Medical research labs brace for possible funding cuts that could disrupt their work

A Trump administration plan to change how the National Institutes of Health pays for medical research at universities and other institutions has sent shock waves through labs around the country.

Dr. Donald Milton‘s lab at the University of Maryland, which studies how respiratory viruses spread, faces a threat to its funding and staffing if the new policy goes through.

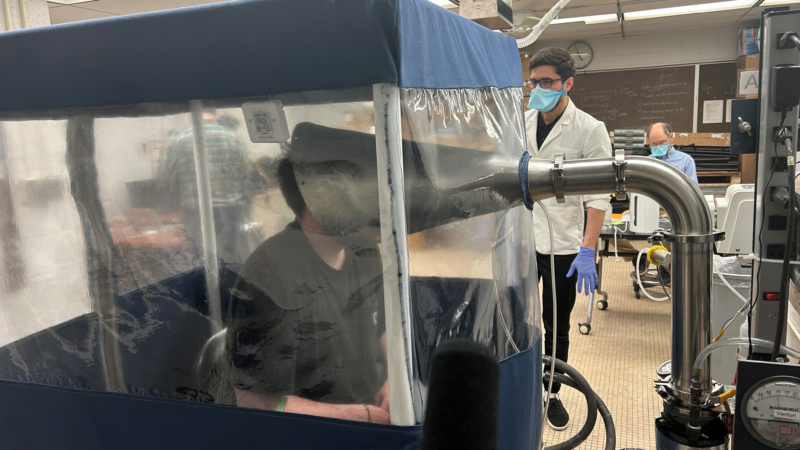

The centerpiece of his lab is a contraption inside a booth with plastic windows: A giant silver cone that resembles the horn of an old-fashioned gramophone is hooked up to a tangle of wires, tubes and cables.

This is the Gesundheit II, a research tool that collects and measures particles in people’s exhalations (or sneezes).

“We have people come in who have flu or other respiratory infections. The person sits with their face in the cone and the air around them is drawn into the cone,” says Milton, a professor of environmental health at the university’s School of Public Health in College Park, Md.

The device is one way that Milton and his colleagues study how respiratory viruses like the flu and COVID-19 spread from one person to another.

“That’s a big important question because how you stop transmission depends on how that’s happening,” he says.

But Milton says his work is threatened by the Trump administration proposal to cap indirect costs associated with medical research like his at 15%. His university has been getting about 56%.

“It would be really bad for our work,” Milton says. “It would slow us down. It may prevent us from continuing the work in the longer run.”

The NIH, which is also reeling from the layoffs of about 1,000 workers in the agency’s Bethesda, Md., campus, is the world’s largest public funder of biomedical research. The agency spends most of its $48 billion annual budget on research outside the agency, including about $9 billion in indirect costs.

“Since World War II the United States built up the world’s most effective and successful research enterprise anywhere in human history,” Milton says. “And we did that because the federal government supported the infrastructure that makes research possible. And that’s what the indirect costs do. Without that, the whole thing crumbles.”

The Trump administration says many institutions could cut bloat or use their endowments to cover those costs. That would allow the NIH to use the $4 billion in savings to pay for even more research outside the elite academic enclaves, the administration says.

Some outside experts agree.

“Rates should be reasonable for universities to cover their overhead and allow more of NIH’s budget to be directed towards actual scientific research,” says Avik Roy, president of the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity, a conservative think tank.

“The majority of people who apply for NIH funding are directed. So by directing more of the funding to scientists we can actually fund more meritorious research,” he says.

A federal judge in Boston temporarily blocked the plans to cap NIH funding of indirect costs on Feb. 10, after two lawsuits charged the change would violate federal law. U.S. District Court Judge Angel Kelley is expected to rule any day about whether the cap can go into effect. Lawyers representing the Trump administration, 22 state attorneys general and a coalition of universities, medical school, research hospitals and others presented their arguments for and against the blanket cap during a two-hour hearing on Friday.

If the plan is not stopped, Milton estimates he would lose about $1.1 million of his $3.3 million in NIH funding, forcing him to lay off up to half of his 21-member team.

“That’s what has people on edge,” Milton says. “It’s so hard to know what’s going to happen.”

The Gesundheit II is just one piece of equipment in just one of the labs that the NIH funds, where Milton and his colleagues conduct their research.

“We are having to replace pieces of our Gesundheit II because it’s now going on 20 years old and, you know, stuff wears out,” Milton says.

In fact, Milton says about one-third of what he gets from the NIH goes for indirect costs.

“The lights, the maintenance on the machinery, the heat, the air conditioning, the clerks who send out payment bills,” he says.

The funding change is just one reason staff at the NIH are on edge. They’re also nervous about the confirmation of Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a frequent critic of the agency, to run the Health and Human Services Department, which oversees the NIH. Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, another NIH critic, is President Trump’s pick to be the next NIH director.

The NIH is also trying to get the the White House to lift a freeze that’s been imposed on the agency on posting any notices in the Federal Register. That freeze is blocking the NIH from convening any new meetings, which is necessary for the agency to move forward with any new grant proposals, halting billions in research funding.

Meantime, research still goes on at Milton’s lab. A feverish student arrives to have his blood drawn, nose swabbed, saliva collected and take a turn in the Gesundheit II.

“Are you still doing all right?” one of Milton’s assistant asks the student once he’s in position. “Could I have you recite the alphabet slowly for me into the cone?”

The goal of this experiment is to help figure out how to protect people against potential threats that could cause the next pandemic, like bird flu.

“Is it airborne? Do masks work? Are there other things that we should be doing, like making sure we have good ventilation and filtration?” Milton says.

These are all questions for which scientists and the medical community would urgently like answers.

Transcript:

AYESHA RASCOE, HOST:

A federal judge in Boston is mulling a decision that could have far-reaching implications for research across the United States. The judge could rule any day on whether the Trump administration can cut billions of dollars from the overhead cost of biomedical research at universities, medical schools and hospitals. Why do overhead costs matter? NPR health correspondent Rob Stein visited one lab to find out.

ROB STEIN, BYLINE: Dr. Donald Milton’s a federally funded scientist at the University of Maryland School of Public Health. He’s among thousands of scientists around the country funded by the National Institutes of Health who are bracing for dramatic cuts in their budgets.

Can you walk me back to your lab?

DONALD MILTON: Yeah. So across the hallway here is a lab where we do our breath collections.

STEIN: Milton and his colleagues collect breath from sick people to study how respiratory viruses like the flu and COVID spread from one person to another.

(SOUNDBITE OF BEEPING)

MILTON: We do our breath collections with the Gesundheit II, which is right behind you here.

STEIN: What’s it called?

MILTON: The Gesundheit II.

STEIN: The Gesundheit II looks like a booth with clear plastic windows. Inside, there’s a giant silver cone that resembles the horn of an old-fashioned gramophone.

(SOUNDBITE OF PLASTIC RUSTLING)

STEIN: A feverish student arrives to get his blood drawn, nose swabbed, spit collected and take a turn breathing into the big metal cone.

MILTON: I’ll have him loudly recite the alphabet.

STEIN: OK.

MILTON: And meanwhile, they should be counting any coughs or sneezes that he makes.

STEIN: To try to figure out how to protect people against the next epidemic or pandemic, like the bird flu that’s infecting poultry, dairy cows and some people.

MILTON: Is it airborne? Do masks work? Are there other things that we should be doing, like making sure we have good ventilation and filtration?

STEIN: The Gesundheit II is just one piece of equipment in just one of his labs.

MILTON: We are having to replace pieces of our Gesundheit II because it’s now going on 20 years old, you know, and stuff wears out.

STEIN: In fact, Milton says about one-third of the money he gets from the NIH is for indirect costs.

MILTON: The lights, the maintenance on the machinery, the heat, the air conditioning.

STEIN: The Trump administration wants to cap indirect cost payments at 15%. The University of Maryland has been getting about 56%. So Milton estimates he would lose about $1.1 million, forcing him to lay off as many as half his team.

MILTON: It would be really bad for our work because it would slow us down. It may prevent us from continuing the work in the longer run.

STEIN: And he worries about the future of biomedical research. Most of the agency’s 48 billion annual budget goes to scientists outside the agency, like Milton, including about 9 billion for indirect costs.

MILTON: Since World War II, the United States built up the world’s most effective and successful research enterprise anywhere in human history. And we did that because the federal government supported the infrastructure that makes research possible. And that’s what the indirect costs do. And without that, the whole thing crumbles.

STEIN: Now, the Trump administration says many institutions could cut bloat or use their endowments to cover those indirect costs. And the NIH could use the $4 billion in savings to pay for even more research, especially outside the usual elite academic enclaves. Some outside experts agree. Avik Roy is president of the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity, a conservative think tank.

AVIK ROY: Rates should be reasonable for universities to cover their overhead and allow more of NIH’s budget to be directed towards actual scientific research.

STEIN: State attorneys general, medical schools, hospitals and others argued in federal court in Boston that the cap on indirect cost funding would be devastating and is illegal. The judge could rule any time.

Rob Stein, NPR News, College Park, Maryland.

U.S. issues sanctions against United Nations investigator probing abuses in Gaza

The State Department's decision to impose sanctions on Francesca Albanese, the U.N. special rapporteur for the West Bank and Gaza, follows an unsuccessful campaign to force her removal.

New data reveals FEMA missed major flood risks at Camp Mystic

The data also highlights critical risks in other areas along the Guadalupe River in Kerr County, revealing more than twice as many Americans live in flood prone areas than FEMA's maps show.

Trump sets 50% tariff rate for Brazil, blasting treatment of former far-right president

President Trump defended former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, who is accused of plotting an attempted coup following his loss in the 2022 election.

Former White House doctor declines to testify in GOP probe of Biden’s mental acuity

Kevin O'Connor cited doctor-patient confidentiality and his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination in deciding not to answer questions from Republicans on the House Oversight Committee.

Celine Song had too much fun as a matchmaker

Filmmaker Celine Song isn't religious, but that doesn't stop her from seeing certain dead insects as signs in her life and treating a good meal like prayer.

Diocese of San Bernardino issues dispensation saying Catholics who fear ICE don’t have to attend Mass

The diocese is the first in the U.S. to issue a special dispensation because of fears over immigration detentions.