Under the spell of Hildegard: A new album reboots ancient music

Barbara Hannigan is fearless in the face of new music. The Canadian soprano has sung the world premiere of over 100 new works, and last year released a recording of songs by the contemporary American composer John Zorn that even she claimed (at first) were unsingable. So it is something of a surprise that Hannigan’s new album is inspired by very old music.

Along with her musical partners — veteran pianists Katia and Marielle Labèque and electronics wiz and composer David Chalmin — Hannigan has fallen under the spell of the 12th century German abbess Hildegard von Bingen. The result, Electric Fields, is an album that unfolds like a fever dream, as if you’ve fallen asleep in a time machine.

Hildegard was a visionary poet, scientist, diplomat and composer. Her music, which continues to attract followers, is over 900 years old, but Hannigan and company view it through a singular 21st-century lens. You can hear the approach as soon as the album opens. “O virga mediatrix” (O branch and mediator) is a mesmerizing, melismatic curtain raiser, with Hannigan’s voice drenched in reverb, backed by a synthetic organ and subtle, droning electronics thanks to Chalmin’s evocative arrangement.

Hildegard may share the album with other women composers of long ago, but she looms large — even over the newly composed pieces. There are two fresh works by The National‘s Bryce Dessner in which the Labèque sisters supply lovely thickets of rippling, almost minimalist sound. But Dessner’s text for “O orzchis Ecclesia” (O measureless Church) and “O nobilissima viriditas” (O most noble greenness) is crafted from the secret language Hildegard invented for her fellow nuns.

These musicians dare to tinker with classics, unearth rare music and pull it all apart. In the song “Che t’ho fatt’io,” by 17th century composer Francesca Caccini (the first woman known to have composed an opera), Hannigan and Chalmin shuffle melodic fragments from the original tune with club beats and spiky electronic blips. It’s a dizzying haze of Baroque elegance dressed in trippy effects.

I admire Hannigan and company, working outside their comfort zones, improvising with live electronics, even in concert. Electric Fields took 10 years to realize, and even now the musicians say they’re not exactly sure what they’ve created.

Two versions of a song by Barbara Strozzi, another neglected 17th century composer, demonstrate the old-new divide on Electric Fields. One rendition of “Che si può fare” (What can be done) is presented fairly straightforwardly, although it devolves into a storm for two pianos and gurgling synths. The other version is an improvisation, nearly unrecognizable as the song amid its flurry of overdubbed voices and tolling pianos, culminating in a chaotic nightmare of electronic effects. At eight minutes long, it can sound noodling at times. Still, it effectively contributes to the larger dreamscape.

The album is both ethereal and sensual thanks to the creative arrangements and the miracle that is Hannigan’s voice. Even when obscured by audio treatments and intellectual concepts, it’s still recognizable for its signature beauty — a pure, bright, gleaming instrument, offering emotional intensity with refined phrasing and long-breathed lines.

In its incantatory final track, the album returns to Hildegard in a slowly-paced, hypnotic arrangement of “O vis aeternitatis” (O force of eternity). When they talk about seeing that great white light somewhere between life and death, this performance would make a fitting soundtrack for that unknowable journey. It ends, literally, on a high note. A 19-second-long, luscious and soaring high C, the likes of which only Hannigan can deliver.

Electric Fields is an experiment that could have gone terribly wrong. But it turned out to be a lucky meeting of disparate musicians who sparked a little dreamy magic while connecting the old with the new.

U.S. unexpectedly adds 130,000 jobs in January after a weak 2025

U.S. employers added 130,000 jobs in January as the unemployment rate dipped to 4.3% from 4.4% in December. Annual revisions show that job growth last year was far weaker than initially reported.

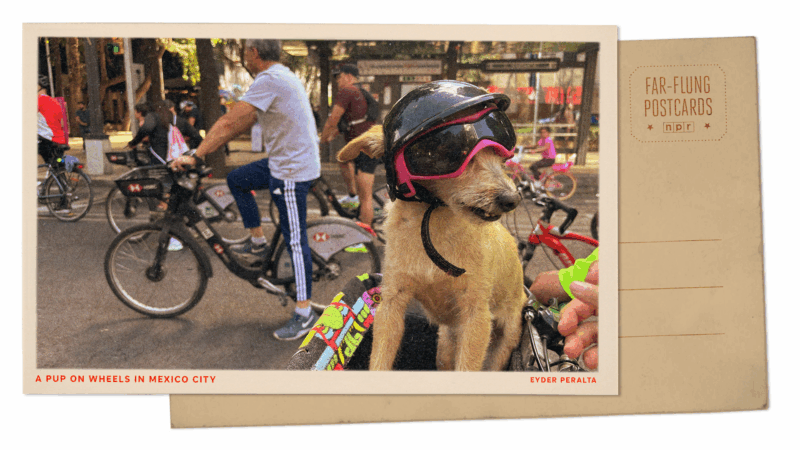

Greetings from Mexico City’s iconic boulevard, where a dog on a bike steals the show

Every week, more than 100,000 people ride bikes, skates and rollerblades past some of the best-known parts of Mexico's capital. And sometimes their dogs join them too.

February may be short on days — but it boasts a long list of new books

The shortest month of the year is packed with highly anticipated new releases, including books from Michael Pollan, Tayari Jones and the late Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa.

Shootings at school and home in British Columbia, Canada, leave 10 dead

A shooting at a school in British Columbia left seven people dead, while two more were found dead at a nearby home, authorities said. A woman who police believe to be the shooter also was killed.

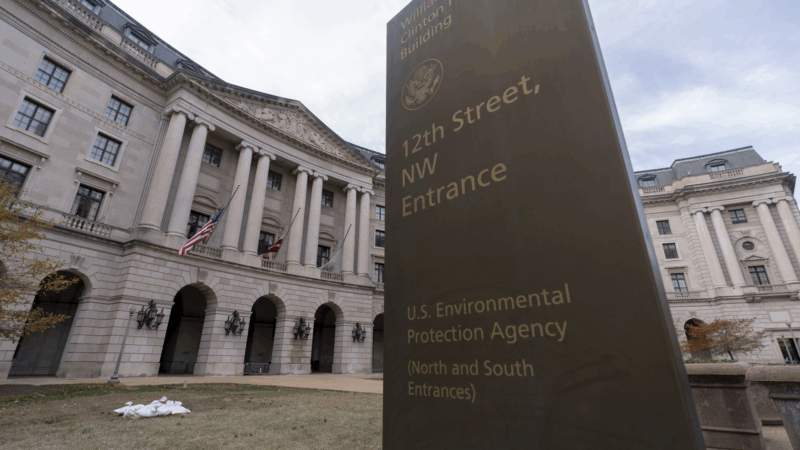

Trump’s EPA plans to end a key climate pollution regulation

The Environmental Protection Agency is eliminating a Clean Air Act finding from 2009 that is the basis for much of the federal government's actions to rein in climate change.

Pam Bondi to face questions from House lawmakers about her helm of the DOJ

The attorney general's appearance before the House Judiciary Committee comes one year into her tenure, a period marked by a striking departure from traditions and norms at the Justice Department.