Criminal Justice.

“There�s a big but!”

By the 90’s crime rates were already going down because the crack wars of the 80’s were over and there was a sharp decline in the supply of illegal weapons. Sloan calls these “confounding factors”.

“In effect, you already had something that was occurring naturally. You then implement this thing and then say, well crime went down. But wait a minute, crime was going down anyway before you did this, so can you really say that this was the thing that made the difference? And you can�t.”

“But can you say that it�s not?”

“Well, you can.”

Sloan says while basic evaluations suggest Broken Windows works, more sophisticated analyses don’t.

“I am convinced at this point, based on the empirical evidence that I have seen, that Broken Window policing, by itself, is not the magic bullet that a lot of people, both politicians and police officials believe that it was.”

Still, crews are out on the streets before six in the morning, working at a feverish pitch.

“This is day 7 and there’ll be 16 more days after this and then we start over.”

Don Lupo directs the Mayor’s Office of Citizen’s Assistance. He says the “23 in Twenty-three” effort doesn’t cost the city more money. The crews would already being doing this work, just in a much more scattered fashion. Instead, the 300-plus crew members are now dive-bombing into a specific community on a specific day and doing massive cleanup.

“What we’re looking for, the moral of the story to be, that once we get back to number one that it will be easier and every time we make the swing through it’ll just be that much easier.”

But it’s not easy. The city often runs up against the law, especially when it comes to condemning decrepit buildings.

“This is a marvelous example of what needs to come down.”

Lupo pulls his hulking white pick-up in front of a house in the Smithfield community. The porch has fallen off. There’s no grass in the yard and handwritten signs are tacked to just about every available surface. Lupo says the city recently had to kick 22 dogs out of this home, which is owned and occupied by a man who attended Samford University with Lupo.

“He is a Vietnam veteran and when he’s on his medication he is okay, but when he gets off his medication this is what happens.”

The city has been trying for almost a decade to condemn the house and tear it down, but it’s a long process.

“When someone finds out that their property has been condemned they automatically rush down to city hall and apply for a building permit and once they attain a building permit the demolition process stops. Nine times out of 10 they don’t do a rip-roaring thing, so we are sitting there with a house that needs to be torn down but we can’t tear it down because they have a building permit. They get the building permit, they don’t do anything. But the condemnation process has to start over.”

Scott Douglas knows how difficult it is to clean up worn down communities. As executive director of Greater Birmingham Ministries he’s watched what’s happened to parts of the city.

“Neighborhoods are like houses. You know if a house is not lived in, it could be in Mountain Brook, but if it’s not lived in, it’s going to deteriorate. Houses love company, so do neighborhoods. We once did a neighborhood survey over in north Birmingham and we asked this one particular woman � that’s where it’s plagued by vacant lots � and we asked this open-ended question, what would it take make this a better neighborhood? And you know what she said? More neighbors! She’s surrounded by vacant lots and industrial plants. That neighborhood’s gone. It’s almost irreversible, without tremendous re-investment.”

But who should pay for that “re-investment?” Some critics question why Birmingham is spending time and money cleaning up what, in many cases, is private property. Again, Citizen’s Assistance Director Don Lupo.

“We shouldn’t have to take care of somebody’s private property, but then on the other hand we can’t just allow the neighborhoods to go to seed! We put the lien against the property and eventually get our money back.”

“Do you always get the money back?”

“No. A lot of times we don’t get the money back and if you looked at the books at how much money is owed to use for this kind of work it would be staggering.”

Back in Enon Ridge, Wade Lamar says it’s ironic the city’s putting so much effort into cleaning up trash and weed whacking grass, when he’s been trying for months to get them to cut back nearby trees that threaten power lines.

“Cause one day them wires, gonna go around them wires, and it might cause a big problem for my house and the house down there next to me.”

Lamar notes his neighbors are aging, and he’s not confident their kids will keep up the properties, so he hopes the city sponsored cleanup continue.

— Tanya Ott, December 11, 2007

‘Songs from the Hole’: The story behind JJ’88’s documentary and visual album

The visual album and documentary Songs from the Hole tells the story of James Jacobs, the hip-hop artist JJ'88, as he reflects on his coming-of-age within California's state prison system.

Oil price surges as Iran steps up attacks on ships in the Persian Gulf

Markets seesawed on Day 13 of the war in the Middle East, as two oil tankers were struck by projectiles near Iraq's southern ports and attacks between Israel and Hezbollah intensified.

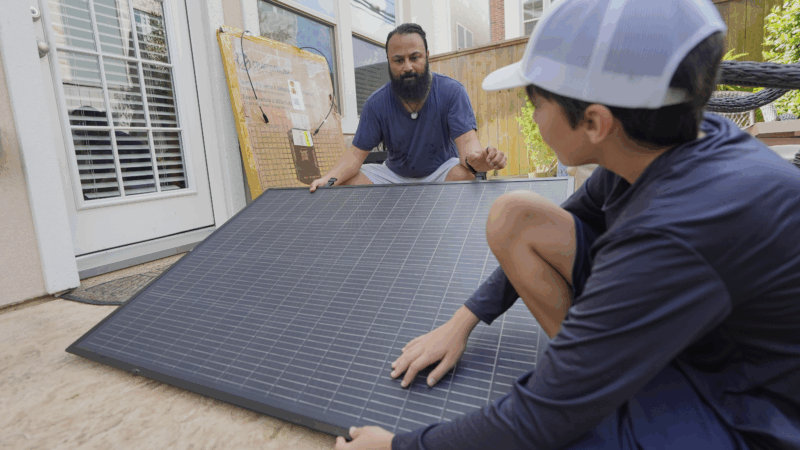

Easy-to-use solar panels are coming, but utilities are trying to delay them

Utilities are convincing lawmakers around the U.S. to delay bills that would allow people to buy solar panels, plug them into an outlet and begin generating electricity.

The Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrant truckers shifts into higher gear

The White House wants tougher rules for commercial licenses after several high-profile crashes involving foreign-born drivers. But critics say that would do little to make the nation's roads safer.

Trump’s war with Iran is angering some swing voters who want money spent at home

Swing voters who helped reelect President Trump in 2024 don't support his decision to go to war in Iran and instead want to see U.S. tax dollars spent tackling economic pressures facing Americans.

5 ways to resist the urge to keep looking at your phone

So you want to spend less time on your phone. How do you do that when it's designed to suck you in? Life Kit spoke to experts in behavioral science, psychology and technology for real-world advice.