Secrets and silence haunt a grieving family in this spellbinding melodrama

Filmmaker Rungano Nyoni’s spellbinding melodrama On Becoming a Guinea Fowl begins with a woman named Shula (Susan Chardy) happening upon the dead body of her Uncle Fred on the side of an empty dirt road in Zambia one evening. Shula is eerily unmoved. She in fact appears more inconvenienced and annoyed than anything else — now she must wait with him until the authorities come, which takes hours.

This opening scene unfolds in a surreal manner, underlined by a sprinkling of magical realism and Shula’s outfit — an apparent reference to Missy Elliott’s futuristic puffy jumpsuit, bug-eyed sunglasses, and rhinestone helmet in the music video for “The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly).” Everything about it is a bit off, unmoored. But eventually, as Nyoni carefully and compassionately allows the pieces to fall into place, it makes all the sense. When it does, it resonates deeply.

Family traveling from near and far converge upon one person’s house for several days of mourning, including Shula’s grief-stricken mother (Doris Naulapwa). Most of these characters don’t stand out on their own — there are so many aunties, and with one exception, the men aren’t really the focus here — but Nyoni immerses the viewer in the complex dynamics and hierarchies at play through carefully observed interactions, right down to practices as seemingly anodyne as the preparation and serving of meals. The elders are content to let things play out as they always do, to the point of dogmatism. But an evil spirit hangs over this ritual, and it bonds Shula with her cousins Nsansa (Elizabeth Chisela) and Bupe (Esther Singini), even if they don’t recognize it at first. That spirit is in danger of being buried with Fred, instead of confronted and dealt with head-on.

Guinea Fowl‘s themes are familiar but potent, and always bear repeating when rendered as clearly and evocatively as they are here: Dark secrets regarding abuse and trauma are kept to preserve “norms” and “unity,” often at the expense of victims who suffer in silence. Older generations set the template, and each subsequent generation must decide whether to follow that example or reject it.

It’s striking to watch how the cousins attempt to resist in distinct ways. As Shula, Chardy is a stirring presence who doesn’t have to say much to convey her character’s inner turmoil and resentment, which simmer beneath her stony-faced exterior while she goes through the performative motions of grief. Nsansa too is a black sheep — boisterous, constantly drunk and blunt in her disdain for the ceremony of Fred. As the pre-burial proceedings roll on, that rough persona gives way to a softer, more vulnerable side that Chisela, a fine performer, captures wonderfully. Bupe, the youngest and most impressionable, makes more drastic choices out of a sense of helplessness.

Older generations set the template, and each subsequent generation must decide whether to follow that example or reject it.

Writer/director Nyoni, who is British-Zambian, has established herself as adept at this kind of vividly odd worldbuilding. In her great feature debut I Am Not a Witch, she cheekily and tragically explored the misogynistic and conservative social constructs which have allowed for the existence of “witch camps,” where women accused of being witches are ostracized and forced to work for local chiefs. Guinea Fowl is similarly critical of and deeply curious about the reinforcement of group-think and the power of tradition within communities, as Uncle Fred’s death sets into motion a series of long-held customs of grieving.

The film echoes I Am Not a Witch in another, very direct way: Their protagonists share the same name. In the latter, Shula (Maggie Mulubwa) is an orphaned child banished to the community of elder “witches”; they give her this name because, we’re told, it means “uprooted.” In Guinea Fowl, Shula is a grown woman, but she as well as Nsansa and Bupe are also uprooted in a way, outsiders less tethered to the ritual their elders cling to. Their rebellion doesn’t come easy, nor does it necessarily come out strong. But that’s exactly the point — the crushing weight of familial obligation and long-held social mores help explain why the cycle of obfuscation can persist.

Nyoni leaves room for hope, however, that the silence will eventually become too loud to ignore.

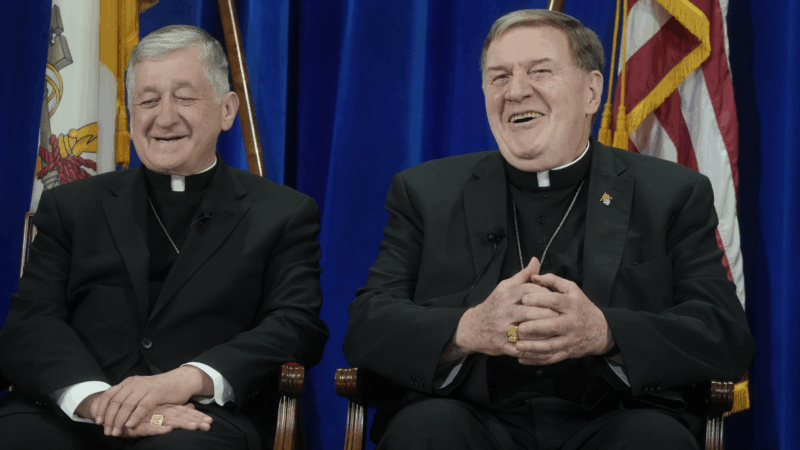

Top U.S. archbishops denounce American foreign policy

The three most-senior cardinals leading U.S. archdioceses issued the rebuke in a joint statement on Monday, saying recent policies have thrown America's "morale role in confronting evil" into question.

Italian fashion designer Valentino dies at 93

Garavani built one of the most recognizable luxury brands in the world. His clients included royalty, Hollywood stars, and first ladies.

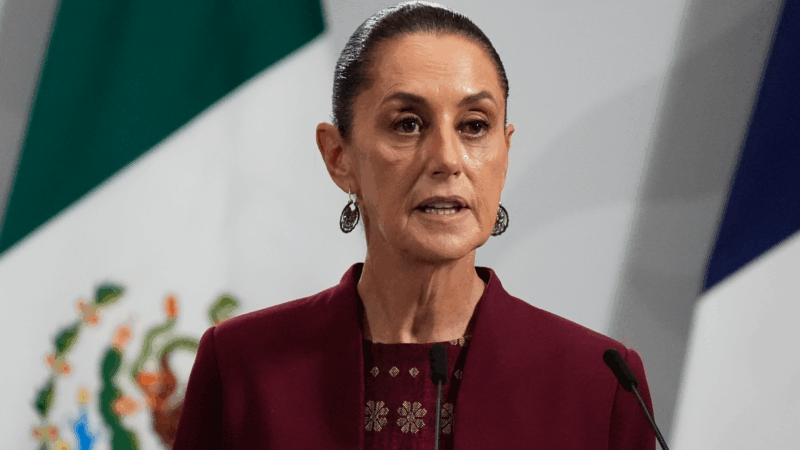

Sheinbaum reassures Mexico after US military movements spark concern

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum quelled concerns on Monday about two recent movements of the U.S. military in the vicinity of Mexico that have the country on edge since the attack on Venezuela.

Trump says he’s pursuing Greenland after perceived Nobel Peace Prize snub

"Considering your Country decided not to give me the Nobel Peace Prize… I no longer feel an obligation to think purely of Peace," Trump wrote in a message to the Norwegian Prime Minister.

Can exercise and anti-inflammatories fend off aging? A study aims to find out

New research is underway to test whether a combination of high-intensity interval training and generic medicines can slow down aging and fend off age-related diseases. Here's how it might work.

U.S. lawmakers wrap reassurance tour in Denmark as tensions around Greenland grow

A bipartisan congressional delegation traveled to Denmark to try to deescalate rising tensions. Just as they were finishing, President Trump announced new tariffs on the country until it agrees to his plan of acquiring Greenland.