Why are people freaking out about the birth rate?

There’s one little statistic that seems to have gained a lot of attention recently: the birth rate. It’s been in decline for a while, and is currently below the level of replacement. With pronatalist ideas showing up in our culture and politics, Brittany wanted to know: why are people freaking out? Who’s trying to solve the population equation, and how? Brittany is joined by Kelsey Piper, senior writer at Vox, and Gideon Lewis-Kraus, staff writer at The New Yorker, to get into how the birth rate touches every part of our culture – and why we might need to rethink our approach to this stat.

Interview highlights

Is birth rate decline a real problem? What issues might it cause?

KELSEY PIPER: A lot of the way the economy is set up, institutions like Social Security, they were built when we had a growing population. And they do have a sort of assumption baked into them that there will be enough people who are working age to support [retired people]. [If] we don’t have as many working people, then that ratio gets very unbalanced.

GIDEON LEWIS-KRAUS: One of the problems of a shrinking and aging population is almost certainly going to be even greater political instability. As there are fewer people, the economy shrinks, there’s less to go around. We are actually almost certainly going to see a rise in inequality. In South Korea right now, they don’t have enough bus drivers. And so the first things that are going to disappear are public bus routes that people rely on. And as there are fewer and fewer teachers, there’s going to be shifts into private education. If you’re not careful about the distributional aspects of this, you’re going to end up with an increasingly unequal society.

PIPER: [Also], in cultures where children are very rare, the confidence and feeling that you can have children, that that is an available life path such that people go down, [it] becomes less viable in a bunch of ways – like, are there parks? Are people accepting of children in public? Is it a normal thing to do? That has a huge impact.

It seems there are a few camps trying to solve the population equation: liberal pro-natalists, conservative pro-natalists, and even people who support population decline. How are they all approaching this issue?

LEWIS-KRAUS: So there’s a kind of liberal instinct that says, ‘okay, the fertility decline is not a problem in and of itself, but it’s a symptom of other underlying problems. It’s a symptom of how degraded our social services are, the fact that we have no robust social safety net, and if you had a much better welfare state, these things would naturally go away.’ Now, for a long time, the Scandinavian countries presented a kind of an emergency brake – that if things got bad enough, we could all switch to Nordic affordances for parental leave and child care subsidies. But then [Scandinavian birth rates] fell off a cliff, too.

There are traditional conservative pronatalists, and there are also more tech-oriented pronatalists, but it seems like these groups have a kind of alliance. How are they approaching raising the birth rate, and what’s their alliance built on?

LEWIS-KRAUS: One thing that a technological pronatalist told me – he said, ‘look, I understand the nature of the divisions that my camp has with the more traditional wing of this coalition, but both of us have greater aspirations for like what makes a human life meaningful and significant than just retiring to the villages in Florida.’ [But] it seems like an unstable coalition. Actually, an insistence on a return to patriarchal traditionalism – it doesn’t work. There are plenty of places in the world like Tunisia or Iran, where along various dimensions, these are plenty traditional societies where we have also seen a radical fall [in birth rates]. The other thing is [these camps] do have very different underlying views on reproductive technologies. There are people in that [technological pronatalist] movement who think the solutions are going to be much better and more viable IVF, and then this idea that in 20 or 30 years we’ll have artificial wombs. And those are things it’s very hard to imagine traditionalist pronatalists getting on board with.

What about people who welcome population decline for environmental reasons?

PIPER: So I’m going to mention just briefly, a lot of “kids are bad for the climate” stuff basically assumes that there will be no further progress on green energy, that what we have now is the best it’ll ever get, and that for those kids’ entire lives, they will be emitting carbon at exactly the level of a current American. It’s just a very pessimistic worldview, right? Also, our per capita emissions are declining in the United States. And then the other thing is we did so much environmental damage when there were a billion humans on the world. What effects people have on the environment is partly a product of how many there are, but it’s also a product of our knowledge, our scientific understanding of the world, our state capacity, our ability to follow up on what we do know. We can protect the national parks when we have a wealthy, non bankrupt state that cares about the national parks. We can protect endangered species when we can train lots of biologists who can identify endangered species and figure out what protections they need.

What does all this thinking about the birth rate say about how we’re thinking through the future of humanity?

LEWIS-KRAUS: Maybe the last thing that we want to do is freight children with even greater of a symbolic role in our discourse. The worst possible outcome here is that we allow this to become a full blown culture war thing. Maybe what we want to do is wean ourselves of the habit of talking about children in symbolic terms, as far as what they reflect about our identity, and instead, try to remember that children are actually just little people who maybe could be taken on their own terms.

Transcript:

BRITTANY LUSE, HOST:

Hello, hello. I’m Brittany Luse, and you’re listening to IT’S BEEN A MINUTE from NPR, a show about what’s going on in culture and why it doesn’t happen by accident.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

LUSE: There’s one little statistic that I’ve been hearing about constantly, and I’m sure you have, too – the birth rate.

(SOUNDBITE OF MONTAGE)

KRISTI KRUEGER: Women in the United States are still having fewer babies than usual. The number of children women have, a metric known as the fertility rate, has been dropping since the year 2008.

VICE PRESIDENT JD VANCE: I want more babies in the United States of America.

ELON MUSK: The birth rate is very low in almost every country. America had the lowest birth rate, I believe, ever. That was last year. And nothing seems to be turning that around. Humanity is dying.

LUSE: The number of kids each person needs to have to sustain the population is two. The U.S. birth rate? It’s around 1.6. I’ve seen so many think pieces arguing about what we should do about it, and angst about our birth rate has become part of our politics. Trump has called himself the, quote, “fertilization president.” He’s floated the idea of cash bonuses for new babies and even directed the Department of Transportation to give more money to areas with higher fertility rates. And I’m like, whoa, OK, I already get enough pressure to have kids, but I never imagined that that pressure would come from the government, too. And I’ve been kind of confused about all this because for a long time, all I heard was that there were too many people on the planet.

KELSEY PIPER: Everybody sort of assumed birth rates will stay high, and they didn’t.

LUSE: That’s Kelsey Piper, senior writer at Vox.

PIPER: And so that means that almost all of our thinking about what the big challenges of the next century were going to be in terms of population were just completely wrong.

LUSE: But why would a lower population be a problem? Who’s trying to solve for this, and how? And why is there so much cultural pressure now on fertility rates? This is Your Body, Whose Choice? And for the past few weeks, we’ve been looking at the cultural, legal and ideological framework shaping reproductive health in America and what this means for the near and far future of our families, our personal agency and our planet. In this final episode, I’m joined by Kelsey Piper, who you just heard…

PIPER: Thanks so much.

LUSE: …And Gideon Lewis-Kraus, staff writer at The New Yorker, where he wrote a huge, in-depth piece on the birth rate.

GIDEON LEWIS-KRAUS: Thank you so much for having us.

LUSE: We’re going to dive into fertility at a macroscale to see how changes in the birth rate touch every part of our culture and lives and why we might need to reframe how we think about this one little stat.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

LUSE: For a long part of history, there has been a lot of fear around overpopulation. Thomas Malthus in 1798 predicted nonstop exponential growth. In the ’60s, there was a very popular book called “The Population Bomb,” which contributed to a panic about population that led to policies in India that forcibly sterilized millions of people and led to the one-child policy in China. Even as recently as 2014 – about 10 years ago, right? – one Pew study found that when asked whether or not the growing world population would be a major problem, 59% of Americans agreed it will strain the planet’s natural resources, while 82% of American scientists they polled said the same. But I feel like we’re getting some very different rhetoric on this today. What’s changed?

LEWIS-KRAUS: Well, I mean, I think this was in the water – this sense that the U.S. was going to be somehow on the hook for global population explosion because it was going to lead to poverty, which was going to lead to communism. So it became, like, a big part of the Cold War. Lyndon Johnson, in the mid-’60s, said, like, look, you know, we in the West actually have to take some responsibility and pay to subsidize population control programs all over the world. But for anybody who was paying close attention, even by the time of “The Population Bomb’s” publication in 1968, the timing was kind of hilarious because population growth had stopped accelerating.

When I first became interested in this subject, I was at a conference four years ago with a bunch of economists who were giving papers on this. I knew basically nothing about it. I mean, that was, like, the very beginning of Americans starting to talk about this at all, even though it had been something that East Asia and parts of Europe had been dealing with for decades. But it really was just, like, not something on our radar at all, in part because we remained in aberration for a long time that our birth rate didn’t start to decline until the Great Recession. And it seemed that, oh, well, at first, this is just a function of the Great Recession. Now it’s just going to bounce back. And then it didn’t bounce back.

LUSE: Yeah.

LEWIS-KRAUS: So it was really only, like, 2020, 2021, when, by that point, the U.S. fertility rate had dropped by about 20% over 15 years that people started to pay attention here. Also, of course, historically, we were a high-immigration society, although it seems to be changing. So there was some part of American exceptionalism and naivete that we thought, like, this just wasn’t going to affect us.

LUSE: This conversation is about family planning and fertility and population, but it’s essentially a big question about how many people there should be on Earth or in our nation, right? And there are a lot of different people trying to solve for this number, and they’re all coming at the population equation with wildly different strategies for how to do that. And I want to focus on how these camps are kind of shaping our culture and politics right now. First, I want to talk about pronatalists – people who want there to be more babies, who want the birth rate to be higher. One of the big arguments that pronatalists make is that not at least meeting the level of replacement will be potentially bad for the economy. What might happen there?

PIPER: A lot of the way the economy is set up, institutions like Social Security – they were built when we had a growing population.

LUSE: Right.

PIPER: And they do have a sort of assumption baked into them that there will be enough people who are working age to support the retirements of people who we, as a society, have made a promise we’re going to support, like, their retirement or whatever. We don’t have as many working people. Then that ratio gets very unbalanced. And then this is also a self-fulfilling spiral because we all know that burdens on young working people are one of the things that stop people from starting families.

LUSE: Right.

PIPER: If they’re having a hard time getting established, getting a home, meeting a partner who has a good job, then they’re less likely to have children.

LEWIS-KRAUS: I just wanted to take Kelsey’s point and direct it toward one of the kind of immediate, intuitive objections you get to talking about this as if it’s a problem, which is that people will tell you, well, but wait a minute. It was only about 50 years ago that the Earth had half as many people as it does today, and, like…

LUSE: Right.

LEWIS-KRAUS: …Things weren’t catastrophic then. Like, so, like, how are things going to be catastrophic in the future? Now, this misses a few different things. Mostly, to Kelsey’s point, what this misses is that the population structure was much different then. Yes, there were half as many people, but there was a far greater share of younger people than the kind of depopulated world that we’re looking to. So it won’t just be a smaller world. It will be a smaller world and a much older one.

PIPER: Yeah.

LEWIS-KRAUS: There’s a whole body of economic literature that suggests that not only is economic growth tied to population growth – what’s important is dynamism and novelty and that, like, it is young people who have new ideas about how to do things.

LUSE: I mean, that’s really something that I feel like has entered our political conversations even over the last year, year and a half, like, as a lot of people have alleged – that we are living in, like, a gerontocracy, meaning that, you know, the U.S. is governed by a lot of seniors.

LEWIS-KRAUS: To take it out of the realm of economics for a minute, one of the problems of a shrinking and aging population is almost certainly going to be even greater political instability. As there are fewer people, the economy shrinks. There’s less to go around. That – like, what’s going to happen is not that there are going to be the same amount of goods and services and just fewer people to consume them. We are actually almost certainly going to see a rise in inequality. In South Korea right now, they don’t have enough bus drivers. And so, like, the first things that are going to disappear are, like, public bus routes that people rely on.

LUSE: Yeah.

LEWIS-KRAUS: And as there are fewer and fewer teachers, there’s going to be, like, shifts into private education. If you’re not careful about the, like, distributional aspects of this, you’re going to end up with a increasingly unequal and probably illiberal society.

LUSE: You know, it’s interesting. I used to work for the city government of Detroit, and one of the things that we were always trying to solve for was how to deal with a city that was physically very large but also had a shrinking population. A lot of what you’re describing about the, you know, possible near future in South Korea reminds me a lot of things that I saw happen in a city – that major city that had been depopulated, you know, like a lack of bus routes, even though one-third of the city, at that time, did not own cars. There was a lack of, like, grocery stores. These are big problems to solve. And that was for a city of, you know, hundreds of thousands of residents. It’s very different when you’re talking about, you know, the scale of a country or a continent or a planet. What are the other cultural impacts we might see from a shrinking population?

PIPER: One thing that stands out to me is that how many kids people have depends a ton on what is normal in their society.

LUSE: Ooh, yeah.

PIPER: Yeah. People look at their neighbors. They look at their friends. They look at their siblings. Some people still choose not to have children, and I’m a hundred percent supportive of that as an individual choice. But in cultures where children are very rare, the confidence and, like, feeling that you can have children, that that is, like, an available life path…

LUSE: Yeah.

PIPER: …Such that people go down that life path, it becomes less viable as a life path in a bunch of ways in terms of, like, are there parks? Are people accepting of children in public? Is it a normal thing to do? It’s a huge impact.

LUSE: I mean, you know, I think the culture is already shifting on that front. Something that comes up a ton – you know, a lot of people are very comfortable sharing their total intolerance for children and children’s behavior, which is, you know, famously not chill. They receive a lot of support and a lot of likes and a lot of comments, a lot of shares. And to that point about family size depending a bit on cultural norms, I’ll say myself, I mean, I’m 37. I don’t have any children yet. And I have a hard time seeing myself having more than one or maybe twins by chance. And I don’t have any friends that have more than two, but I grew up with two siblings. Like, I grew up in a family of five. Over half of women now have just one or two kids, a flip from 1980, when over half of women had three or more.

PIPER: I agree completely. It’s been a generational shift. I have these interactions pretty frequently where I say to people, like, yeah, we have three. We’re trying for our fourth. And they’re like, oh, yeah, you know, I’ve always kind of wanted – but if they don’t see it anywhere around them, they don’t feel like it’s a life they can imagine for themselves.

LUSE: Coming up – the warring visions for raising the birth rate and politics behind them.

LEWIS-KRAUS: The worst possible outcome here is that we allow this to become just, like, a full-blown culture war.

LUSE: Stick around.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

LUSE: OK. So you’ve both identified the potential problems here with the population shrinking. But going back to pronatalists as a group, there are a lot of different ways you can be pronatalist. Let’s start with the liberal pronatalists. How are they approaching raising the birth rate?

LEWIS-KRAUS: So there’s a kind of liberal instinct that says, like, OK, the fertility decline is not a problem in and of itself, but it’s a symptom of other underlying problems. And it’s a symptom of how degraded our social services are, the fact that we have no robust social safety net, and that actually, if you had, like, a much better welfare state, like, these things would naturally go away. Now, for a long time, the Scandinavian countries presented a kind of, like, in-emergency-break-glass that, like, if things got bad enough, we could all, like, switch to, you know, Nordic affordances for parental leave and child care subsidies and all sorts of things. But then…

LUSE: Yeah.

LEWIS-KRAUS: …Those fell off a cliff, too. And so that took away this sense that, like, you can kind of welfare your state out of this.

LUSE: Wait. When you say those fell off a cliff too, you mean Scandinavian birth rates, just to be clear. Got you.

LEWIS-KRAUS: Yes. It does sound like a wonderful place to be a parent – don’t get me wrong – but it does nothing for the birth rate, although it does seem like maybe there are ways to spend your way out of this. Some of the pronatalist MAGA people have proposed, like, this $5,000 baby bonus, which, like…

LUSE: Yeah.

LEWIS-KRAUS: It doesn’t work. But, you know, if you got something on the order of two or $300,000 per child, like, that really could change a lot.

LUSE: Right. Five thousand dollars covers the average hospital bill for the birth and, like, a month and a half of child care. And, I mean, I guess that’s nice, for sure, but not going to get you very far. But $300,000 – that’s about the average total cost of raising a child into adulthood. That’s subsidizing the whole thing.

LEWIS-KRAUS: But the problem is, that would require, you know, a complete reorientation of our priorities as a society. Right now, we force families to internalize most of the costs of producing productive members of society, and we subsidize them once they’re no longer productive. And that – actually, like, maybe that’s kind of backwards, that, like, maybe we really should be investing way more in, you know, supporting children than we do on the other end of the age distribution. But the problem is, getting there politically seems kind of impossible because it’s old people who vote.

LUSE: Yeah, and old people who govern – yeah. You know, you mentioned, Gideon, the $5,000. That figure has been floated around as something that perhaps maybe the Trump administration might want to start incentivizing having children with $5,000 per child. You know, as I said, I feel like pronatalism is a little stronger on the right. There are traditional conservative pronatalists that might look like JD Vance, whose politics are very focused on traditional family formation. And he said that he wants more babies in the U.S. From them, I think it’s more about a return to religious, quote-unquote, “traditional” family structures.

But there are also more tech-oriented pronatalists – people like Elon Musk, but also Simone and Malcolm Collins, who are also leaders of this movement. The more techie people, I think, tend to use IVF a bit more consistently, in some cases to select for their child’s genetics. And they seem to be in it for supporting the future economy and avoiding what they think will be a civilization collapse. It seems like these groups have a kind of alliance. How are they approaching raising the birth rate, and what’s their alliance built on?

LEWIS-KRAUS: Well, it seems like an unstable coalition. Actually, an insistence on, like, a return to, like, patriarchal traditionalism just – like, is just going to make everything worse.

PIPER: Yes.

LEWIS-KRAUS: There are plenty of places in the world, like Tunisia or Iran or – like, along various dimensions, these are plenty traditional societies where we have also seen, like, a radical fall and that, like, inegalitarianism certainly does not help the cause. It doesn’t work. And so you would hope that, like, the techno wing would notice that.

The other thing is, they do have very different underlying views on reproductive technologies and that, you know, there are people in that movement who think, well, the solutions are going to be, like, much better and more viable IVF, although it’s worth pointing out that, for now, it just doesn’t work as well as people think that it does. Although who knows? It might improve. And then, of course, this idea that, in 20 or 30 years, we’ll have artificial wombs – and those are things where it’s very hard to imagine the, like, traditionalist pronatalists getting on board with.

LUSE: Yeah. I could see that.

LEWIS-KRAUS: One thing that a technological pronatalist told me is that he said, like, look, I understand the nature of the divisions that, like, my camp has with the more traditional wing of this coalition, but both of us have greater aspirations for, like, what makes a human life meaningful and significant than just, like, retiring to The Villages in Florida. That, like, they believe in, like, you know, a kind of, like, divine spark – that, like, human life is sanctified, and, like, that’s the reason that we’re, like, obligated to have kids. And we believe – instead of, like, a divine spark, we believe in the future. For now, those two things have, like, dovetailed.

LUSE: You know, I will say that I think some of the fear around people not wanting kids generally is a little unfounded. According to Gallup, 9 in 10 U.S. adults already have children or would like to have them. And the desire for more kids is already kind of there. Thirty-nine percent of parents have fewer kids than they want. So I think people trying for kids later and having smaller families generally is driving a lot of this change.

But I also want to note there are also zero-population-growth people who want the birth rate to be at replacement level – like, exactly – as well as people not having kids for climate reasons. I think a lot of us remember studies and articles claiming kids are bad for the environment. And 26% of people aged 18 to 49 who say it’s not likely they’ll have kids cite concerns about the environment as a major reason, according to Pew. For people who might welcome the idea of a population decline, how are they approaching this problem?

PIPER: So this is kind of my bugbear, so I’m going to mention just briefly. A lot of kids-are-bad-for-the-climate stuff basically assumes that there will be no further progress on green energy – that what we have now is the best it’ll ever get and that, for those kids’ entire lives, they will be emitting carbon at exactly the level of a current American. It’s just a very pessimistic worldview, right? Also, our per-capita emissions are declining in the United States.

And then the other thing is, we did so much environmental damage when there was a billion humans on the world. What effects people have on the environment is partly a product of how many there are, but it’s also a product of our knowledge, our scientific understanding of the world, our state capacity, our ability to follow up on what we do know. We can protect the national parks when we have a wealthy, non-bankrupt state that cares about the national parks. We can, you know, protect endangered species when we can train lots of biologists who can identify endangered species and figure out what protections they need.

LUSE: You know, we’ve discussed a lot of hypotheticals, right? But also, these population shifts are already happening, and they’re happening at the same time as there’s an assault on reproductive rights – you know, of course, the continued curtailing of abortion rights, which can make having kids less of a choice for women in particular. House Speaker Mike Johnson, for example, blamed abortion for fewer workers in the economy to contribute to Social Security.

Having kids is a really personal, individual decision, and they are a lot of work. Like, even if there are issues that come with a lower birth rate, I would hate to see policies that coerce people into having more. And as we’ve discussed, it seems like the solutions that people have thought of to boost the birth rate are mostly ineffective. Do we actually have control over this, or should we focus more on adapting to a shrinking world?

PIPER: To be clear, I think coercion should be, like, completely or categorically off the table. But if you want to – you know, we’re going to try and do free day care. We’re going to try and do bonuses. We’re going to try and do giveaways. The sooner you start doing that – these things have effects, but they have very small effects.

And if you wait until you have a birth rate of, like, 1.1 or, like, 0.9 and then try and take measures, you’ve already dug yourself a really, really deep hole. So inasmuch as you think we at least want to have a mature conversation about whether we want to take any public policy measures to make family formation easier, it makes sense to do that early. Like, it makes sense not to wait until you have a, like, catastrophically dire situation where there are practically no children.

LEWIS-KRAUS: Well, this was one of the reasons why I went to report my piece in South Korea because the government has tried for the last 20 years anything you can imagine, practically, to raise the fertility rate – from, like, attempts to reform the housing market, towns that have, like, dating events. Like, they’ve kind of tried everything. They’ve spent something on the order of $250 billion, depending on how you do the accounting.

LUSE: Right. And it’s worth mentioning that, in 2024, the birth rate in South Korea rose for the first time in nine years, but from 0.73 to 0.75 births per woman, which – you know, good for them, but that’s still not a lot.

LEWIS-KRAUS: Right. And so one of the things that a lot of demographers and economists said to me when I was in Seoul was, no, actually, we are past the point of attempted remediation – that, like, what we really need to do now is to be adapting to what this looks like because there are different paths ahead of us. And we can try to kind of manage this decline in a way that, like, makes it a little bit more smooth.

Some American demographers will tell you that, like, right now America does not have a problem. America has a fertility rate of 1.6. It is larger than the European average. It’s larger than the OECD average. There’s no reason to panic now. But what happened in a place like South Korea is that, like, they were around 1.6 in, like, the late ’80s, which is where we are now. And then they kind of stabilized for a while, and then they went into this, like, real downward spiral. And, like, a lot of other places where this has happened, like, in Nepal, it’s happened incredibly quickly. Chile – it’s happened incredibly quickly. So, like, we have a very poor imagination for exponential growth. And if that’s true, we have a very poor imagination for exponential decay.

LUSE: You know, I wonder – like, what does all this attention to birth rates in the U.S. say about how we’re trying to think through the future of humanity?

PIPER: I think we would benefit from more of a positive vision of humanity’s future than we have. I have to say, the pronatalist ones currently on offer – either the, like, we, you know, try and solve this all with technology one or the – we try and revert to being a traditional religious culture, which, as Gideon said, emphatically doesn’t work, actually – sexism, like, seems to be correlated with birth rates declining. But that just means that we don’t have a vision there yet, and I’d like to see one. I’d like to see an account of, like, 2100.

I wonder what would happen if we replaced the messages we were all raised with – these messages about there being too many of us, about contributing to an overpopulation problem, about being like, part of a planet that can’t hold us – if we instead said, humans are good. The environmental challenges are going to be solved by young people because of the dynamism that Gideon talked about. I feel like we have yet to try, just saying – discard that message that, like, we should all be a little bit embarrassed to be here – that there’s too many of us.

So I think, at its best, some of the discussion of the future of humanity might let us start to articulate positive visions for the future of humanity. And I don’t want a, like, singular vision. I want, like, lots of competing visions of the many, many cool things that humanity can build in the future.

LEWIS-KRAUS: I agree with everything that Kelsey just said. I will add one other vision of what this looks like, which, in a weird way, is kind of the opposite, which is that maybe the last thing that we want to do is freight children with even greater of a symbolic role in our discourse. And, like, Kelsey wrote very well recently something that I totally agree with, which is, like, the worst possible outcome here is that we allow this to become just, like, a full-blown culture-war thing. Maybe what we want to do is wean ourselves off the habit of talking about children in symbolic terms as far as, like, what they reflect about our identity, what they reflect about our broader feelings about humanity and its future, and instead, like, try to remember that children are actually just little people who, like, maybe could be taken on their own terms.

LUSE: This was really, really, really interesting. Thank you both.

PIPER: Yeah. Thank you so much.

LEWIS-KRAUS: Thank you so much, Brittany, and it was a pleasure to be with you, Kelsey.

LUSE: Thanks again to Kelsey Piper, senior writer at Vox, and Gideon Lewis-Kraus, staff writer at The New Yorker.

This episode of IT’S BEEN A MINUTE was produced by…

LIAM MCBAIN, BYLINE: Liam McBain.

LUSE: This episode was edited by…

NEENA PATHAK, BYLINE: Neena Pathak.

LUSE: Our supervising producer is…

BARTON GIRDWOOD, BYLINE: Barton Girdwood.

LUSE: Our executive producer is…

VERALYN WILLIAMS, BYLINE: Veralyn Williams.

LUSE: Our VP of programming is…

YOLANDA SANGWENI, BYLINE: Yolanda Sangweni.

LUSE: All right. That’s all for this episode of IT’S BEEN A MINUTE from NPR. I’m Brittany Luse. Talk soon.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Top 5 takeaways from the House immigration oversight hearing

The hearing underscored how deeply divided Republicans and Democrats remain on top-level changes to immigration enforcement in the wake of the shootings of two U.S. citizens.

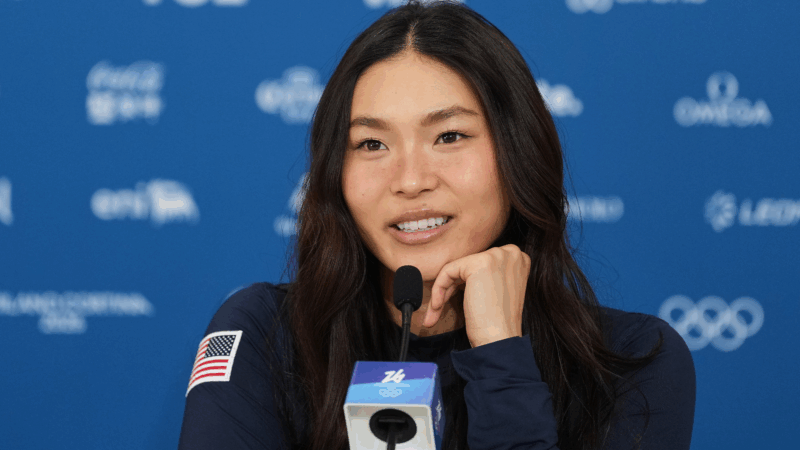

Snowboarder Chloe Kim is chasing an Olympic gold three-peat with a torn labrum

At 25, Chloe Kim could become the first halfpipe snowboarder to win three consecutive Olympic golds.

Pakistan-Afghanistan border closures paralyze trade along a key route

Trucks have been stuck at the closed border since October. Both countries are facing economic losses with no end in sight. The Taliban also banned all Pakistani pharmaceutical imports to Afghanistan.

Malinowski concedes to Mejia in Democratic House special primary in New Jersey

With the race still too close to call, former congressman Tom Malinowski conceded to challenger Analilia Mejia in a Democratic primary to replace the seat vacated by New Jersey Gov. Mikie Sherrill.

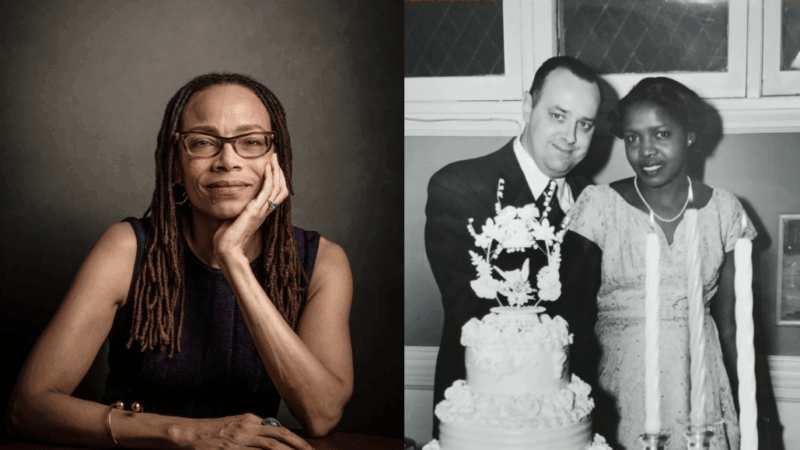

A daughter reexamines her own family story in ‘The Mixed Marriage Project’

Dorothy Roberts' parents, a white anthropologist and a Black woman from Jamaica, spent years interviewing interracial couples in Chicago. Her memoir draws from their records.

FBI release photos and video of potential suspect in Guthrie disappearance

An armed, masked subject was caught on Nancy Guthrie's front doorbell camera one the morning she disappeared.