One city prides itself as the cradle of the working class. Here’s why

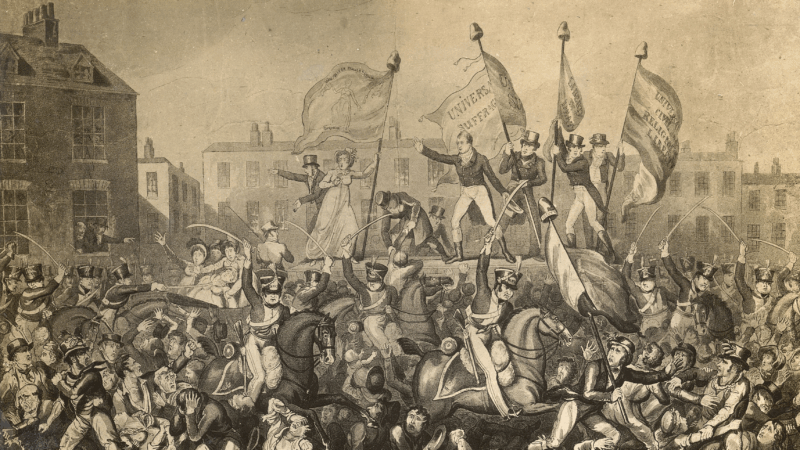

MANCHESTER, England — In the center of this industrial city in northern England, a memorial commemorates protesters killed here at a demonstration for workers’ rights in 1819, in what became known as the Peterloo Massacre. The British cavalry charged at workers who had gathered to demand political representation, killing at least 18 people and injuring hundreds.

On the monument to those killed, arrows point outward to Pennsylvania, where unarmed strikers were killed at the Lattimer mine in 1897, and to South Africa, where peaceful protesters were killed at an anti-apartheid rally in Sharpeville in 1960.

What links these places is a shared history of workers’ struggles and people’s uprisings around the world. The monument is not the only thing putting Manchester at the center of this long tradition.

Nowadays, politicians from across the political spectrum, from the United States to the United Kingdom and many countries around the world, scramble to appeal to working people, but discussions about the political power of the working class first gained prominence in 19th century Britain. This is where, during the Industrial Revolution, a new urban working class was formed and came together to demand rights and representation. Nowhere was this more evident than in Manchester.

The world’s first industrial city

Manchester was the world’s first modern industrial city, and its urban working class — and the abysmal conditions they were living in — inspired the theories of German philosophers Friedrich Engels, who lived in the city for two decades, and his friend and collaborator Karl Marx.

Engels wrote about the emergence of this group of laborers in his 1845 book, The Condition of the Working Class in England. In it, he describes “the working-men’s dwellings of Manchester” as being so terrible that “only a physically degenerate race, robbed of all humanity … could feel comfortable and at home.”

“Manchester becomes a symbol for the working classes” in the 1800s, says Charlotte Wildman, a historian at the University of Manchester.

The city’s political significance continues to reverberate around the world today.

Manchester’s rapid industrialization and the beginning of workers’ movements

In the early 19th century, Manchester became the center of the world’s cotton trade. The demand for cotton goods as part of the trans-Atlantic slave trade played a key role in the rapid industrialization of the city. Agricultural workers from across Britain moved there to work.

“There wasn’t really anywhere for them to live,” Wildman explains. “There were high levels of poverty, illness and diseases.”

At the same time, the Industrial Revolution was making some people wealthy. The huge wealth gap fueled resentment and demands for better conditions.

“That very visible sense of rich and poor gives this new urban working class a clear identity and a sense of oppression,” Wildman says.

Workers were not allowed to vote. Those in power were reluctant to give working men the vote because they didn’t trust them, she says.

“They were trying to keep away the men that they saw as undesirable, particularly the kind of men who they deemed as criminal or feckless,” she says. Women of any class weren’t even considered as deserving of the franchise.

But working-class movements began to gather pace throughout the 19th century, gradually winning over some rights for these new urban workers — although universal suffrage for men in the United Kingdom did not happen until World War I, in February 1918. The 1918 Representation of the People Act gave some women the right to vote for the first time too — but only those over 30 who owned a house or were married to a homeowner. Women did not gain universal suffrage until 1928.

Marx and Engels in Manchester

Nineteenth century thinkers flocked to Manchester to chronicle the working class, including Engels and Marx.

Engels moved to Manchester in 1842, at age 22, to manage his father’s cotton factory on the city’s outskirts. “Engels lived in Manchester for 22 years and Marx visited him there for months at a time,” says Manchester-based writer John Schofield.

Engels’ father had sent him to work at the family’s factory there “to rid him of his extreme political views,” says local historian Ed Glinert, who gives walking tours of the German philosophers’ old haunts around the city. “His father said a proper job at the family firm in Manchester would make him drop all the politics and become a good citizen.”

In fact, the city had the opposite effect on him.

“Friedrich Engels walked into a very febrile situation in Manchester in 1842,” says Schofield.

There had just been a riot of millworkers in the city and unrest and protests continued throughout the 1840s. Engels even believed they might lead to revolution in the city.

Engels and Marx would work together at a desk in the city’s Chetham’s Library, writing about workers and class struggle.

The small wooden desk in the library reading room is “one of the most important desks in the history of the world,” Schofield says. Drafts of the Communist Manifesto and Das Kapital (Capital) were written at that desk, he says, with Marx sitting at one end and Engels at the other.

Historian Wildman says the suffering the philosophers witnessed right on their doorstep helped shape their ideas.

“Marx and Engels would literally look out of the window of Chetham’s Library where they were writing and see this huge amount of poverty and people suffering,” she says.

Although Engels continued to think a revolution might happen in Manchester, in the end, it never did. But what was happening in the city was linked to and inspired other movements happening in the mid-19th century in Europe.

“There were waves of rebellions throughout Europe in the mid-19th century,” Wildman says. “People were picking up on similar processes and on the desire to have better standards of living.”

Politicians began to pay attention, too.

“What Engels and Marx did was turn the working class into a political commodity,” says local historian Glinert. “For the first time, there was a class analysis of society which people hadn’t really thought of in the past.”

The global struggle for workers’ rights, from Manchester to Pennsylvania

In Manchester’s People’s History Museum, dedicated to working-class history, the world’s oldest-surviving trade union banner hangs alongside posters linking international workers’ struggles from the 19th century to the present day.

What began in Manchester with an 1819 massacre of peasants gave birth to the world’s first workers’ movements, trade unions and an idea of equality that has fueled social justice and labor movements around the world.

The museum charts a history of international solidarity with workers that started in Manchester and that has reverberated through political discourse ever since.

Transcript:

MICHEL MARTIN, HOST:

Let’s talk more about workers overall because at least this year, American politicians have been talking a lot about them.

(SOUNDBITE OF MONTAGE)

SHAWN FAIN: Kamala Harris is fighting for working families.

DONALD TRUMP: Under my plan, American workers will no longer be worried about losing your job.

SCOTT JENNINGS: I’m interpreting the results tonight as the revenge of just the regular old working-class American.

MARTIN: Now, this phenomenon of a working class, per se, goes back to 19th century Britain. That’s when British workers during the industrial revolution united to demand rights and political power. They gave birth to a voting class that politicians all over the world still scramble to represent. NPR’s Lauren Frayer has this report from Manchester.

(SOUNDBITE OF TRAMS RUMBLING)

LAUREN FRAYER, BYLINE: We’re standing in this square. There are trams. There are glass office towers. But what happened here?

CHARLOTTE WILDMAN: So Peterloo happened in 1819. It was a protest against the lack of political representation that working people had.

FRAYER: Historian Charlotte Wildman describes how British cavalry charged protesting workers on this square that day in 1819, killing and injuring many. It became known as the Peterloo massacre. Manchester at the time was the world’s new hub of industry. But the workers themselves weren’t even allowed to vote.

WILDMAN: They have to live in awful, terrible living conditions – 10 people in one room, diseases. But the industrial revolution, those who are benefiting from that are doing very, very well financially.

FRAYER: This huge wealth gap fueled resentment, demands for better working conditions and a new sense of pride in an honest day’s work.

WILDMAN: It’s also about showing that the working poor are not feckless, drunken, that actually, they are worthy citizens, and they deserve this representation.

FRAYER: Nineteenth century thinkers flocked to Manchester to chronicle the birth of this new class or maybe what some even thought might be a revolution.

So these are the gates here through which…

(SOUNDBITE OF GATE SQUEAKING)

FRAYER: …Marx and Engels passed to go to this library.

ED GLINERT: Yeah, the library’s on the first floor there.

FRAYER: Ed Glinert gives walking tours of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ old haunts in Manchester. The German philosophers spent time here. Engels was managing his father’s factory. Marx visited him a lot. And they had a favorite desk at the city’s Chetham Library, where they wrote up their theories of class struggle, socialism and revolution. Based on what they witnessed in Manchester, Glinert says…

GLINERT: What Engels and Marx did was turn the working class into a political commodity. For the first time, there was a class analysis of society, which really people hadn’t thought of in the past.

FRAYER: And so what started with an 1819 massacre of peasants here gave birth to the world’s first trade unions and an idea of equality that has fueled social justice and labor movements around the world.

There’s a monument to the Peterloo massacre in Manchester, sort of a mosaic of tiles. I’m standing in the middle of it, and there are arrows that go out from here. One points to Sharpeville, South Africa, 1960 and the Lattimer mine in Hazleton, Pennsylvania. These are all places where there were other workers’ and people’s uprisings.

Manchester prides itself on being ground zero for working-class values, so much so that the city has a whole museum dedicated to this.

MARK WILSON: So, yeah, you just see some of the posters, placards.

FRAYER: Curator Mark Wilson showed me around the People’s History Museum of Manchester, full of old trade union banners.

Representatives from all the countries in Europe and from America…

WILSON: Yeah, yeah.

FRAYER: …Happened here.

WILSON: And you do have that sort of thread of international solidarity.

FRAYER: International solidarity with workers that started here and has reverberated through political discourse ever since.

Lauren Frayer, NPR News, Manchester.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, “WORKING CLASS HERO”)

JOHN LENNON: (Singing) A working-class hero is something to be.

Trump administration lauds plastic surgeons’ statement on trans surgery for minors

A patient who came to regret the top surgery she got as a teen won a $2 million malpractice suit. Then, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons clarified its position that surgery is not recommended for transgender minors.

Sunday Puzzle: -IUM Pandemonium

NPR's Ayesha Rascoe plays the puzzle with KPBS listener Anthony Baio and Weekend Edition Puzzlemaster Will Shortz.

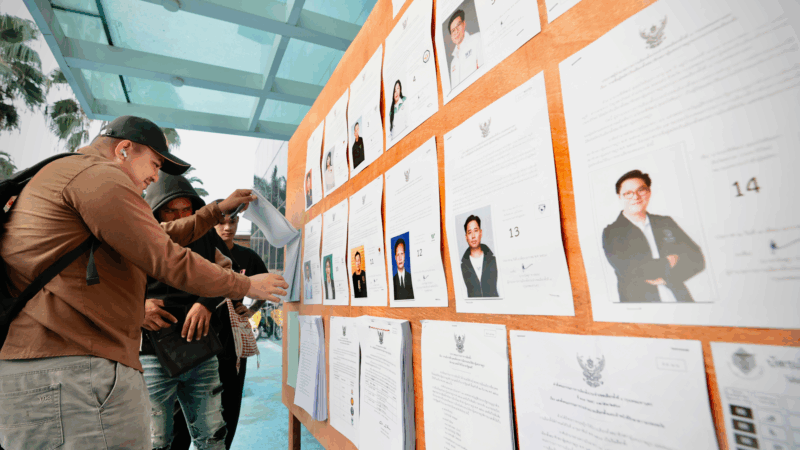

Thailand counts votes in early election with 3 main parties vying for power

Vote counting was underway in Thailand's early general election on Sunday, seen as a three-way race among competing visions of progressive, populist and old-fashioned patronage politics.

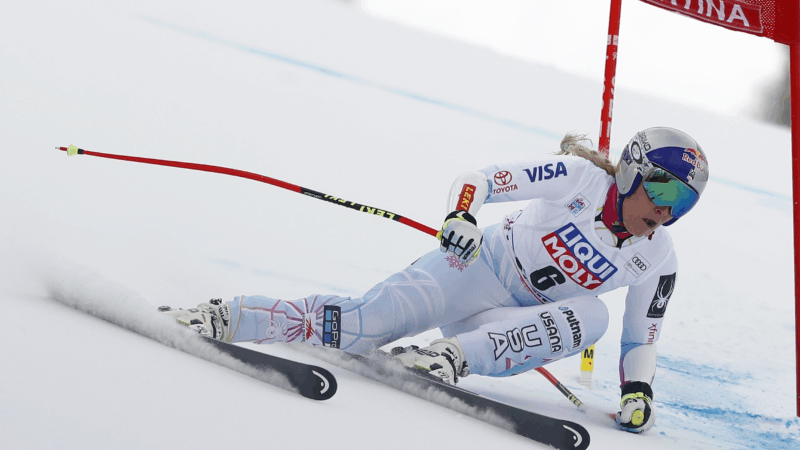

US ski star Lindsey Vonn crashes in Olympic downhill race

In an explosive crash near the top of the downhill course in Cortina, Vonn landed a jump perpendicular to the slope and tumbled to a stop shortly below.

For many U.S. Olympic athletes, Italy feels like home turf

Many spent their careers training on the mountains they'll be competing on at the Winter Games. Lindsey Vonn wanted to stage a comeback on these slopes and Jessie Diggins won her first World Cup there.

Immigrant whose skull was broken in 8 places during ICE arrest says beating was unprovoked

Alberto Castañeda Mondragón was hospitalized with eight skull fractures and five life-threatening brain hemorrhages. Officers claimed he ran into a wall, but medical staff doubted that account.