The Supreme Court has created an endless summer of work for itself

The Supreme Court wrapped up its term last Friday — except it didn’t.

Yes, the justices are by now heading for the beach, the golf course, or for some summer teaching gig abroad. But like it or not, they will still be working on a steady diet of emergency appeals from the Trump administration, or from immigrants being detained or deported by the administration, and much more.

That said, on the last day that the justices were in court, the conservative supermajority took unprecedented steps to strip the lower courts of the tool they have used most often to thwart Trump’s aggressive agenda on everything from the independence of government agencies and employees, to immigration and the elimination, without congressional authorization, of important government agencies.

At the same time the Supreme Court was blocking much of what the lower courts have done, the high court gave itself, and only itself, the power to block most executive orders from the president.

Indeed, Trump, for now at least, has succeeded in changing the very nature of the court’s work. The justices produced just 56 opinions this term in cases that had been briefed and argued. That’s the lowest number since the 1930’s. But in the five months since President Trump took office, the court, with only the rarest exception, has repeatedly granted his wishes to accrue power to the presidency.

A busy term on the “shadow docket”

The bulk of that work, however, has been on the so-called “shadow docket,” formally known as the “emergency docket,” which used to be primarily for last minute death penalty appeals. Today the death penalty appeals are still there, but they almost always fail, while Trump’s emergency appeals almost always win without the court having full briefing or arguments, without any signed opinion fully explaining the court’s reasoning, often without any explanation whatsoever, and almost always without any way to definitively know who voted in the majority.

“What’s striking about these cases” is that the court is almost never writing opinions that explain what it is doing, says Georgetown University law professor Stephen Vladeck. But the decisions are nonetheless “massively impactful … letting the administration continue to carry out initiatives that many think are lawless, while not necessarily settling the legality one way or the other.”

At the same time, Vladeck observes, the court is “preserving the justices’ power at some unknown future point, if they want to, to step back in and say, actually this policy, this program, this firing, was illegal.” Practically speaking, though, Vladeck says it likely will be too late to do anything about it by then.

The court, however, did step in, quite aggressively to bar the administration from deporting immigrants without giving them adequate time to challenge their deportations in court. Those orders were quite literally at the last moment before deportation, and came in the middle of the night, sending the cases back to district court judges to deal with but without explanation as to how to do that.

In other immigration cases, however, the court, again in an unsigned and brief order, allowed the administration to lift existing protections for hundreds of thousands of immigrants from Venezuela, Haiti, Cuba, Nicaragua and other countries.

With all the criticism the court is getting for its decision on nationwide injunctions, it has also gotten some support from lawyers who served in the Obama and Biden administrations because they too found almost all of the president’s executive orders barred by lower court judges, particularly in Texas.

As Notre Dame law professor Samuel Bray observes, nationwide injunctions are relatively new, really blossoming in the 21st century, and leading to overt judge-shopping, meaning that a litigant looks for a sympathetic judge and files his case there, knowing what the outcome will be. The phenomenon has been particularly evident in parts of Texas, where judges are not randomly assigned to cases, so that a litigant can be sure who the judge will be.

Some of the same issues could crop up again with the alternative paths the Supreme Court left open to stop a policy nationwide. Already class actions have been filed to challenge Trump’s birthright citizenship executive order, and the court said that states too can seek nationwide remedies for policies — such as Trump’s attempt to limit birthright citizenship.

The author of the decision barring the federal district courts from issuing nationwide injunctions was not one of the court’s more senior members. Rather Chief Justice John Roberts chose the second most junior justice to write the opinion, Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who has proven to be a disciplined writer, able to hold on to a majority. Ironically, right wing critics have assailed her for not being conservative enough, and she has faced some scary threats as a result. But this term, anyway, she proved herself to be a skilled stalwart on the conservative side of the bench.

Other notable cases

The court, of course, had lots of other consequential decisions this term in cases that were fully briefed, argued and decided. It revived a Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives regulation of unmarked and untraceable “ghost guns,” that can be put together from a kit in a matter of minutes. Until the ATF enacted the regulation, these kits could be bought online without any background check, and without presenting identification.

The conservative court also reversed nine of the 12 decisions it reviewed from the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, widely viewed as the most conservative appeals court in the country, illustrating that there are courts more conservative than the current Supreme Court. In addition to the ghost gun case, justices reversed a Fifth Circuit decision that for a third time sought to gut a major part of the Affordable Care Act.

There were also a number of big wins this term in cases involving religious rights. The conservative court majority required public schools to provide an opt out from elementary school classes when the lesson includes material that parents find contrary to their religious beliefs. And in a case involving Catholic Charities, the court said that the state of Wisconsin violated the constitution by refusing to give a Catholic social ministry organization the same exemption from paying state unemployment taxes as it gives to churches. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, the court’s senior liberal justice, wrote the opinion for a unanimous court.

The liberal justices, however, dissented when the court upheld state laws that ban gender-affirming care for minors. Roughly half the states have such laws, and the decision is likely to lead to more efforts to limit trans students in other areas, like sports.

There was no abortion case on the docket this term. But states that have a long history of opposition to abortion, won an important victory when the court, after years of resisting the question, ruled that states may deny Medicaid reimbursements to Planned Parenthood, although it is a qualified provider for a variety of non-abortion medical services.

Transcript:

ARI SHAPIRO, HOST:

It was a good year for President Trump at the Supreme Court. With decisions from executive power to deportation authority, the conservative supermajority sided with him most of the time, and in doing so, the court continued to dramatically reduce checks on the executive branch. To look back on the term that just wrapped up, NPR legal affairs correspondent Nina Totenberg is here along with Steve Vladeck of Georgetown University Law Center and Sarah Isgur of SCOTUSblog. Good to have you all here.

NINA TOTENBERG, BYLINE: We’re happy to be here.

STEVE VLADECK: Thanks for having us, Ari.

SARAH ISGUR: Yes.

SHAPIRO: What made it such a good year for President Trump? Nina, why don’t you go first?

TOTENBERG: The court essentially stripped the lower courts of some of their most important powers at the same time that it gave itself enormous power, in the vast majority of cases ruling against the lower courts, which let the administration do what it wanted. What’s more, Trump, for now at least, succeeded in changing the very nature of the court’s work because the court produced 56 opinions this term. That’s the lowest number since the 1930s. And dating myself, when I first started covering the court, they had about 140 cases a year.

SHAPIRO: Wow.

TOTENBERG: But the bulk of the work, I think, was the so-called shadow docket, what’s formerly known as the emergency docket and used to be primarily for last-minute death penalty appeals or last-minute election cases that came up. Well, guess what? The death penalty appeals are still there, but they almost always lose while the Trump emergency appeals almost always win. And there are many more of those, most of them decided without briefing and arguments and without any written opinion and without definitively knowing who voted how.

SHAPIRO: Interesting. Steve, you wrote a book about this called “The Shadow Docket.” Do you think Nina’s right that the nature of the court’s work has transformed?

VLADECK: There’s no question, Ari, and I think it’s really, really driven home this term, not just by the numbers of cases, but also by the impacts. I mean, we’ve already seen the Supreme Court have 14 different high-profile emergency applications involving Trump administration policies since April alone. I mean, that’s just in the last, you know, three months.

SHAPIRO: And this is everything from immigration to government worker layoffs to birthright citizenship and more.

VLADECK: That’s exactly right, and to President Trump’s invocation of the Alien Enemies Act. And what’s striking about all of these cases is – Nina’s right – the court is almost never writing opinions in these cases so that whether it’s granting relief to the president, which is the norm, or, in a couple of those Alien Enemies Act cases, granting relief to the detainees, you know, it’s not making a lot of law. And so it’s massively impactful from the perspective of letting the administration continue to carry out initiatives that many think are lawless, while not necessarily settling the legality one way or the other, while preserving the justices’ power at some, you know, unknown future point, if they want to, to step back in and say, actually, this policy, this program, this firing was illegal.

SHAPIRO: Sarah, this is a 6-3 court with a conservative supermajority. Three of those justices were appointed by President Trump in his first term. Did the votes consistently line up 6-3 in the major cases that you were watching?

ISGUR: No, this term, more than even the previous terms since we had those three Trump appointees join the court, felt much more like a 3-3-3 court. We had as many of the closely divided cases – so here, the 5-4s and the 6-3 – were decided with all of the liberals in dissent as were cases with all of the liberals in the majority – 15% each time.

SHAPIRO: The court did decide some major cases this term the usual way, with briefings, opinions, dissents, concurrences. Let me ask each of you for one case that you think was especially important. Steve, you want to kick us off?

VLADECK: I mean, I think, you know, the biggest case, to me, of the entire term is one that actually crosses over from the normal emergency applications procedure to oral argument. The one time the court took one of those applications and held argument, that was the birthright citizenship cases, where, you know, I think what the Supreme Court did in ruling 6 to 3, that what the, you know, Justice Barrett calls universal injunctions – that is to say, an injunction that bars the government from acting against anybody – are generally not available really, I think, does, or at least could, kneecap the ability of lower courts to block a whole slew of Trump administration initiatives, at least unless we see the very Supreme Court that was willing to narrow that kind of relief in that case, you know, all of a sudden, embrace other ways of blocking Trump policies on a nationwide basis.

SHAPIRO: Which we will quickly see because the ACLU immediately filed a class action lawsuit nationwide on behalf of people affected by the birthright citizenship executive order.

VLADECK: And that’s the tricky part, Ari, which is the most important case of the term. Just how big a deal it is actually very much remains to be seen.

SHAPIRO: Sarah, tell us about one case that jumped out to you as especially important this term.

ISGUR: So I’m going to cheat and not answer the question because, to me, it wasn’t one case, but it’s the further fracturing of the court. You know, when Chief Justice Roberts initially came into his position in 2005, he said he wanted a court like John Marshall’s, speaking with one voice. But instead, we’ve seen this proliferation of concurrences and concurring in the judgment and dissenting in part. So much so that if you look at the longest opinions of the term, of the top five, only two of them were majority opinions. The others were dissents and concurrences. So we’re really seeing, you know, what amounts to, like, nine different law firms, almost, at the court instead of…

SHAPIRO: Wow.

ISGUR: …A single court speaking with a single voice.

SHAPIRO: Are they getting along? Is there beef? Like, give us the (laughter) – what’s the soap opera story?

VLADECK: I don’t think there’s any question, Ari, that they’re not getting along, and I think part of that’s because one of the real themes of this term is that I think the stakes are higher. I mean, I realize that that’s a very strange thing to say, you know, a couple of years after Dobbs and a couple of years after Bruen. But at least from the perspective of some of the Democratic appointees, this is a term that was, and I think will continue to be all the way up to October when it formally ends, very much about whether and to what extent this court is willing to stand up to President Trump.

And I think part of what we’ve seen in the dissenting opinions from the Democratic appointees, both in some of the cases that got plenary review and in some of these emergency applications, is increasing exasperation with their colleagues in the majority not just about taking claimed procedural shortcuts and not just about, you know, avoiding anything on the merits, but about the kind of behavior and conduct by the president that these decisions are enabling – basically, a charge by the Democratic appointees that this court is not ready for this moment. even as we’re seeing lower courts, I think, do their best to stand up to President Trump, the Supreme Court keeps saying, wait, lower courts, you’ve got to slow down, without providing much of a coherent theory in exchange.

SHAPIRO: We’ve seen dissents that, and I’m paraphrasing, accuse the majority of being complicit in the erosion of American democracy…

TOTENBERG: Yeah.

SHAPIRO: …In pretty stark terms.

TOTENBERG: That’s pretty stark. And when you sit there many days a week during the argument period, what you really see is a court of people who I don’t think are – shall we put it this way? – overly fond of each other. And there’s nobody with a really great sense of humor. I mean, Scalia’s sense of humor would just sort of instantly diffuse things and you could see it. Or he would outrage people and then diffuse it. And there’s nobody like that. It’s a kind of a – you know, they’re – I have this sense that there are a bunch of people on this court who wanted these jobs and still would take them again but are not enjoying them.

SHAPIRO: That’s NPR legal affairs correspondent Nina Totenberg, Georgetown Law professor Steve Vladeck and SCOTUSblog editor Sarah Isgur. Thank you.

TOTENBERG: Thanks, Ari.

VLADECK: Thank you.

ISGUR: Thank you.

(SOUNDBITE OF THOMAS NEWMAN’S “ON THE PLUME”)

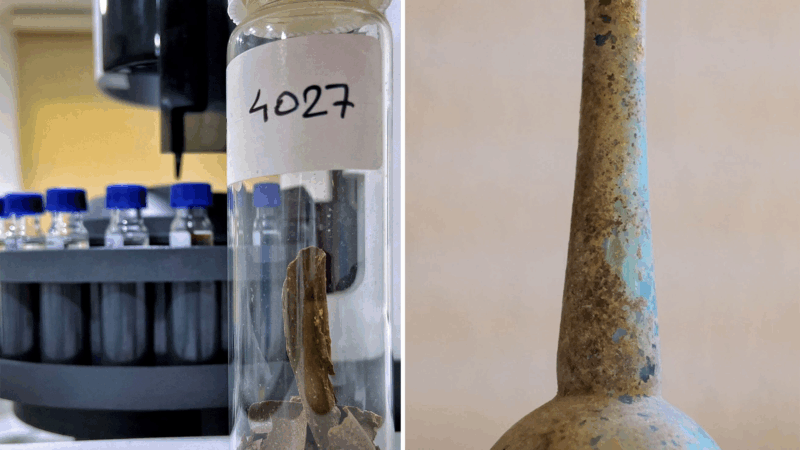

That ain’t perfume! Ancient bottle contained feces, likely used for medicine

Researchers found a tiny bottle from ancient Rome that contained fecal residue and traces of aromatics, offering evidence that poop was used medicinally more than 2,000 years ago.

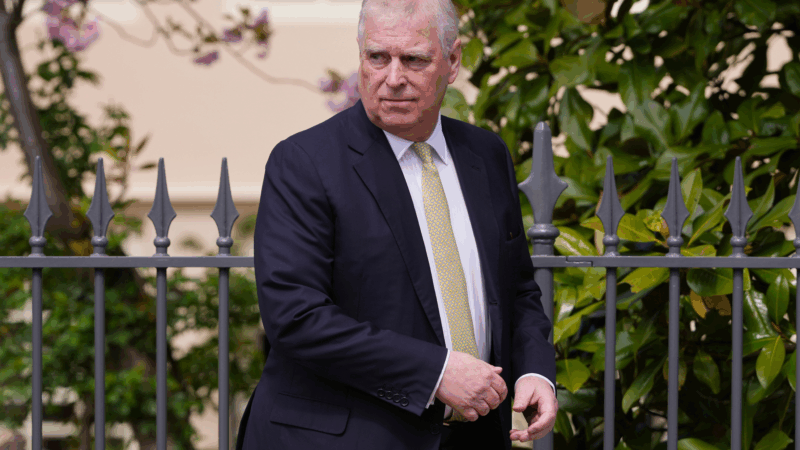

Britain’s former Prince Andrew arrested on suspicion of misconduct in public office

Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor, formerly Prince Andrew, has been arrested on suspicion of misconduct in public office.

Urban sketchers find the sublime in the city block

Sketchers say making art together in urban environments allows them to create a record of a moment and to notice a little bit more about the city they see every day.

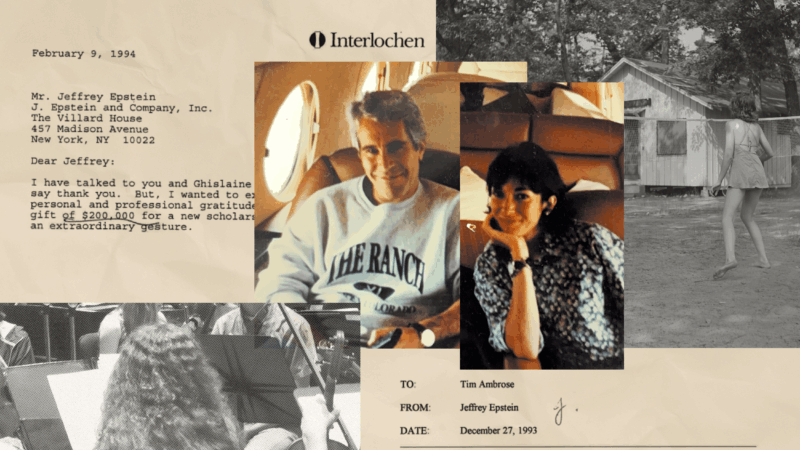

Epstein once attended an elite arts camp. Years later, he used it to find his victims

Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell lavished money on the Interlochen Center for the Arts to gain access, documents show — even funding an on-campus lodge they stayed in. In the process, two teenagers were pulled into their orbit.

An unsung hero stepped in to help a newly widowed mom in a moment of need

Barbara Alvarez lost her husband in 2017, just before their daughter went off to college. Her unsung hero helped her find the strength to be a single mother to her child at a key moment in their lives.

How a recent shift in DNA sleuthing might help investigators in the Nancy Guthrie case

DNA science has helped solve criminal cases for decades. But increasingly, investigative genetic genealogy — which was first used for cold cases — is helping to solve active cases as well.