Playwright Athol Fugard, who chronicled apartheid and its aftermath, dies at 92

When apartheid ended, and Nelson Mandela was elected president of South Africa, Athol Fugard thought his life as a playwright was over, he told NPR in 2015.

“I sincerely believe that I was going to be South Africa’s first literary redundancy,” Fugard said. “But as it is, South Africa caught me by surprise again and just said, ‘no, you got to keep writing, man. There are still stories to tell.’ “

And for six decades, in close to three dozen plays, Fugard told stories about the corrosive effects of a political system which oppressed the black majority in his native country, as well as stories of the white minority.

The prolific playwright died Saturday in Stellenbosch, South Africa, a town near Cape Twon. He was 92. He chronicled life both during and after apartheid in such plays as Blood Knot, Sizwe Banzi Is Dead, Sorrows and Rejoicings and “Master Harold”… and the Boys.

London theater critic Matt Wolf says Fugard wrote intimate, personal plays. “He was a miniaturist,” Wolf said. “So very many of his plays have casts of two or three. I think his broad, teeming canvas is the canvas of the imagination. He doesn’t need huge numbers of people.”

In fact, Fugard’s breakthrough 1961 play, Blood Knot featured only two actors onstage; they played brothers, one Black, the other of mixed race, who can pass for white. Fugard, who was also an actor and director, played the mixed-race brother originally.

He told NPR’s Michel Martin that the play was considered revolutionary at the time. “The play shattered one jingoistic belief that the stage belonged to things that looked like English drama,” recalled the playwright. “And the notion that a South African story would be not only possible — but would be entertaining and significant — amazed South African audiences.”

As well as audiences in London and New York. But South African authorities confiscated his passport. For much of Fugard’s career, he created in exile.

The playwright was born in 1932 and grew up in Port Elizabeth. His father was of English descent, and an alcoholic – something Fugard struggled with himself. His mother, of Afrikaans descent, was the breadwinner, running a tearoom and boarding house. Fugard said she helped him find the empathy that guided him through the years.

“Society was trying to make me conform to a set of very rigid racist ideas,” Fugard explained. “And she was endowed with just a natural sense of justice and decency. And she was asking questions about the world in which the two of us found ourselves struggling. She said to me, there must be something wrong with this.”

Fugard’s most autobiographical play, “Master Harold”… and the Boys, takes place in a tearoom, where white 17-year-old Hally spends an afternoon with two Black men who work there, Sam and Willie. They are surrogate fathers for the confused teenager, but at the play’s climax, Hally spits in Sam’s face.

Fugard told South African television in 1992: “The young Athol Fugard did in fact spit in the face of a Black man to his eternal shame. Even as I sit here now, I can remember that moment in my childhood when it happened.”

The play was banned in South Africa but was a hit around the world and filmed several times. It is a play “about a breakdown of communication, about a withdrawal away from an understanding of each other into our separate, isolated little worlds,” Fugard said.

The collision of those worlds had serious consequences during apartheid, not just for Fugard, but the Black actors he worked with. “Many of whom, because of the association with me, and it raised a very, very serious issue of conscience, ended up on Robben Island with Nelson Mandela,” Fugard said.

That notorious prison became the setting for a Tony Award-winning play, The Island, which Fugard created with actors John Kani and Winston Ntshona, based on their experiences.

“It’s interesting, just anecdotally, the number of times over the years that his name has come up and people who don’t know much about him think that he’s Black,” says critic Matt Wolf. “And when I say, ‘actually he’s white,’ they’re surprised. And I don’t think they quite realize the empathic project that his life is.”

Fugard said both his mother and the work of creating art itself forced him to be empathetic, to understand others.

“My job as an artist is to exercise and to keep my imagination strong enough to make those leaps out of my reality and into other realities,” Fugard explained. “That’s what your job is as a writer, your job is as an artist.”

It’s a job that he took seriously and the stories he told, even after apartheid, moved audiences around the world.

Former Crimson Tide quarterback AJ McCarron ends campaign for Alabama lieutenant governor

McCarron, who led the University of Alabama to back-to-back championships and played for the Cincinnati Bengals in the NFL, announced in October that he was running in the Republican primary for lieutenant governor.

More than 10% of Congress won’t return to their seats after 2026

NPR is tracking the record number of congressional lawmakers – now more than one in ten current members – who have announced plans to retire or run for a different office in 2026.

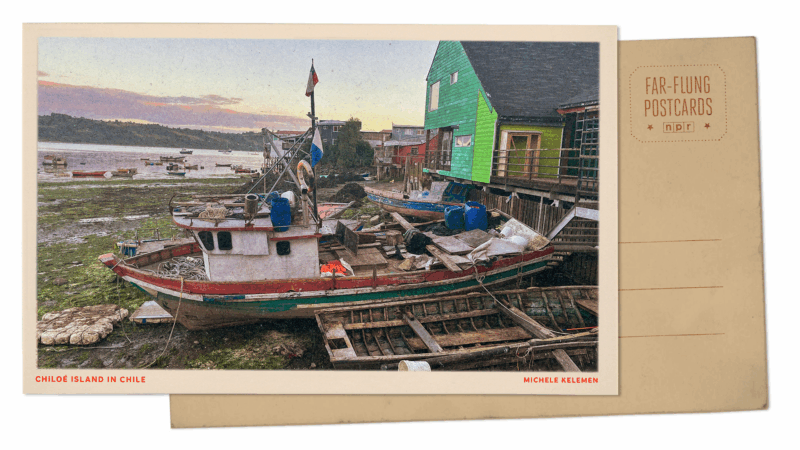

Greetings from Chiloé Island, Chile, where the fast-moving tides are part of local lore

Far-Flung Postcards is a weekly series in which NPR's international team shares moments from their lives and work around the world.

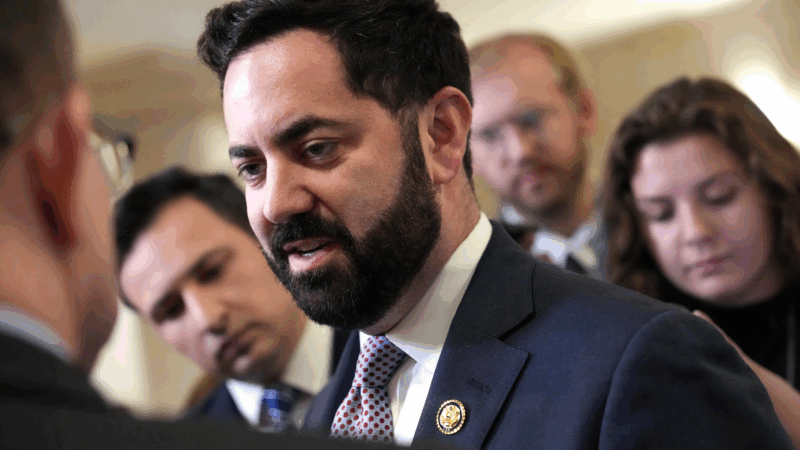

GOP House Rep. says it’s ‘unacceptable’ to allow ACA subsidies to expire

Rep. Mike Lawler says House Speaker Mike Johnson is correct in saying the health care system isn't working, but allowing ACA subsidies to expire without a plan to address rising costs is "idiotic."

Trump’s BBC lawsuit: A botched report, BritBox, and porn

President Trump's lawsuit alleges that the BBC's fall 2024 documentary was "a brazen attempt" to harm his re-election. The BBC has apologized but rejects his claim.

The best movies and TV of 2025, picked for you by NPR critics

Whether you plan to head out to the theater or binge from the couch, our critics have gathered together their favorite films and TV shows of 2025.