The Panama Canal needs more water. The solution is a dam that could displace thousands

LIMÓN DE CHAGRES, Panama — Digna Benite stands on the banks of the calm Río Indio and recalls playing in the water while her father fished.

“This river is my whole life,” Benite, 60, says through a translator.

Benite’s small village, made of simple homes and one paved road, depends on this river. It sits about 10 miles west of the edge of Lake Gatún, the enormous freshwater reservoir that feeds the mighty Panama Canal. Río Indio is crucial to the canal system.

And soon, Benite and thousands of others will be forced to relocate to make way for a new dam that would drown their homes. Last week, the Panama Canal Board of Directors approved plans to build a dam to solve what it says is a long-term water shortage problem. Construction is expected to begin in 2027.

The dam project will “meet the needs for the next 50-year horizon,” says John Langman, vice president of water projects at the Panama Canal Authority.

Panama is one of the rainiest countries in the world. Many thought the country would never run out of water. But in 2023, a drought caused by El Niño got so bad that water levels and canal traffic plummeted, reducing the number of ships passing through by more than a third.

More than 50 million gallons of freshwater are required to move a vessel through a series of locks.

All Things Considered recently visited Limón de Chagres and met with a few dozen people from neighboring communities. Many of the homes we walked past had signs in Spanish saying, ‘No to the reservoir.’

‘We are happy here’

Climate researcher Steve Paton, director of the Physical Monitoring Program at the Smithsonian Institution in Panama, says scientists have not found a clear connection between El Niño and climate change.

“There is no scientific evidence as yet that these years of low rainfall” are associated with climate change, but “some strange weather patterns are emerging,” he added. “I remember in 2016, which was the previous big El Niño event, we almost ran out of water. We came really, really close. The entire city of Panama came within like a few days of running out of water.”

Then the drought in 2023 happened. At the beginning of that year, “the lake was at the lowest point it [had] ever been for that time of year and very close to a historical low level,” Paton said.

He said the driest years in more than a century of record keeping have been recorded in the last decade.

“We don’t know whether this is just an outlier, that it was just random — we just threw three double-sixes in a row — or whether it represents the canary in the coal mine where something really important has changed and we’re just at the beginning of seeing it,” Paton says.

That helps explain why Panama is looking for ways to increase the supply of freshwater.

“Right now, we are late by six years,” says Jorge Luis Quijano, a former administrator of the Panama Canal Authority, who supports the project.

The new dam would flood the basin — where people like Benite live — and produce a reservoir. The water from the reservoir would flow back into Lake Gatún and be used for the canal. In a recent news release, the Panama Canal Authority says the project would also “guarantee water supply for over 50 percent of the country’s population.”

But it will come at a cost to the people living in the area. Langman estimates that more than 2,000 people will be displaced.

“For some people who have been there for generations, it will create hardships, but we intend to be with them all along,” Langman added. “And at the end, we do expect them to be better off.”

Quijano says some of the affected communities live in areas with no electricity or potable water. The canal authority has promised a relocation package that includes “compensation, resettlement, and support for families and property owners who may be affected by the project,” according to the news release.

“We’re going to make sure that we relocate them to a place where they can continue with their life and probably improve on that,” Quijano says. “There are many things that are positive for that community, which they don’t have today.”

But people living in Limón de Chagres dispute that rationale.

Alejandrina Muñoz, another villager here, says she has everything she needs, including electricity and water.

“We are happy here. We have water, we have electricity, we have solar panels,” she says through a translator as she washes dishes with spring water that flows through her faucet.

Muñoz organized a group of people from surrounding communities who wanted to share their thoughts about being uprooted from their homes.

We asked the group whether anyone feels tempted by the life of luxury that the Panama Canal Authority promises.

A handful of people shout, “No!” They won’t accept the government’s relocation package.

“What are we going to eat in that house if we have nothing to produce ourselves?” asks 63-year-old Claudino Dominguez. He says life is about more than having a fancy house.

If anyone here supports the government proposal, we couldn’t find them.

At the end of the community gathering, villagers stood up and chanted in Spanish, “Our river is not for sale, we will defend it!”

They say their land is not for sale, but the Panama Canal Authority is still planning to move forward with the project.

Transcript:

ARI SHAPIRO, HOST:

And I’m Ari Shapiro at a small village in Panama called Limon de Chagres.

(SOUNDBITE OF RUNNING WATER)

SHAPIRO: We’re standing at the edge of this beautiful river. I can see little fish swimming just under the surface. There’s a small hand-carved wooden canoe floating under a tree. What does this body of water mean to you?

DIGNA BENITE: (Non-English language spoken).

SHAPIRO: “This river is my whole life,” says 60-year-old Digna Benite. She smiles wistfully under her straw hat. She grew up here on the Rio Indio. She would play in the water while her father caught fish.

BENITE: (Non-English language spoken).

SHAPIRO: “The water is so clean and calm,” she says, “it rises and falls. For me, it’s harmony.”

A long, narrow boat pulls up. Digna Benite and a younger man named Olegario Cedeno help us climb in, and we pull away from the shore.

(SOUNDBITE OF BOAT MOTOR STARTING)

SHAPIRO: The boat pulls over to the edge of the Rio Indio, and we climb up some steep stairs that are basically carved into the mud bank.

Olegario, what are you showing us?

OLEGARIO CEDENO: (Speaking Spanish).

SHAPIRO: “Here, I’m showing you where the dam would be,” he says.

The Rio Indio dam – it doesn’t exist yet, but authorities intend to start building it in just a couple years. Panama has been looking for solutions to a long-term problem. Every time a ship passes through the Panama Canal, more than 50 million gallons of fresh water from Lake Gatun pour out into the ocean. Nobody ever thought Panama could run out of water. It is one of the rainiest countries in the world. But a couple years ago, a drought got so bad that the canal had to reduce traffic by more than a third, which had a huge impact on global shipping. So Panama is looking for ways to get more water to the canal, and they’ve chosen this spot. A place Digna, Olegario and more than 2,000 others call home.

Digna looks out at the field where the Canal Authority plans to build the new dam. We stand in the shade of a wild coffee tree, the fragrance like honeysuckle wafting off branches full of white blossoms.

Senora Digna, when you see this place and you think about what might happen here, what goes through your head?

BENITE: (Through interpreter) I feel as if they would kill us because we wouldn’t be surrounded by nature anymore. For example, this coffee plant that we’re standing by, you know, I grab the bean. I take it. I toast it, and then that’s the coffee that I have in the mornings.

SHAPIRO: It would be simplistic to say this problem is all because of climate change. Climate scientists say the data point to a more complicated reality.

(SOUNDBITE OF BIRDS SQUABBLING)

SHAPIRO: At the shore of another body of water, tropical birds squabble in the trees at the edge of the jungle. Lake Gatun is a freshwater reservoir created by the construction of another dam more than a century ago during the creation of the Panama Canal.

STEVEN PATON: My name is Steven Paton, and I’m in charge of the Physical Monitoring Program for the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

SHAPIRO: Paton has no view on whether the much smaller Rio Indio dam should be built or not. What he does have is research, perhaps more than any other tropical rainforest in the world.

PATON: Our data goes back to 1880, when the French first arrived to start doing their construction. One of the first things they did was to install climate stations, because they knew that rainfall was going to be an incredibly important thing.

(SOUNDBITE OF FOOTSTEPS ON METAL)

SHAPIRO: We walk down a modern metal dock, a startled iguana takes a swan dive.

(SOUNDBITE OF WATER SPLASHING)

SHAPIRO: It just jumped off the dock into the water and climbed up on a rock. I can see it down there now.

Paton says, a couple years ago, that iguana might have landed on dry dirt.

PATON: Imagine – right now, the water is only about 2 feet below the level of the dock. It was something like 10, 12 feet. We had to go down a ladder to get on the boat.

SHAPIRO: And for you as a researcher, is that, like, this feels dire and frightening, or is it like, what an exciting thing to research?

PATON: Whenever you see a really impactful phenomenon, there’s the scientist side saying, wow, that’s really fascinating. But then the other human side says, ooh, that’s really bad.

SHAPIRO: The drought was caused by El Nino, and scientists have not found a clear connection between El Nino and a warming planet. But Paton says there are some strange patterns emerging. The driest years in more than a century of record-keeping, have been in just the last decade.

PATON: So we don’t know whether this is just an outlier that it was just random, we just threw three double-sixes in a row, or whether it represents the canary in the coal mine.

SHAPIRO: That helps explain why Panama is looking for ways to increase the supply of fresh water to the canal.

JORGE LUIS QUIJANO: Right now, we are late by six years.

SHAPIRO: Jorge Luis Quijano was administrator of the canal from 2012 to 2019.

QUIJANO: The funding for that project included – half of it was for actual environmental and social aspect.

SHAPIRO: What is your message to the people in the communities who would be displaced by the construction of this dam?

QUIJANO: We’re going to make sure that we relocate them to a place where they can continue with the life and probably improve on that. They are in areas where there’s no electricity. So one of the things that this project could probably provide is also hydroelectric power. They have no potable water. We would have a potable water plant as well. They have a marginal lifestyle.

(SOUNDBITE OF DISHES CLANGING)

ALEJANDRINA MUNOZ: (Through interpreter) We are happy here. We have water. We have electricity because we have solar panels. We have everything here.

SHAPIRO: Back in the village of Limon de Chagres, Alejandrina Munoz washes dishes as she prepares a breakfast of eggs, yucca and coffee sweetened with sugar cane. Everything she cooks comes from her land or from the river. She says fresh water from a nearby mountain spring flows right into her home and pours out of the tap.

If the dam is built, what will this place be?

MUNOZ: (Through interpreter) It would be underwater, and where are we going to go?

SHAPIRO: The Canal Authority told us they haven’t yet decided where displaced people would be resettled. To Munoz, this is the opposite of a marginal lifestyle. She experiences abundance more than hardship. Relatives who live in the city sometimes drive here to take extra food off her hands. There’s a hand-painted sign in front of her house.

MUNOZ: (Through interpreter) And it says, for a green Panama and for respect of the – of nature, we do not want a reservoir or a dam.

(SOUNDBITE OF ROOSTER CROWING)

SHAPIRO: As we walk through the village, most of the houses have similar signs – (speaking Spanish) – no to the reservoir, they say. Dozens of community members have gathered in a shaded outdoor meeting space next to the church to tell us how they feel. I ask the group whether anyone feels tempted by the life of luxury that the government promises.

(CROSSTALK IN SPANISH)

SHAPIRO: “No, we won’t accept it,” they say.

If anyone here supports the government proposal, we couldn’t find them. After several people express their individual views, the group stands together and joins in a chant.

UNIDENTIFIED COMMUNITY MEMBERS: (Chanting in Spanish).

SHAPIRO: “Our river is not for sale. We will defend it,” they shout.

This is almost to a word the same chant that urban Panamanians yelled as they shut down wide avenues of Panama City last week, protesting President Trump’s effort to take the Panama Canal. The villagers say this is a smaller version of the same argument. To them, it’s about sovereignty and respect.

(SOUNDBITE OF SARO TRIBASTONE’S “SERENADE”)

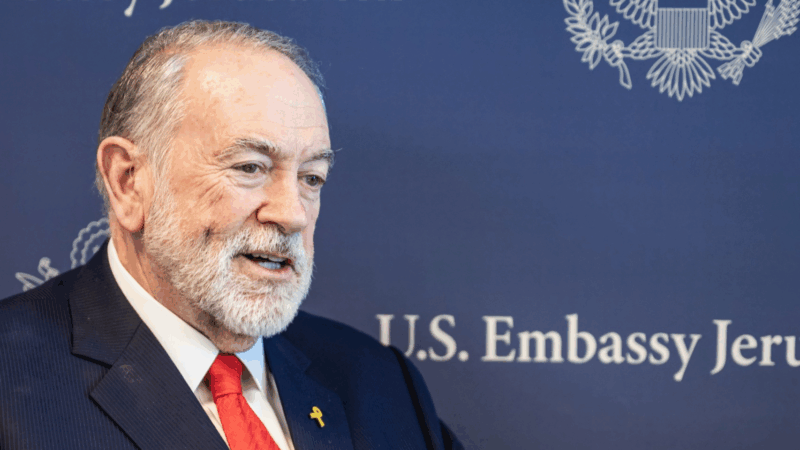

U.S. Ambassador Huckabee is ‘outraged’ at European leaders for condemning Israel

In an interview with NPR, U.S. Ambassador to Israel Mike Huckabee said the U.K., Canada and France were "blaming the wrong perpetrator," and that Hamas is responsible for the suffering in Gaza.

WBHM to welcome Report for America corps member

WBHM is excited to welcome Vahini Shori to its newsroom through a partnership with Report for America. Shori will join the station in July.

Panda Bear’s ‘Sinister Grift’ is a self-assured, midlife joyride

The Animal Collective member's eighth solo album navigates fatherhood and friendship with lots of sonic panache.

A salmonella outbreak sickens dozens, prompting a cucumber recall. Here’s what to do

The FDA says 26 people, nine of whom were hospitalized, have gotten sick across 15 states. It is still figuring out where the cucumbers were distributed — and warning people to take extra precautions.

Judge says Trump administration violated court order on third-country deportations

The Department of Homeland Security had earlier said eight people on a flight out of the U.S. had been convicted of crimes in the United States and that they couldn't be brought back.

Sleep Token is the second hard-rock band to hit No. 1 in 3 weeks

This week the lore-rich, genre-smashing, entirely anonymous hard-rock band Sleep Token lands its first-ever No. 1 album. Elsewhere, on the Hot 100 singles chart, Kendrick Lamar's "Luther (feat. SZA)" registers a 13th consecutive week at No. 1.