The American tailgate: Why strangers recreate their living rooms in a parking lot

PHILADELPHIA — In the hours before kickoff, the parking lots outside Lincoln Financial Field turn into a carnival. Amid a sea of green tents, Philadelphia Eagles fans in vintage jerseys toss footballs, grill up sausages and cheesesteaks, make elaborate cocktails on the beds of pickup trucks and dance to music from DJ decks.

“There’s nothing like this in the world,” marvels Kenny Justice, 59, who is a frequent caller to WIP, Philadelphia sports talk radio, and has been a Birds fan since at least first grade.

Justice is on to something. English soccer fans have their pints and pubs, but the tailgate is a uniquely American ritual.

Omelettes and cheesesteaks — for free

For last month’s NFC Championship game between the Eagles and the Washington Commanders, Justice and his son, Roman, 14, attended the tailgate of Ed Callahan, a retired naval intelligence officer, who’s been tailgating here for more than two decades. Callahan operates out of his massive green RV — the Eagle Mobile II — which is covered with images of legendary Eagles players, such as Hall of Fame defensive end Reggie White.

For breakfast, Callahan’s crew cooks up the tailgate’s signature omelettes with imported Irish Swiss cheese, American cheese and Philly cream cheese. Lunch is 30 to 40 pounds of cheesesteak. Callahan figures he feeds about 100 people. Half are friends, and the rest, friends of friends.

“We don’t charge money,” says Callahan, 78, “this is all hospitality.”

Callahan says core tailgate members contribute, but he estimates that this season, including the playoffs, he spent about $5,000 to fund the events.

The tailgate is an opportunity for Eagles fans, who are known for their intense devotion, to eat, drink, reminisce and blow off steam.

“I have to be professional all week,” says Justice, who owns an engineering architecture firm. “I’m a father. But then you get to come down here and you get to act like you’re a crazy kindergartener.”

What really drives this parking lot mania

It’s easy to dismiss tailgating culture, given its many excesses. But Tonya Williams Bradford, an associate professor of marketing at the University of California, Irvine, says there is something more significant and meaningful happening here.

Every fall weekend, millions of fans of professional and college football set out camping chairs and grills — effectively recreating their living rooms and kitchens — and invite in friends and strangers. She says it’s like Thanksgiving, only outdoors and open to all.

“People are investing thousands of dollars to do this over the course of a season and what they get out of it is community,” says Bradford, co-author of Domesticating Public Space through Ritual: Tailgating as Vestaval. “We’re living in an age where people may not know their next-door neighbor, but these teams bring folks together in ways that are not easily replicated.”

Bradford and her research partner spent four years interviewing tailgaters at a small Midwestern private university that they do not name in their study. They found that some tailgaters engage in a form of secular evangelism, which includes buying game tickets for guests in hopes they’ll join the tribe.

“We actually had a host of one tailgate tell us specifically that their goal every game was to convert a fan to their team,” Bradford recalled.

Tailgating’s roots are in horse-drawn coaches and sandwiches

Historians say tailgating in America began in the 19th century. Reporting on the Princeton-Yale game in 1891, the New York Tribune describes a procession of horse-drawn coaches heading up Fifth Avenue on their way to the game.

“About all the parties in the vehicles brought their luncheons with them, and little parcels of sandwiches helped while away the minutes of waiting in the stands,” the newspaper reported.

The invention of the automobile, along with the portable cooler and grill took tailgating to an entirely new level.

In modern times, tailgating is a way to honor history and pass down tradition and lore through the generations. When Kenny Justice’s son, Roman, was still in the womb, Kenny sang him the Eagles fight song, “Fly Eagles Fly.” After Roman was born, then came the Eagles onesies, pajamas and watching games at home.

“My dad, he kind of forced it down my throat, but in a friendly way,” says Roman, who is wearing a No. 6 Eagles jersey for star wide-receiver Devonta Smith.

Kenny works seven days a week, so Roman says Eagles games are a great opportunity to bond.

One of Roman’s favorite memories came this season in a game against the Jacksonville Jaguars. Father and son watched in the stands as Saquon Barkley, the Eagles star running back, pirouetted in midair and hurdled backward over a defender for a 14-yard gain. The play is regarded as one of the most remarkable of the season.

“Everyone was screaming,” recalls Roman. “We witnessed history, one of the best plays ever in football, in my opinion.”

Flipping the bird, but “it’s all love”

If the tailgate is a place for family and friends to make memories, it’s also an opportunity for people to look past their differences and come together if only for a few hours.

“I got friends here who I’ve known for years. I have no idea who they voted for,” says Kenny Justice. “I don’t care. This tailgate, in particular, everybody’s welcome.”

That includes Commanders fans such as Kenny Alvo, who’s sporting a No. 5 burgundy Commanders jersey for quarterback Jayden Daniels, NFL offensive Rookie of the Year. Alvo says the tailgate and the game are an escape from what he calls “real-life stuff,” such as bills, family issues and wars overseas.

“I can get on my phone right now and go on X, it would make me depressed within minutes,” says Alvo, 41, who works as a teacher in Fairfax County, Va. “I come to an NFC championship game, I don’t have a care in the world over here.”

While Alvo felt at home at Callahan’s tailgate, Commanders fans elsewhere in the parking lot felt the heat from some Eagles fans — who can be pretty tough on out-of-towners.

Tony Proctor drove up to the game from Southern Maryland. He was sitting with two friends in folding chairs between huge pickup trucks, out of the sight-lines from most Eagles fans.

“Come out to Philly, it’s just a whole new breed out here,” said Proctor. “They give me the finger. They curse me out real good.”

But Proctor says that’s part of the experience.

“It’s all good,” he said. “It’s all love.”

By afternoon’s end, the Eagles had beaten the Commanders, 55-23, earning them a spot in this Sunday’s Super Bowl against the reigning champs, the Kansas City Chiefs.

Transcript:

JUANA SUMMERS, HOST:

When the Philadelphia Eagles take on the Kansas City Chiefs in the Super Bowl this Sunday, a third of the country may be watching. Football is one of the few things that can bring people together in this divided nation. And there is nothing like that uniquely American tradition, the tailgate. NPR’s Frank Langfitt dropped in on one for the Eagles a couple of weeks ago, ahead of the last big game between the birds and the Super Bowl.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, “HEY YA!”)

OUTKAST: (Vocalizing).

FRANK LANGFITT, BYLINE: The parking lots outside Lincoln Financial Field this recent Sunday felt like a carnival – people tossing footballs, grilling. There’s this guy pressing oranges for drinks on the back of his pickup.

JAMIE PAGLIEI: Birds all day, baby.

LANGFITT: Superfan Jamie Pagliei wears a green mohawk and face paint. He’s certain the birds will beat the Washington Commanders today.

PAGLIEI: We going to the Super Bowl. Yeah.

(SOUNDBITE OF METAL CLINKING)

LANGFITT: Of course, no Eagles tailgate would be complete without cheesesteaks.

In this case, at least 30 to 40 pounds’ worth.

ED CALLAHAN: Ed Callahan – I’m a retired naval officer. I live in Philadelphia.

LANGFITT: This is Ed’s tailgate. He’s got a huge RV. His crew serves breakfast, an omelet with Philly cream cheese and those cheesesteaks for lunch. Today, he will feed about a hundred people.

How long you been doing this, Ed?

CALLAHAN: This is our 21st season doing this here.

LANGFITT: And who’s paying for all of this? And do you charge money?

CALLAHAN: No, we don’t charge money. This is all hospitality.

LANGFITT: Meaning core tailgate members pitch in – Callahan spent about $5,000 out of his pocket this season.

How many of these people do you know?

CALLAHAN: Probably about half of them. But the rest are friends of friends.

LANGFITT: One of those friends is Kenny Justice.

KENNY JUSTICE: Well, I was born into this. I’ve been coming to – by my uncle’s and my next-door neighbor and my friends’ since I was 5 or 6. Football in Philadelphia isn’t just a game. It’s all this.

LANGFITT: Justice sees tailgating as an escape with friends and strangers filled with joy and a shared love for the Eagles.

JUSTICE: There’s nothing like this in the world. I – you know, I own a business. I have to be professional all week. Yeah, you’re dealing with your family. I’m a father. But then you get to come down here, and you get to act like you’re a crazy kindergartner. For myself, I’m 59. Ed’s, like, 104, I think.

LANGFITT: Ed is actually 78. It’s easy to dismiss tailgate culture. But here’s the part of our story where we step away from the fun for just a moment and talk to an expert about what all this really means. Tonya Williams Bradford at the University of California Irvine has studied tailgating for years. She sees it as a kind of Thanksgiving outdoors.

TONYA WILLIAMS BRADFORD: What’s really fascinating about the tailgate is that we bring the home to the outside. And why do we do that? It’s because we’re welcoming others in to our experience. And there’s no better way to do that than to set up a living room or a lounge area and a kitchen right there outside of the stadium.

LANGFITT: And Bradford says tailgating provides something many people are missing these days.

BRADFORD: People are investing thousands of dollars to do this over the course of a season, and what they get out of it is community. We’re living in an age where people may not know their next-door neighbor, but these teams bring folks together in ways that is not easily replicated.

LANGFITT: It’s also about family and tradition. Back at the tailgate, Kenny Justice introduces me to his son, Roman, who’s 14.

ROMAN: I have watched many games forever. And my dad – he kind of forced it down my throat but in, like, the friendly way.

LANGFITT: Roman says the games are an opportunity to bond with his dad.

ROMAN: My best memory is kind of recent, actually. It’s when Saquon Barkley hurdled the dude backwards.

LANGFITT: Barkley is the Eagles’ star running back. On one play, he spun around and hurdled the defender backwards, one of the year’s biggest highlights.

ROMAN: It was crazy to watch – everyone crazy. And my dad – looked at each other, like, this is awesome.

LANGFITT: Kenny Justice says the tailgate also allows people to look past their differences if only for a few hours.

JUSTICE: I got friends here who I’ve known for years. I have no idea who they voted for. I don’t care. This tailgate in particular, everybody’s welcome.

LANGFITT: As Callahan puts it, on this Sunday morning, there’s only one party – the green party.

UNIDENTIFIED GROUP: (Chanting) E-A-G-L-E-S, Eagles.

LANGFITT: Frank Langfitt, NPR News, South Philadelphia.

(SOUNDBITE OF TOO SHORT SONG, “BLOW THE WHISTLE”)

High-speed trains collide after one derails in southern Spain, killing at least 21

The crash happened in Spain's Andalusia province. Officials fear the death toll may rise.

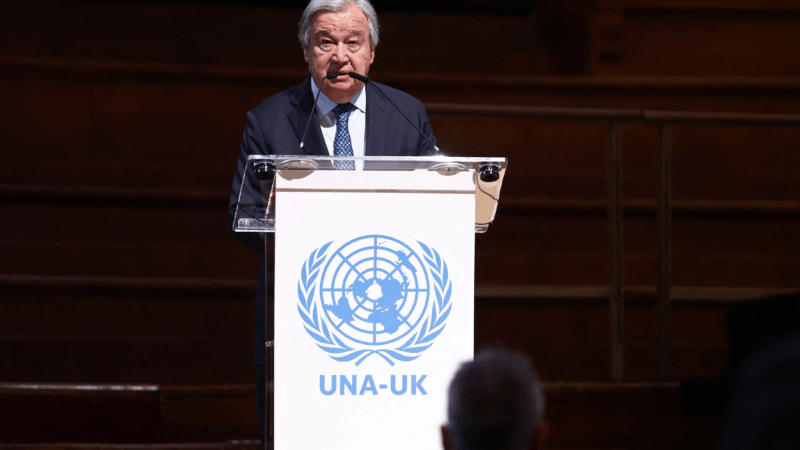

United Nations leaders bemoan global turmoil as the General Assembly turns 80

On Saturday, the UNGA celebrated its 80th birthday in London. Speakers including U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres addressed global uncertainty during the second term of President Trump.

Parts of Florida receive rare snowfall as freezing temperatures linger

Snow has fallen in Florida for the second year in a row.

European leaders warn Trump’s Greenland tariffs threaten ‘dangerous downward spiral’

In a joint statement, leaders of eight countries said they stand in "full solidarity" with Denmark and Greenland. Denmark's Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen added: "Europe will not be blackmailed."

Syrian government announces a ceasefire with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces

Syria's new leaders, since toppling Bashar Assad in December 2024, have struggled to assert their full authority over the war-torn country.

U.S. military troops on standby for possible deployment to Minnesota

The move comes after President Trump again threatened to invoke the Insurrection Act to control ongoing protests over the immigration enforcement surge in Minneapolis.