People told my dad not to bother educating his 4 daughters. He didn’t listen

Thank you, Dad, for standing up for your girls.

In rural Kenya, where we grew up, fathers were not expected to educate their daughters. Girls were to be married off – and not pursue an education and a career. The value of a girl was measured by her dowry, not a diploma.

jou

My father, Harrison Ngumbi, was different.

He and my mom had five children — one son and four daughters.

As he would say to us, “I choose to educate you, my girls.”

His peers would ridicule him. They’d ask why he was wasting his money on school fees for his daughters when they’ll just get married and leave.

I wanted to better understand his drive to educate us, so I called him up — he lives in Kenya and I now live 8,000 miles away in Illinois, where I’m a professor of entomology.

He says he respected girls and wanted his daughters to have a future. Perhaps he was influenced by his own mother — a single mom who worked relentlessly to raise four boys.

“It doesn’t matter what my peers think,” he told me. “My girls are my priority, and I will do everything to ensure you have an education. I want to have future professors and doctors in the family.”

“Education is the only gift I can give you,” dad would say when we were growing up. And he’s often told us:

“Work hard and be the best you can be.”

My father’s bold and reassuring words continue to play in my heart every day, inspiring me to persevere no matter what the challenge or circumstances.

Dad was an English elementary school teacher, but more than that he was visionary, a dreamer. More important, he was not afraid to defy societal norms. It was not an easy dream to follow.

He and my mother, who was also a teacher, faced a daunting reality: How to raise and educate his four daughters as well as his only son, my late brother, on a combined monthly salary of $200. Somehow, they did. But my parents had to sacrifice a lot.

I still remember how much they gave up. At the end of the month, my parents would go to the city to collect their salaries. They could have enjoyed a meal at a restaurant, eating whatever they wanted. Instead, they would return home in the evening, tired and hungry.

As a child, I could sense that they weren’t just hungry for food — there were times when it was hard to put meals on the table — but also hungry for our future.

Sometimes, my father was unable to pay full fees at the start of each the year’s three semesters, so one of the school staff would send me home and tell me I could not come back without the money.

The shame was heavy. But my father never let shame win. The next very morning, he would take me back to school. He did also bring along his pay stub to the head teacher to show that he was not withholding any money and to ask for a payment plan.

And because he gave everything, he demanded that we be fully accountable.

When we’d receive our report card at the end of each term, he wanted us to put the card on the pillow on his side of the bed. If we failed to do so, he’d punish us. And he’d punish as well if our grades weren’t good. He’d punish us until we’d cry – and then tell us not to cry.

But even more than the punishment, his silent disappointment was what hit me hardest – and made me resolve to do better.

My father’s sacrifices and his belief that girls can make it – allowed me to keep on and stay on track on my academic journey. Today, I am a professor. My sisters also have careers. Faith counsels patients who are HIV positive, Kalekye is a consultant and manager for a health-care NGO and Kavuu is a nurse. My brother, Kennedy, who died in his 40s of a lung ailment, earned his CPA and became a local businessman and a farmer.

We are women with careers, voices and choices, all because our father stood by us, and chose to educate us, believing that what men can do, women can do it better.

Thank you, Dad, for defending and standing by our right to learn, for placing our future above your comfort, for refusing to sell your daughters. Because of you, I know the meaning of sacrifice and I have vowed to fight for the next girl who is told she is not worth the cost of an education. Thank you for standing up, for us, your four girls. We are blessed to have you as our father.

Esther Ngumbi is an Assistant Professor of Entomology and African American Studies at the University of Illinois Urbana Champaign.

With a win over Sweden, the U.S. men’s hockey team will play for an Olympic medal

A thrilling overtime goal by defenseman Quinn Hughes puts Team USA through to a semifinal game against Slovakia. On the other side of the bracket, Canada had its own close call, but moves on to face Finland.

Zuckerberg grilled about Meta’s strategy to target ‘teens’ and ‘tweens’

The billionaire tech mogul's testimony was part of a landmark social media addiction trial in Los Angeles. The jury's verdict in the case could shape how some 1,600 other pending cases from families and school districts are resolved.

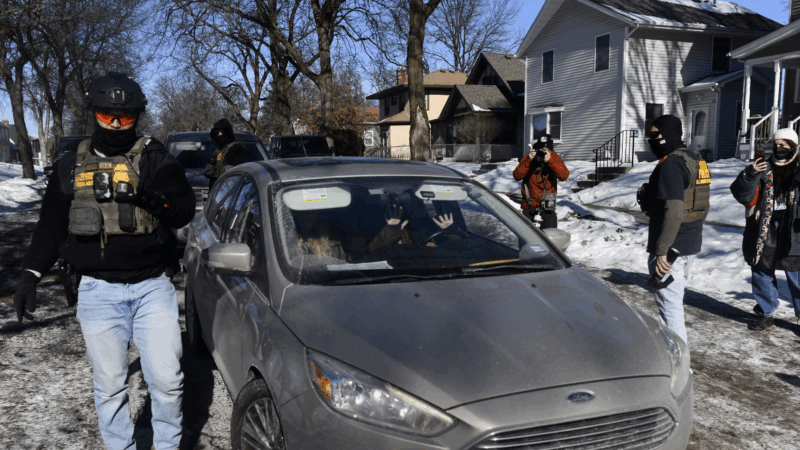

The Trump administration is increasingly trying to criminalize observing ICE

ICE officers often tell people tracking and watching them that they are breaking federal law in doing so, but legal experts say the vast majority of observers are exercising their constitutional rights.

8 backcountry skiers found dead and 1 still missing after California avalanche

Authorities say the bodies of eight backcountry skiers have been found and one remains missing after an avalanche near Lake Tahoe in California. Six others were found alive.

FDA reverses course on Moderna flu shot

The Food and Drug Administration's about-face comes a little more than a week after the agency refused to consider the company's application to market the new kind of influenza vaccine.

Following Trump’s lead, Alabama seeks to limit environmental regulations

The Alabama Legislature on Tuesday approved legislation backed by business groups that would prevent state agencies from setting restrictions on pollutants and hazardous substances exceeding those set by the federal government. In areas where no federal standard exists, the state could adopt new rules only if there is a “direct causal link” between exposure to harmful emissions and “manifest bodily harm” to humans.