What the Class of 2025 has to say about the state of higher education

In March, less than three months away from college graduation, Liam Powell received an email from the State Department.

“We regret to inform you that the U.S. Department of State has cancelled the Summer 2025 cycle of the Student Internship Program,” it read. “The Department hereby rescinds your tentative offer to participate in the Student Internship Program.”

The announcement came weeks after President Trump signed an executive order instituting a hiring freeze across the federal workforce, as a part of his effort to reduce what he considers waste and inefficiency in the government.

Powell, a global health and policy major at Duke Kunshan University, Duke’s satellite campus in Suzhou, China, says he wasn’t particularly surprised to see the internship program go.

“Honestly, it was something that I was expecting for a long time,” he says with a sigh. “I just found it really unfortunate that it happened so late.”

This summer, millions of university students are entering an uncertain post-graduation landscape – with the Trump administration’s federal hiring freeze, strained research funding, and the slew of executive orders targeting higher education.

For the Class of 2025, the usual anxieties of life after college now come with added pressure and unpredictability. NPR spoke with three graduating students about how they’ve learned to adapt, move forward and find hope during their final semester of college.

Federal agencies’ hiring freeze led to career pivots

Powell wanted to work for the federal government straight out of college. After his sophomore year, he had a summer internship with the United States Agency for International Development, where he worked in a department that provided services like HIV testing, vaccines and funding for HIV/AIDS research in other countries.

A month after the federal hiring freeze, the Trump administration also made sweeping cuts to USAID, after a review of spending designed to “ensure taxpayer dollars were used to make America stronger, safer, and more prosperous.” The freezing of foreign assistance grants and awards, in turn, resulted in layoffs of thousands of employees.

With these rapid changes on top of his rescinded internship offers, and watching his mentors and former colleagues pack up their desks, Powell says he saw the “writing on the wall,” when it came to his future in international development.

“There’s a feeling that’s pretty selfish, of knowing that the career field that I’ve spent so long studying for in my undergrad is going to be in such a state of flux for a long time,” he says.

“Talking to a lot of professionals that work in the foreign aid and international development sector, there’s a really common perspective that reform is absolutely necessary, but that this isn’t the way to do it.”

Still, Powell says he was surprised by how fast the administration took action. Throughout his senior year, he worked on a thesis project that compared the agency’s objectives under Trump’s first administration with former President Joe Biden’s.

He planned on adding data from early in Trump’s second term but quickly found out that wouldn’t be possible. The portals he used to access these documents had been “completely wiped away,” he says.

“I wasn’t expecting the sort of scrubbing of [USAID initiatives] to go to that level.” Powell explains that he was able to finish his capstone project using documents he had downloaded before Trump retook office.

Now, after a semester of contemplation, Powell has decided to pivot. After spending four years in Wuhan, China, at Duke Kunshan University, where he witnessed these policy changes from afar, he’s returning to the U.S. to pursue a master’s degree in public health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Powell says he hasn’t ruled out a return someday to government work. “It’s still a field that I’m passionate about.” He sees the next few years as a detour, and a waiting game: “It’s more of delaying what my goals look like and where I want to be.”

“It felt like research funding was always going to be there”

Alyssa Johnson spent her senior year at Purdue University taking a step closer to her dreams of becoming a wildlife scientist.

She applied to three Ph.D. programs that focus on amphibian disease ecology – studying how infectious disease impacts amphibian populations and their ecosystems – a topic she’s been researching for four years.

But when it came time for interviews in January, and hearing back this spring, she says she felt like there were very few openings.

“Graduate admissions across the country have gone to a very low point, because universities and professors need to protect the people they already have,” she explains. “So they’re not really letting a lot of people in.”

A handful of colleges and universities around the country announced earlier this year that they will pause admissions in graduate programs and freeze hiring, in an effort to cut costs. That’s in response to the general uncertainty around higher education, and the rounds of cuts made in federal research funding.

Johnson, who majored in wildlife and spent her summers gaining research experience in labs and in the field, says she felt helpless watching everything unfold. “I thought I did everything right,” she says. “But everything that’s been going on has kind of changed my life plans.”

She believes her field was especially hard-hit, because it uses language around climate change, and the diversity of amphibians and their ecosystems.

Getting rejected from her alma mater, Purdue, and eventually deciding not to pursue one of the programs she’d been accepted to, Johnson says this semester has been very tough, involving long nights of tears and phone calls with friends.

Amid the turmoil, she’s now exploring a new interest: working in science communication, helping build public trust around science, and correcting misinformation about scientific research.

Johnson, who’s now on the job search, says she’s looking forward to reworking her career trajectory:

“Our generation is incredibly resilient,” she says. “We were young people through the COVID pandemic. We’re now young adults during this extremely tumultuous time in the federal government, and still, I see people continuing to push.”

A student body president is still on the job hunt

College was never on the mind of Bobby McAlpine, until his senior year in high school when he was offered a merit-based scholarship from Ohio State’s Office for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion.

“I found a home there,” says the university’s outgoing student body president. “I called some of [the staff] my campus aunties, campus uncles. That’s where I was able to go to make sure that I not only stayed in college, but I was able to stay afloat.”

The office, which opened in 1970, closed during McAlpine’s senior year, in February, in response to the Trump administration’s crackdown on DEI initiatives on college campuses. A month later, Ohio lawmakers introduced a separate bill on higher education that seeks to limit or eliminate DEI in all public university spaces at the state level.

Before the bill passed in late March, McAlpine organized a campus-wide campaign speaking out against it, and says he collected and delivered more than 400 letters to Ohio’s Governor Mike DeWine. The effort, he says, was joined by students from across the political spectrum.

“People feel that their government is making decisions in their name without actually consulting them,” he says.

As student body president, McAlpine says he was able to work with the college president to reallocate some scholarships and programs from the office of DEI to other university offices.

“On the one hand, we are an amazing school,” he says, giving a shout out to Ohio State’s recent national championship in college football. On the other hand, threats at both the national and state levels this semester have left students feeling “really scared,” he says:

“That’s one of the biggest things that I’ve heard from students as student body president.”

McAlpine says his last semester in the leadership role unexpectedly became one of the toughest. To meet the needs of the student body and to work with school administrators who feel just as lost, “it’s significantly grown the job to something that I never thought it would be.”

McAlpine says he has delayed his plans to pursue a law degree in the fall.

“I do want to be a lawyer. I do. I want to go to law school,” he explains. “But there is so much in flux right now. Why would I place myself in that extreme unknown? Rather than wait a few years to try and see just how this is going to affect everything?”

Despite the uncertainty and fear around higher education, he adds, “there is some positive in it, because it’s forcing so many students to form our opinions and form how we want our government to work in the future.”

He says his classmates are reading the news, learning how their public university is funded and being more politically active both on- and off-campus.

“Students are determined people,” he says. “And silence is not an option anymore.”

Transcript:

LIAM POWELL: (Reading) Dear William N. Powell…

AYESHA RASCOE, HOST:

Like millions of other American college students, Liam Powell is about to graduate and start his working life. As a global health major who interned at the United States Agency for International Development, he eyed a postgrad internship at the State Department. He applied and got chosen. Then came a hiring freeze.

POWELL: (Reading) The department hereby rescinds your tentative offer to participate in the student internship program.

RASCOE: Now Liam Powell is headed home from his time at Duke Kunshan University in China with a degree but no work in his field of choice. Alyssa Johnson planned to pursue a doctorate in ecology after her four years at Purdue.

ALYSSA JOHNSON: Graduate admissions across the whole entire country have gone to a very low point because universities and institutions and professors need to protect the people they already have.

RASCOE: And that’s forced her to reconsider. The past few months have up ended life for many graduating seniors. The White House has accused schools like Columbia or Harvard of bias. The administration has voided federal contracts and frozen research money. Bobby McAlpine is the outgoing student body president at Ohio State.

BOBBY MCALPINE: One of the biggest things that I’ve heard from students – students have come to me and just – they feel really scared. I just think that people think that a lot of or some of their government – people are making decisions in their name without actually consulting them.

RASCOE: Do you have some students, though, who are happy with the changes they’re seeing?

MCALPINE: There are people on all sides of the spectrum all the time. I mean, I delivered – I can’t even count – probably over about 400 letters to the governor of Ohio, asking him to veto a bill, Senate Bill 1 – 400 student letters from conservative students. It was from liberal students, from Black students, white students. That did pass, and it’s very unfortunate, but we’ll continue to move forward.

RASCOE: And what did that piece of legislation do?

MCALPINE: Yeah, Senate Bill 1 – unfortunately, it gets rid of all offices of diversity and inclusion in all public university spaces within the state of Ohio. The only and sole reason why I am at the Ohio State University is because of our Office of Diversity and Inclusion. That’s where I was able to go to make sure that I not only stayed in college, but I was able to stay afloat.

RASCOE: I would love to hear from the rest of you about how your postgraduation plans or even your immediate career goals have changed in the last few months. Alyssa?

JOHNSON: So I have been researching how contaminants affect amphibians and their disease dynamics for the past four years. So I was going to continue that work, and I had applied to three different graduate schools for three different PhD programs. And one school, I had a tentative offer, and what ended up happening as I got wait-listed. The research that I was doing – there were some concerns about the funding source because it had both climate and diversity in the title, so…

RASCOE: Yeah, it’s related to, like, diversity of the species.

JOHNSON: Yeah. This is quite a strange thing that’s going on with the National Science Foundation and, like, DOGE, the Department of Government Efficiency, is that they’re using either people who maybe don’t have a lot of expertise towards reviewing these grants and understanding, like, the scientific terms behind them, or they’re using things like AI to screen through the names of grants for words like diversity, equity, climate change. And so with that throughout the whole entire country, regardless of whether you’re qualified or not, you’re seeing, you know, either offers going out and then being rescinded or, you know, everybody being put on some kind of waitlist. And so that’s kind of what ended up happening.

RASCOE: Well, Liam, what were you thinking as you were seeing the Trump administration essentially dismantling USAID?

POWELL: There’s a feeling that’s pretty selfish of just knowing that the career field that I’ve spent so long studying for in my undergrad is just going to be in such a weird state of flux and toss-up for such a long time. I think that talking to a lot of professionals that work in the foreign aid and international development sector, there’s a really common perspective that reform is absolutely necessary but that this isn’t the way to do it and that this is a decision that objectively leads to the loss of a lot of lives in a way that a lot of the American public is very insulated from and just completely unaware of.

RASCOE: Bobby, you decided to push off law school for a year. Why did you decide to push it off?

MCALPINE: Well, honestly, being so inundated in the fight for higher education this past year has quite frankly put a chill down my spine. I do want to be a lawyer. I do. I want to go to law school. But over the last few years, but especially this last semester, there is so much in flux right now. Why would I place myself in that extreme unknown rather than wait a few years to try and see just how this is going to affect everything?

POWELL: Just from talking to other students – not even students that are American, but students that are coming to the U.S. to study – people are just so insanely worried and fearful about what’s happening with ICE, with people being interrogated at the border, that sort of thing. And I think the worst part is that there isn’t really anything that I can say as an American that would make the situation feel any sort of better because the amount of uncertainty is just so profound. And I completely understand why a lot of people are really reevaluating whether they want to study in the U.S. or not, like a lot of my international friends.

RASCOE: A lot of this work, like research, have a lot of ties to the government. They’re either government-funded or a lot of people would go into the government. Is that something that you see in your future or that you can see in your future now, doing research or going into government work for the federal government or what have you?

POWELL: It’s definitely not something for me that I’ve completely ruled out, and it’s still a field that I’m really passionate about. So I think that it’s more of a delaying of what my goals look like and where I want to be.

JOHNSON: I would love to be a public servant if academia didn’t work out for me. But I think the reality is that the shifts that are happening right now are making it incredibly difficult for that to happen. And like Liam was saying, it takes a lot of work. It takes a lot of time. It takes decades to get these institutions set up. And usually once those things go private or if they’re shut down, they don’t come back. And I wasn’t very tapped into that until recently because maybe this is ignorant of me, but I just felt like I didn’t have to. It felt like the funding was always going to be there.

MCALPINE: Honestly, Alyssa, that is exactly what so many students are feeling. Where we get our funding as a university, especially coming from a public university like I am, it never really crossed students’ minds. At the end of the day, America in general has really leaned into the free pursuit of thought and free pursuit of academic excellence. And that’s what makes people, just like Liam was saying, come from across the world just to have the opportunity to study in a place like the United States of America.

JOHNSON: I think one thing that you said, Bobby, that I’ve really been trying to, like, promote within, like, my friends and the people that I interact with is, like, you hear a lot of – I’m so overwhelmed right now, I feel so depressed, I feel so horrified by what’s going on, I just don’t know what to do, I’m just going to, like, delete Instagram, or I’m just going to delete my news apps. And I feel like one thing that, like, I’ve been trying to do and that I feel like a lot of, you know, like, young people are starting to shift towards is – this is so horrifying, and it is so scary, and it is so frustrating, and it makes me so angry, but I can’t look away.

MCALPINE: Silence is not an option anymore.

RASCOE: And Liam, did you have anything you wanted to say?

POWELL: I really think both Bobby and Alyssa have both put it together really well. I feel like a lot of the actions that are happening are sort of trying to isolate us and make us feel small, but that’s really not the case because we’re all going through such similar things. We have to work together for – I don’t know, for something better than this to happen. I just think that it’s going to take me a few years longer than I expected to sort of realize my postcollege dream, but I think that I’ll get there eventually.

RASCOE: We’ve been talking with college seniors, Bobby McAlpine, Alyssa Johnson and Liam Powell. Congratulations to all of you. I’m wishing you all the best of luck. Thank you so much for speaking with us.

POWELL: Thank you.

MCALPINE: Thank you. This has been an awesome conversation.

JOHNSON: Thank you for giving us a platform for our voices.

RASCOE: This segment was produced by Eleana Tworek and Janet Woojeong Lee.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Malinowski concedes to Mejia in Democratic House special primary in New Jersey

With the race still too close to call, former congressman Tom Malinowski conceded to challenger Analilia Mejia in a Democratic primary to replace the seat vacated by New Jersey Gov. Mikie Sherrill.

FBI release photos and video of potential suspect in Guthrie disappearance

An armed, masked subject was caught on Nancy Guthrie's front doorbell camera one the morning she disappeared.

Reporter’s notebook: A Dutch speedskater and a U.S. influencer walk into a bar …

NPR's Rachel Treisman took a pause from watching figure skaters break records to see speed skaters break records. Plus, the surreal experience of watching backflip artist Ilia Malinin.

In Beirut, Lebanon’s cats of war find peace on university campus

The American University of Beirut has long been a haven for cats abandoned in times if war or crisis, but in recent years the feline population has grown dramatically.

Judge rules 7-foot center Charles Bediako is no longer eligible to play for Alabama

Bediako was playing under a temporary restraining order that allowed the former NBA G League player to join Alabama in the middle of the season despite questions regarding his collegiate eligibility.

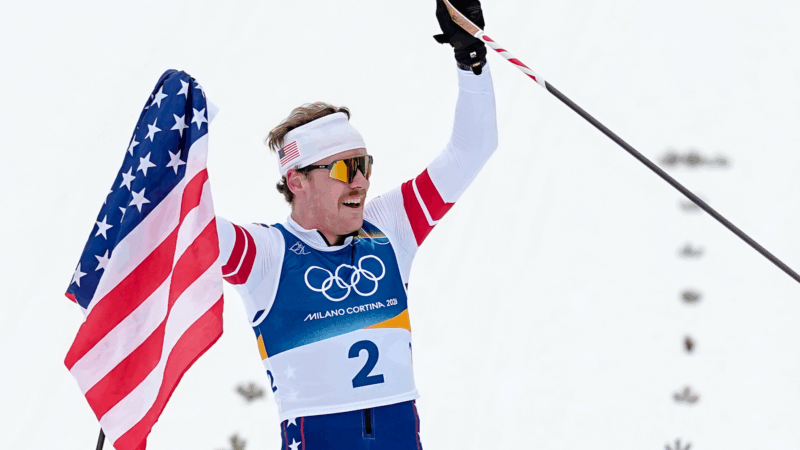

American Ben Ogden wins silver, breaking 50 year medal drought for U.S. men’s cross-country skiing

Ben Ogden of Vermont skied powerfully, finishing just behind Johannes Hoesflot Klaebo of Norway. It was the first Olympic medal for a U.S. men's cross-country skier since 1976.