Hurricane Katrina: Asian-American’s Mental Health

The Bayou La Batre Church of Christ has become the unofficial town center since hurricane Katrina. The church helps find people everything from food to shelter. Linda Lee has been coming to the church since the storm, and right now she’s rummaging through piles of second hand clothes in the church parking lot. She swoops down on each pile like a hawk, zeroing in on the sweater or t-shirt her family needs. Linda says she’s always moving this fast, and rarely has that moment to breathe.

“And when I do, it’s gotta be house work or something else. It’s driving me crazy.”

(reporter)”And part of what gives you some sanity is working. You equate working with happiness?”

“Yeah, once I get work. Get back on my feet.”

(reporter) “Do you have time to look for work?”

“Not really, cause I take care of my kids.”

Linda’s family lost almost everything in Hurricane Katrina. And it seems that a babysitter for the kids while she looks for work could be a huge help. In the scope of the mental health spectrum, that’s a small thing really. But getting Linda, and others in the South Alabama Asian community, hooked up with those services has been challenging. That’s the job of crisis counselors, and over and over again they say there are two big barriers: language and culture. Perhaps no other single story highlights that better than this one from Lacy Broadus, of Catholic social services. She says after the storm, the demand in the community was for necessities.

“Food clothing, pretty much everything. For some reason, after the storm, everyone wanted their utility bills to be paid. And I don’t know if they thought that was going to delay the power being turned back on because their utility bills were delinquent. So we paid a vast amount of utility bills right after the storm.”

When the lights finally came back on, Broadus moved on to her main mission: referrals to long term mental health care and other services. The idea is to give people -that want it- the support they need to help get through rocky times. So, Broadus started passing around sign up sheets for counseling services. And immediately, the response was surprisingly overwhelming.

“And so I started going and doing home visits, and started basing the needs based on priority. If you were elderly, if you were disabled if you had medical conditions. If you had small children.”

But door to door work is time consuming, and soon, Broadus says, many in the Asian community got impatient. They would come back to the tent headquarters, filling out more applications for mental health services.

“Even several days later, come to find out they were coming back and you know-you already filled out an application three days ago.”

Turns out the applications for mental health services looked similar to the other applications for material and FEMA aid.

“They may not have been even have been aware of what they filled out and didn’t realize exactly what services they were applying for.”

Meaning that big demand in the Asian Community for help was really just a big misunderstanding. Soon more translators were available, but then word got around the community that the tent was for mental health services, and then people stopped coming around. Broadus describes it as a frustrating situation for everyone, and soon, Catholic Social Services pulled out of Bayou La Batre. But they were quickly followed by Project Rebound.

“Here’s a home with trailers in front of them…”

That’s Alicia Richardson. She runs Project Rebound, and right now she’s driving the south Alabama neighborhoods her program serves.

“But it’s our goal to find people and let them know what resources are there and available in an effort to help them restore and rebuild their lives.”

Project Rebound takes a no-pressure approach to crisis counseling. Richardson says that’s an important part of establishing trust with potential but hesitant clients.

“One of the things we have to be very careful about is telling someone-you need some help! Because someone who is already in distress doesn’t want you to tell them they’re crazy.”

Overall, Richardson says her team is having tremendous success. They’ve referred more than 4,000 area residents. But it’s not clear how successful Project Rebound has been in the Asian community. To avoid the appearance of quota tracking, the federally-funded program doesn’t keep statistics based on ethnicity or race. And when pressed, Richardson acknowledges her group has been challenged by language and cultural barriers. But Richardson also notes that most people, regardless of ethnicity, handle life after a disaster in their own way.

“Everybody that goes through a disaster does not need psychological services. Because by nature, we are resilient. People are resilient. They have the ability to bounce back. Given the right support.”

And to encourage people to accept that support, the region’s mental health groups are informally coordinating their services. The hope is that through a constant presence trust can be established with the community. But Richardson says service providers also don’t want to have too big of a presence.

“You don’t want five and six teams of people knocking on the same door, when you have other areas that have damage as well and they don’t have anybody knocking on their door.”

But when they knock, will someone answer? Back at the church of Christ, Linda Lee, answers that question with a resounding no. She says talking to someone, even about her immediate problems, would mean thinking about everything that’s gone wrong since Katrina.

“And I don’t want to think about it again. What’s gone is gone. And I just don’t want to talk about it.”

And despite anecdotal evidence that suggests domestic violence and alcoholism has increased in the community since Hurricane Katrina, Lacy Broadus of Catholic Social Services says most Asian Americans won’t seek or accept mental health help.

“I haven’t had one family in the Asian community that was in need of mental health or counseling or had prior mental health counseling needs. Or had prior mental health or counseling needs. And that’s just from my assessment.”

So when Catholic Social Services and Project Rebound both make plans to go back into the community to try outreach again, it begs the question – Why? Why keep knocking on those doors when it seems the answer is no time and again?

“There may be that one that says yes, I’m interested in it. I may see some areas of clinical therapy they may need. But I have to let them make that call on their own. I just let them know the services are available if they’re interested. It’s a slow process, but it’s coming along.”

Broadus says reaching the community is important enough to keep her chipping away at those cultural and language barriers, even if Hurricane Katrina couldn’t tear them down.

‘Songs from the Hole’: The story behind JJ’88’s documentary and visual album

The visual album and documentary Songs from the Hole tells the story of James Jacobs, the hip-hop artist JJ'88, as he reflects on his coming-of-age within California's state prison system.

Oil price surges as Iran steps up attacks on ships in the Persian Gulf

Markets seesawed on Day 13 of the war in the Middle East, as two oil tankers were struck by projectiles near Iraq's southern ports and attacks between Israel and Hezbollah intensified.

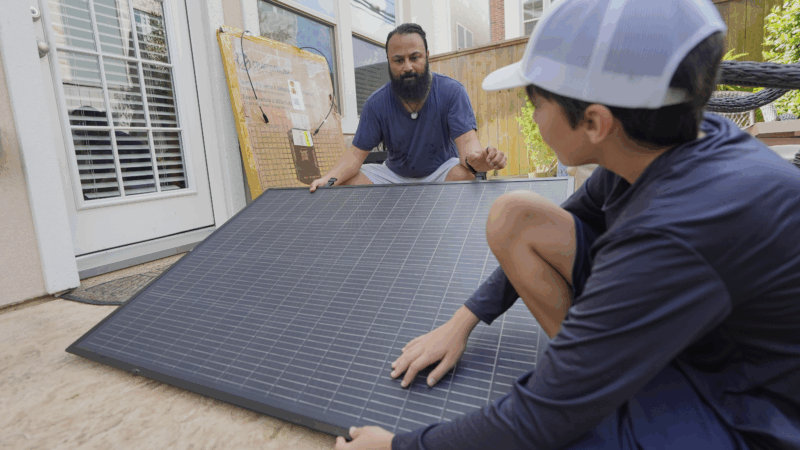

Easy-to-use solar panels are coming, but utilities are trying to delay them

Utilities are convincing lawmakers around the U.S. to delay bills that would allow people to buy solar panels, plug them into an outlet and begin generating electricity.

The Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrant truckers shifts into higher gear

The White House wants tougher rules for commercial licenses after several high-profile crashes involving foreign-born drivers. But critics say that would do little to make the nation's roads safer.

Trump’s war with Iran is angering some swing voters who want money spent at home

Swing voters who helped reelect President Trump in 2024 don't support his decision to go to war in Iran and instead want to see U.S. tax dollars spent tackling economic pressures facing Americans.

5 ways to resist the urge to keep looking at your phone

So you want to spend less time on your phone. How do you do that when it's designed to suck you in? Life Kit spoke to experts in behavioral science, psychology and technology for real-world advice.