To instill confidence, China tries to reassure private entrepreneurs of support

BEIJING — Every once in a while, China’s government makes a high-profile effort to right a wrong or rehabilitate a well-known person who has fallen from favor. They are gestures to restore public confidence in authorities.

And restoring confidence is vital for China’s economy, as it struggles to maintain slowing growth amid a mounting trade war with the U.S.

In meetings with foreign investors and domestic entrepreneurs this spring, the government has taken pains to reassure them of official support and protection, telling them they have a green light to start businesses, create jobs and benefit society. But this is a message that entrepreneurs have heard at other times over the decades, and it points to a fundamental tension between the state and private entrepreneurs.

The return of Jack Ma

One of the most telling examples was the reappearance of Jack Ma, former CEO of Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba.

In 2020, Chinese regulatory authorities launched an anti-monopoly investigation into Alibaba and suspended the massive stock market listing of Ant Group, the company’s financial arm. This happened after Ma had made comments critical of China’s financial regulators.

Ma moved to Japan, where he kept a low profile. But in February, he resurfaced at a high-profile meeting in Beijing, where China’s leader Xi Jinping hosted the nation’s top tech firm executives.

“Those who get rich first should promote common prosperity,” Xi told the CEOs.

Xi has been vague about what specific policies he will use to achieve common prosperity — a shared level of wealth or relative income equality. But the general message and context were clear.

Is the crackdown on tycoons over?

“The general background is, the private sector has been operating under tremendous regulatory pressures and constraints in the last three or four years,” says Huang Yasheng, an economist at MIT’s Sloan School of Management.

These included an antitrust investigation into a food delivery platform and penalties on a ride-hailing firm over data security.

Analysts say the aims of the crackdown on tech firms and entrepreneurs appear to include breaking up monopolies, limiting income inequality, strengthening national security, and reminding the executives who is boss.

State media neither mentioned Ma’s name nor quoted any of his remarks back in February. And yet, just the image of Ma shaking hands with Xi Jinping at the Beijing meeting was enough to signal that Ma had been rehabilitated.

It was, says Huang, “not a direct message that the crackdown was reversed, but at least the message is that from now on, you’re OK.”

Similarly, China has overturned wrongful convictions of ordinary people to try to restore public faith in China’s justice system. In one notable 2016 case, China’s Supreme Court exonerated a man more than two decades after he was executed for a murder he did not commit.

But authorities are seldom forced to admit responsibility or held accountable for these miscarriages of justice, which, to many people, “is incredibly unsatisfying” as an outcome, says Huang.

One entrepreneur wants his assets back

Besides Jack Ma, at least one other Chinese entrepreneur who fell afoul of the law hopes he’ll be rehabilitated too.

Gu Chujun was born in a rural area of eastern China 66 years ago and rose to become, according to Forbes magazine, one of China’s richest entrepreneurs around the turn of the century. He built a business empire of dozens of companies, the crown jewel of which was an appliance maker called Kelon Electrical Holdings Company.

“Local officials thought that I had run this company very well, and they wanted to take it away from me,” Gu tells NPR. “They didn’t negotiate or say, ‘I want to buy your company.’ Instead, they tried to arrest me and forced me to sell it. And if I had refused, they would have just taken it.”

Gu was arrested in 2005 and convicted of embezzlement and fraud — charges he says were trumped up. He was sentenced to 10 years in jail but served only seven.

In 2018, Xi Jinping met with business executives in a bid to reassure entrepreneurs of the government’s support and protection.

The following year, China’s Supreme Court cleared Gu of three out of four charges. But the court let stand one charge of misappropriation of funds, Gu says, so that law enforcement authorities wouldn’t be held accountable for wrongly prosecuting him.

A court awarded some $67,000 in compensation for his time in jail, but Gu says he refused the money because it was a tiny sum compared to his assets — which he wants back.

“For my company shares and 1,300 acres of land, I want $6.8 billion,” Gu says. “It’s OK if they only give me a few hundred million dollars, but not giving me a penny would be going too far.”

He is suing local governments to get his assets back, but his case is two decades old and it remains uncertain that he will succeed.

Gu notes that China’s parliament considered a new law last month that would protect private businesses from officials who try to take their money. But the law failed to pass this session of parliament.

China’s economic management agency, the National Development and Reform Commission, did not respond to questions from NPR about Gu’s case and efforts to reassure entrepreneurs.

Official reassurance in the past came during easier economic times

Huang Yasheng notes that China has previously taken high-profile measures to reassure private entrepreneurs and boost the economy, such as amending the constitution to legalize private businesses in 1988 and protect private property rights in 2004.

As of the end of 2024, China had more than 55 million private enterprises. The private sector contributed more than half of the country’s tax revenue, 60% of national gross domestic product and 80% of urban jobs, according to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology.

Huang says that encouraging the private sector was easier in the past, when “China had this pent-up entrepreneurship waiting to be unleashed into the economy.” He adds: “The situation today is entirely different.”

Today, he notes, the low-hanging fruit of productivity gains and rapid economic growth have been picked. China has produced more than the world can consume, and the country is saddled with overcapacity and heavy debt.

Now, he argues, whether Chinese entrepreneurs decide to start businesses or invest is not just about government policy. It’s also about the overall economic situation and whether people think they can make money.

And that situation is far less favorable now, he says, than the last time the government tried to reassure entrepreneurs in 2018.

Transcript:

STEVE INSKEEP, HOST:

We are reporting this week from China, which is trying to accelerate its economy amid a trade war with the United States, and we are lucky to have an observer with us who has seen decades of China’s economic rise. NPR’s Anthony Kuhn first saw this country in 1982, when it was just opening up to the world economy. And, Anthony, I assume you were about – what? – 4 or 5 years old at that point.

ANTHONY KUHN, BYLINE: (Laughter) I was a college student, Steve.

INSKEEP: (Laughter) Oh, OK – college student. He lived here as China rose. He still lives nearby in Seoul, South Korea. He’s back for a visit. And he’s brought us a story that gets at the contradictions of capitalism under communism, which is my alliteration work for the day. Anthony, what’s the story?

KUHN: Well, it’s about the Chinese government’s efforts to reassure its entrepreneurs and tell them that they have a green light to invest – to start businesses, create jobs and benefit society. But this is a message that we’ve heard many times over the course of decades, and it points to a fundamental tension between the state and private entrepreneurs. So to illustrate this, let me explain about what the government is doing now and then tell you about what happened in the past.

(APPLAUSE)

KUHN: Executives of China’s top tech firms applauded as China’s leader, Xi Jinping, and other top officials entered a huge meeting room in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

PRESIDENT XI JINPING: (Speaking Mandarin).

KUHN: As the executives sat, dutifully taking notes, Xi urged them to serve the country, focus on development, abide by the law. And…

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

XI: (Speaking Mandarin).

KUHN: …”Those who get rich first should promote common prosperity,” he said, “to make new and greater contributions to advancing China’s modernization.”

(APPLAUSE)

KUHN: Xi did not tell the executives how to spread their wealth, but he reassured them of the government’s support and protection. And that signals a significant policy shift, says Huang Yasheng, professor of global economics and management at MIT’s Sloan School.

HUANG YASHENG: So I think the general background is the private sector has been operating under tremendous regulatory pressures and constraints in the last three or four years.

KUHN: The most prominent example of China’s clipping the wings of its high-flying tech CEOs was Jack Ma, co-founder of e-commerce giant Alibaba. Authorities launched an antimonopoly investigation into Alibaba in 2020 and suspended the huge stock market listing of its financial arm shortly after Ma made comments critical of China’s financial regulators. Ma moved to Japan, where he kept a low profile. Then he resurfaced at last month’s high-profile meeting in Beijing. And while state media reports did not mention Ma’s name or quote any of his remarks, Huang says that just the image of Ma shaking hands with Xi Jinping was enough to signal that Ma had been rehabilitated. It was, Huang says…

HUANG: Not a direct message that the crackdown was reversed, but at least the message is that from now on, you’re OK.

KUHN: At least one other entrepreneur who fell afoul of the law hopes he’ll be rehabilitated, too. I met him for lunch at a restaurant in downtown Beijing. Gu Chujun was born in a rural area of East China 66 years ago and rose to become, according to Forbes magazine, one of China’s richest entrepreneurs around the turn of the century. He built a business empire of dozens of companies, the crown jewel of which was an appliance maker called Kelon Electrical Holdings Company.

GU CHUJUN: (Through interpreter) Local officials thought that I had run this company very well, and they wanted to take it away from me. They didn’t negotiate or say, I want to buy your company. Instead, they tried to arrest me and forced me to sell it. And if I had refused, they would have just taken it.

KUHN: Gu was arrested in 2005 and convicted of embezzlement and fraud – charges Gu says were trumped up. He was sentenced to 10 years in jail but served only seven. In 2018, Xi Jinping met with business executives in an earlier bid to reassure entrepreneurs. And the following year…

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED JUDGE: (Speaking Mandarin).

KUHN: …China’s Supreme Court cleared Gu of three out of four charges. But they let one charge stand, Gu says, so that law enforcement authorities wouldn’t be held accountable for wrongly prosecuting him. Gu says he was awarded some compensation for his time in jail, but he refused the money because it was a tiny sum compared to his assets, which he wants back.

GU: (Through interpreter) For my company shares and 1,300 acres of land, I want $6.8 billion. It’s OK if they only give me a few hundred million dollars, but not giving me a penny would be going too far.

KUHN: China’s economic management agency, the National Development and Reform Commission, did not respond to questions from NPR for this report. Gu notes that China’s parliament considered a new law this month that would protect private businesses from officials who try to take their money.

GU: (Through interpreter) If this private enterprise promotion law is passed, I may get some money back. If not, then the law would be useless.

KUHN: As it turned out, though, the law failed to pass this session of parliament.

INSKEEP: OK, Anthony Kuhn. Given that – given everything that you told us about the history here – what are the chances that these policy changes can get more out of private industry and help China’s economy?

KUHN: Well, Professor Huang Yasheng says that China’s government is promising to protect entrepreneurs, but it doesn’t appear that it’s going to be taking any major steps to strengthen the rule of law right away. He also says that China has previously succeeded several times in encouraging private enterprise and boosting the economy. But this time, it’s going to be harder than in past, when, he says…

HUANG: China had a huge upward potential to grow. In many ways, China had this pent-up entrepreneurship waiting to be unleashed into the economy. The situation today is entirely different.

KUHN: So today, the low-hanging fruit of easy economic gains have already been picked. External demand for Chinese exports has slumped, and the country is now saddled with a lot of overcapacity and heavy debt. So, as Professor Huang points out, whether Chinese decide to go into business or invest is not just about government policy. It’s also about the overall economic situation and whether people think they can make money in it. And that situation is far less favorable now than the last time the government tried to reassure entrepreneurs, in 2018.

INSKEEP: You know, Anthony, listening to this story, another thing that occurs to me is that in China, when you build up a fortune, that may not come with any political power.

KUHN: That’s correct. The difference between the leaders and their tech CEOs is very different. Although you see them in public – there seem to be similarities – the entrepreneur Gu Chujun told me that, unlike their U.S. counterparts, Chinese entrepreneurs really have no chance of getting any political power. And so when he looks at Elon Musk, for example, running the Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, he says that would just be unthinkable in China.

INSKEEP: Anthony, thanks for the insights. Really appreciate it.

KUHN: My pleasure, Steve.

INSKEEP: That’s NPR’s Anthony Kuhn. He is with us here in Beijing, China, where we’re reporting this week.

(SOUNDBITE OF KAMASI WASHINGTON’S “TRUTH”)

US launches new retaliatory strike in Syria, killing leader tied to deadly Islamic State ambush

A third round of retaliatory strikes by the U.S. in Syria has resulted in the death of an Al-Qaeda-affiliated leader, said U.S. Central Command.

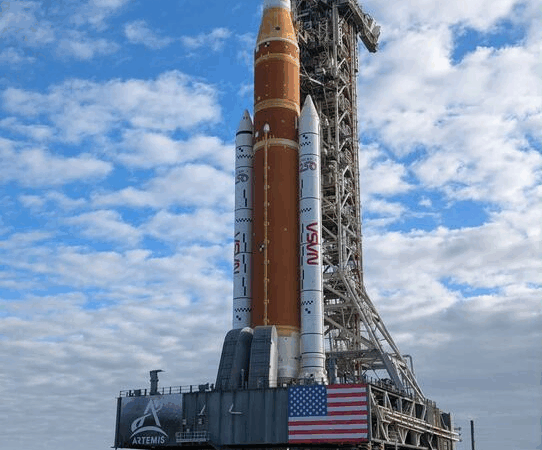

NASA rolls out Artemis II craft ahead of crewed lunar orbit

Mission Artemis plans to send Americans to the moon for the first time since the Nixon administration.

Trump says 8 EU countries to be charged 10% tariff for opposing US control of Greenland

In a post on social media, Trump said a 10% tariff will take effect on Feb. 1, and will climb to 25% on June 1 if a deal is not in place for the United States to purchase Greenland.

‘Not for sale’: massive protest in Copenhagen against Trump’s desire to acquire Greenland

Thousands of people rallied in Copenhagen to push back on President Trump's rhetoric that the U.S. should acquire Greenland.

Uganda’s longtime leader declared winner in disputed vote

Museveni claims victory in Uganda's contested election as opposition leader Bobi Wine goes into hiding amid chaos, violence and accusations of fraud.

Opinion: Remembering Ai, a remarkably intelligent chimpanzee

We remember Ai, a highly intelligent chimpanzee who lived at the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University for most of her life, except the time she escaped and walked around campus.