To rebuild from war, Syrian firefighters work to rebuild trust — in each other

DAMASCUS, Syria — Every morning for 28 years, Haitham Nasrallah has opened his locker and put on his firefighter’s uniform. It’s a job he loves, but a uniform he now hates.

The uniform marks him as a firefighter from the old regime of dictator Bashar al-Assad, who was ousted in December 2024 after a nearly 14-year civil war.

Some of Nasrallah’s colleagues took off their uniforms and fled on the day Assad fell. But Nasrallah, 52, stayed on, hoping for a firefighting job in the new Syria. So he was still at his cement-block firehouse in the Kafr Sousa neighborhood of southwest Damascus when, three days after Assad fell, a convoy rolled in from Idlib — a northwestern Syrian city in the heart of what was once rebel territory.

“My first impression was, ‘Wow, these guys have much better equipment,'” Nasrallah recalls.

They were the White Helmets, volunteer first responders who won international fame for running into harm’s way to rescue civilians during Syria’s civil war. They’ve been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize many times. A documentary about them won a 2017 Oscar.

But for anyone who worked for the Assad regime, the White Helmets weren’t heroes. They were scary. Assad associated them with rebels attacking government forces. He and his ally Russia spread conspiracy theories about them and plastered the capital with billboards vilifying the White Helmets as traitors and terrorists.

Now, with the war over, the White Helmets’ founder Raed Saleh has been appointed to Syria’s Cabinet as minister of emergencies and disaster management. And the force he started 12 years ago is taking over firefighting duties for the entire country.

The men Nasrallah had been encouraged to think of as terrorists were suddenly moving into his barracks and becoming his bosses.

Bunking with “terrorists”

With the end of the civil war, Syrians who lived, worked — and sometimes fought — on opposite sides are coming together to rebuild their country. But as the first responders at the Kafr Sousa firehouse attest, that process requires rebuilding trust as well as state capacity. It can be sensitive, intimidating and difficult.

When NPR visited this firehouse in April, the Muslim holy month of Ramadan had recently ended and firefighters were celebrating the end-of-fasting Eid holiday. Members of the White Helmets had commandeered the kitchen for festivities.

“We’re using their kitchen. But we’re not actually eating with them,” one of the White Helmets, 33-year-old Moaz Daoud, explained as he fried eggplant. “We eat and sleep in separate quarters, because we have different morals.”

After an awkward silence, “I’m not afraid of them though,” he said. “Trust is being built.”

But a slapdash brick wall divides this firehouse: Nearly two dozen veteran firefighters live on one side, and roughly the same number of White Helmets live on the other.

When they first arrived in December, the White Helmets went room by room, looking for weapons.

“At first, they looked at us with suspicion, like we were behind Assad’s bombings and killings,” says the former regime firefighter Nasrallah, a father of four. “We have decades of firefighting experience. But they tried to sideline us. They didn’t see us as equals.”

The internationally-funded White Helmets have been earning six or seven times the former regime firefighters’ salaries. This summer, the White Helmets announced that they’re merging into Syria’s public sector. Officials say they’re not sure if or how compensation inequalities between workers from the former and current regimes will be resolved.

Nevertheless, every day, the White Helmets and former regime firefighters in the Kafr Sousa firehouse are doing the same work, responding to the same emergencies together.

They slide down fire poles from different parts of the firehouse — into the same fire trucks.

Proving loyalty

Out with a team on an emergency call, NPR asks Hussein Elyassine, another former regime firefighter, if he feels like he has to prove his loyalty to the new, post-Assad Syria. The 58-year-old simply lifts up his shirt — revealing a huge vertical scar across the length of his torso.

It’s from a shelling attack in 2014 or 2015 — he can’t recall, he says, there have been so many — which he believes the old regime ordered against its own men. He also has scars from bullet wounds to his hands and hip — from a sniper, he says, in a different incident. Four nerves in his hand were severed.

Elyassine’s house was destroyed by Assad’s forces, he says. But he’s still fighting fires daily.

Some of the White Helmets look on, see his scar, hear his stories and shake their heads, mumbling: “Respect.”

Over time, the White Helmets began inviting the former regime firefighters to work out with them. They do calisthenics in the yard, run laps around the building and pump iron in a basement gym strewn with barbells. A punching bag hangs from the ceiling.

But the process of sharing their respective past traumas and opening up with each other happens much more slowly.

“The regime threatened us not to speak about how they treated us in prison,” says Mohammed Khdeir, 30, a former regime firefighter who has braces on his teeth, slicked-back hair and sad eyes.

Khdeir says it was his lifelong dream to be a firefighter. He joined the department in 2017, after a six-month training course. A year later, he was arrested by the regime that employed him.

“Someone filed a report denouncing me as a terrorist,” he recalls. “My cousin and I both went to prison together, and he died there under torture.”

He breaks down, weeping, grabs NPR’s producer and hugs him.

Staff say 17 members of the Damascus fire department were imprisoned during Syria’s civil war, between 2011 and mid-2024. Nine of them died behind bars, according to one of the former regime firefighters, 53-year-old Nasser Bourjas.

Khdeir says he was one of the lucky ones. He was released after two and a half years.

“After I got out, I just wanted to go back to firefighting. It’s my passion, it’s my life. It’s how I want to help in the world,” he says. “But they wouldn’t let me rejoin, because I’d been in prison and had a record.”

Forming friendships across a brick wall

On the day the Assad regime fell — Dec. 8, 2024 — Khdeir rushed back to the job he loves.

“I guarded the firehouse from vandalism on that chaotic day,” he says, beaming. “I’m still not on the books. But I’ve been fighting fires like before.”

Khdeir says he’s been living and working at the Kafr Sousa firehouse ever since, without collecting a salary.

With the White Helmets now in charge of the firehouse, NPR asks them about Khdeir’s status. The White Helmets say they don’t know him — even though he’s been living in the same firehouse, on the other side of that brick wall.

“But from how you’ve described him, he sounds like a hero,” says supervisor Mustafa Bakkar, 38. “We need people like him.”

Bakkar says he’s eager to meet Khdeir. So the next day, NPR introduces the two men in the parking lot of the firehouse — and it turns out, they recognize each other. They just didn’t know each other’s names — or what the other had been through.

“I know Mohammed, I know him!” Bakkar says. “But he never told me these things.”

Sharing high-fives, hugs — and then later, inside, Eid tea and sweets — they start to share their stories: Khdeir recounts his prison experience and tells Bakkar and some of the other White Helmets about the cousin he lost, along with four other members of his extended family. Bakkar describes being wounded 10 years ago in an attack on his east Damascus neighborhood, and how he was rescued by the White Helmets — and then joined them.

“This is like group therapy!” Bakkar says.

When NPR asks when the brick wall between their barracks will be taken down, half a dozen men all chime in: “Soon, soon!”

“That wall will eventually come down,” Bakkar says. “But there’s still a psychological wall, and that one may take some time.”

Transcript:

SCOTT SIMON, HOST:

The civil war in Syria is over. Sanctions are being lifted. People who are on opposite sides are trying to come together to rebuild their country, but with difficulty. It can take time for attitudes to change, if they ever do. NPR’s Lauren Frayer found these issues at play in a Damascus firehouse.

(SOUNDBITE OF LOCKER DOOR OPENING)

HAITHAM NASRALLAH: (Speaking Arabic).

LAUREN FRAYER, BYLINE: Every morning for 28 years, Haitham Nasrallah (ph) has opened his locker and put on his uniform as a firefighter. It’s a job he loves, but a uniform he now hates.

NASRALLAH: (Speaking Arabic).

FRAYER: It marks him as a firefighter from the old regime of dictator Bashar al-Assad, who was ousted in December.

NASRALLAH: (Speaking Arabic).

FRAYER: Nasrallah recalls how some of his colleagues took off their uniforms and fled that day. But he stayed on, hoping for a firefighting job in the new Syria. And so he was still here in this cement block firehouse in southwest Damascus, when three days after Assad’s fall, a convoy rolled in from what was once rebel territory.

NASRALLAH: (Speaking Arabic).

FRAYER: Nasrallah says his first impression was just, wow. These guys had way better equipment.

(SOUNDBITE OF TELEPHONE RINGING)

NASRALLAH: (Speaking Arabic). Hello?

FRAYER: They were the White Helmets, volunteer first responders who won international fame for running into harm’s way to rescue civilians in Syria’s civil war. There was an Oscar-winning documentary about them. They operated for years on the opposite rebel side of the war, and they were demonized by the government. With the war over, the White Helmets are now taking over firefighting for all of Syria, which means the men Assad once called terrorists have suddenly moved into Nasrallah’s barracks.

(SOUNDBITE OF EGGPLANT FRYING)

FRAYER: When I visited, one of the White Helmets, Moaz Daoud (ph), was frying up eggplant for a Ramadan Iftar meal in the former regime guys’ kitchen.

So some of the firefighters here worked for the regime. And you worked against the regime. And now you’re having Iftar together. What’s…

MOAZ DAOUD: (Speaking Arabic).

FRAYER: “We’re using their kitchen,” he says. “But we’re not eating with them.” There’s actually a huge brick wall dividing their quarters. Veteran firefighters live on one side of the firehouse, and the White Helmets are on the other. When they first arrived, the White Helmets went room by room looking for weapons.

NASRALLAH: (Speaking Arabic).

FRAYER: “At first, they looked at us with suspicion,” the former regime firefighter, Nasrallah says, “like we were behind Assad’s bombings and killings.” We have decades of firefighting experience, but they tried to sideline us,” he says. “They didn’t see us as equals.”

The internationally funded White Helmets make six or seven times the firefighters’ salaries. And yet, every day, they’ve been responding to emergencies together.

(SOUNDBITE OF FIREHOUSE BELL RINGING)

JAWAD RIZKALLAH, BYLINE: Asking for – telling the people get ready and get clothed.

FRAYER: These are the fire poles, and there’s three in a row, and one is for the first floor. One’s for the second floor, and one comes all the way from the third floor. Oh, yeah, here they come.

FRAYER: Sliding down fire poles from different rooms down into the same fire trucks.

(SOUNDBITE OF FIRE TRUCK SIRENS BLARING)

FRAYER: Out on a mission, I ask another of the former regime guys, Hussein Elyassine (ph), if he, too, feels like he has to prove his loyalty to the new Syria. And instead of answering, he just lifts up his shirt.

He was shot? He was stabbed?

RIZKALLAH: No, this is from shrapnel.

FRAYER: And shows me and my producer Jawad Rizkallah a huge scar across his belly from an attack he believes the old regime ordered against its own men. Some of the White Helmets look on, shake their heads, and mumble, respect.

UNIDENTIFIED FIREFIGHTER: (Speaking Arabic).

(SOUNDBITE OF BOOTS HITTING GROUND RHYTHMICALLY)

UNIDENTIFIED FIREFIGHTER: (Speaking Arabic).

FRAYER: Over time, the White Helmets start inviting the former regime guys to work out with them…

(SOUNDBITE OF WEIGHTS CLANKING)

FRAYER: …Doing calisthenics in the yard and pumping iron in a basement strewn with barbells.

(SOUNDBITE OF WEIGHTS CLANKING)

FRAYER: But it takes us visiting and asking questions for the guys to open up with each other.

MOHAMMED KHDEIR: (Speaking Arabic).

FRAYER: “The regime threatened us not to speak about how they treated us in prison,” says 30-year-old Mohammed Khdeir (ph), who has braces on his teeth, slicked-back hair and sad eyes. It was his lifelong dream to be a firefighter. A year in, he was arrested by the regime that employed him.

KHDEIR: (Speaking Arabic).

FRAYER: “Someone denounced me,” he says, “accused me of being a terrorist.” “Me and my cousin both went to prison, and he died there under torture,” Khdeir says.

RIZKALLAH: (Speaking Arabic).

KHDEIR: (Speaking Arabic, crying).

FRAYER: He breaks down then, grabs my producer, Jawad, and hugs him.

KHDEIR: (Crying).

FRAYER: Staff here say 17 members of the Damascus Fire Department were imprisoned during the war, and nine of them died behind bars. Khdeir got out after 2 1/2 years but was banned from returning to the fire department because of his record. The day the regime fell, though, in December, he rushed back to the job he loves.

KHDEIR: (Speaking Arabic).

FRAYER: He describes guarding the fire station from vandalism that day, and he’s been living and working here ever since, without taking a salary. The day after I hear his emotional story, I mention it to the White Helmets.

Did you know that there’s a guy here who’s working for free? He still doesn’t have any salary.

One of the supervisors, a big bear of a man named Mustafa Bakkar (ph), with floppy hair and kind eyes, says…

MUSTAFA BAKKAR: (Speaking Arabic).

FRAYER: …”I don’t know who this man is that you’re talking about, who’s been through so much, but he sounds like a hero.”

(CROSSTALK)

FRAYER: They live in the same firehouse, in fact, on the same floor, on opposite sides of a single brick wall, and they’ve never met. So…

BAKKAR: (Speaking Arabic).

KHDEIR: (Speaking Arabic).

FRAYER: …We introduce them.

BAKKAR: (Speaking Arabic).

KHDEIR: (Speaking Arabic).

RIZKALLAH: He’s saying I’ve met him before. I didn’t know this was Mohammed.

FRAYER: It turns out they do know each other. They just didn’t know each other’s names or what either one had been through. Ten years ago, Bakkar had been wounded and rescued by the White Helmets and then joined them.

BAKKAR: (Speaking Arabic).

FRAYER: “This is like group therapy,” Bakkar says. “I know him. I know Mohammed, but he never told me the things he told you.”

When will they ever take down this wall between these two sides?

BAKKAR: (Speaking Arabic).

FRAYER: Soon. Soon, they promise. That brick wall in this firehouse between the old regime firefighters’ living quarters and the new ones – it will come down. “But there’s still a psychological wall,” Bakkar says, “and that may take some time.”

Lauren Frayer, NPR News in the Kafr Sousa Firehouse, Damascus.

(SOUNDBITE OF SEB WILDBLOOD’S “OF TRANSITION”)

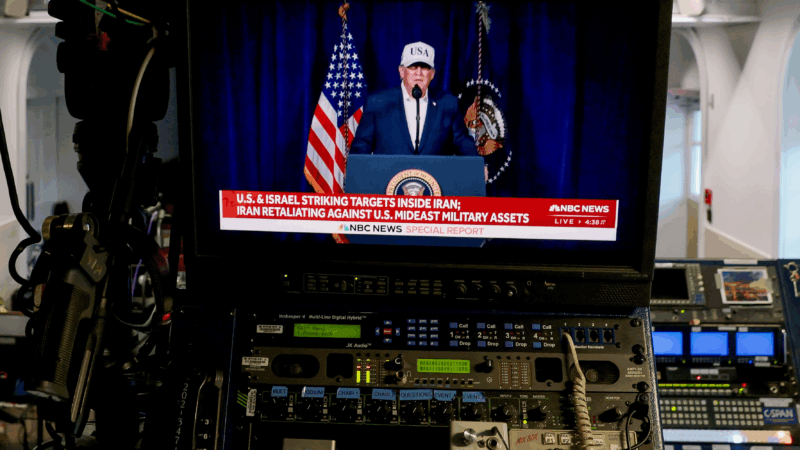

How could the U.S. strikes in Iran affect the world’s oil supply?

Despite sanctions, Iran is one of the world's major oil producers, with much of its crude exported to China.

Why is the U.S. attacking Iran? Six things to know

The U.S. and Israel launched military strikes in Iran, targeting Khamenei and the Iranian president. "Operation Epic Fury" will be "massive and ongoing," President Trump said Saturday morning.

Sen. Tim Kaine calls on the Senate to vote on the war powers resolution

NPR's Scott Simon talks to Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., about the U.S. strikes on Iran.

Iran strikes were launched without approval from Congress, deeply dividing lawmakers

Top lawmakers were notified about the operation shortly before it was launched, but the White House did not seek authorization from Congress to carry out the strikes.

Political science expert weighs in on Iran’s nuclear program in light of U.S. strikes

NPR's Scott Simon speaks to Ariane Tabatabai, the Public Service Fellow at Lawfare, about U.S. attacks on Iran and how President Trump's calls for regime change might be received there.

Week in Politics: Does Trump have political support for his actions in Iran?

We look at what President Trump's decision to attack Iran means, what kind of support he has in Iran and what this moment means for his administration.