Louisiana has a long history with French. This immersion school aims to keep it alive

Inside a small school down the bayou, southwest of New Orleans, two second-graders sit at a table covered with flash cards.

One card has a picture of a smiling alligator on it, along with different words for the animal: un alligator in standard French; un cocodrie in Cajun French; and then there’s caïman, a native word used by some Louisianans.

The students, Juliet Verdin and Lana LeCompte, say they like un cocodrie best because it’s fun to say: a short co-co sound and a long dree.

Juliet and Lana attend École Pointe-au-Chien, a new public French immersion school in Terrebonne Parish, La. (École means school in French, and Pointe-au-Chien, or point of the dog, is the name of the local Indian tribe and the bayou across the street.)

Louisiana has a long history with the French language, and while most Louisianans no longer speak it, a growing number of schools are immersing kids in it. At École Pointe-au-Chien, the focus is on teaching local French dialects first, an approach the school’s founders believe is unique in the state and possibly the country.

Like many of their classmates, Lana and Juliet’s ancestors spoke French — but the girls’ parents don’t. They’re the missing generation in a community where the language runs deep.

“When you lose the language, then you’re losing your culture,” says Christine Verdin, the principal of École Pointe-au-Chien (who also happens to be a distant cousin of Juliet’s).

That’s why her community started the school, she says, to close the gap and bring the language back, along with its local dialects.

The story of the French language in Louisiana

Most people used to speak French in the Pointe-au-Chien community and in Louisiana, dating back to when it was a French colony.

“The way you speak tells people about who you are,” says Nathalie Dajko, who teaches linguistics and anthropology at Tulane University.

Early French influence led to many dialects. There was the French spoken by people who came directly from France. Then, in the 1700s, more French speakers arrived from what is today Canada.

The Acadians, descendants of early French settlers in Canada, spoke something very similar, “but nonetheless distinct,” Dajko says. With time, the Acadians in Louisiana became known as the Cajuns, which is where Cajun French comes from.

And then there’s Creole, a variety of restructured French created by enslaved Africans.

Native people also learned the language and made it their own, and all those dialects mixed after the Civil War.

In the 1920s, state lawmakers tried to Americanize Louisiana by requiring that English be the only language spoken in public schools.

(Kezia Setyawan | WWNO)

The ban was in place until the 1970s. Dajko says by then, English was here to stay.

“You don’t have to punish somebody to tell them that their language is not valuable,” she says. “You just have to not use it.”

Because Native communities were initially kept out of public schools, they held onto their French longer. Dajko says the Louisianans who speak French today are often found in those communities. Their French is very close to Cajun, but with some small differences.

Louisiana’s French dialects vary in subtle ways in pronunciation and grammar, she says, and those variations are largely regional.

For example, in standard French, “what” is quoi and “who” is qui. Dajko says those words are used the same way in the southwestern part of the state, known as Cajun Country. But in the bayou parishes, southwest of New Orleans, qui is used for both.

She says the differences don’t mean French speakers from different parts of the state can’t communicate. They just have to listen to one another and problem-solve.

A language tool that can take you places

Verdin, the principal of École Pointe-au-Chien, is in her 60s and grew up speaking what she calls “Indian French” as a member of the Pointe-au-Chien Tribe.

“We all spoke French,” she says. “That’s the only way not to lose it.”

École Pointe-au-Chien is the first French immersion program in this part of the state. It’s open to any child in Terrebonne or Lafourche Parish, and it’s the result of a years-long grassroots effort to bring the French language back to the community — an effort supported by state lawmakers and Louisiana’s then-Gov. John Bel Edwards.

The school opened in fall 2023 with just nine kids and now enrolls close to 30 in pre-K through second grade. The plan is to add one grade a year until fifth or sixth grade.

Verdin says French is still a big part of the culture for the families who have stayed in this shrinking coastal community. She says at first, some tribe members wanted the kids only to learn native words. “And I had to say, ‘We can’t do that.’ “

Yes, the school is about preserving Indian and Cajun culture, she says, but French is also a tool that can take kids places. And if you don’t learn standard French, you miss part of the benefit.

“But you bring in our French, too. Because when they go home and speak to their grandparents, their grandparents are not going to know that a citrouille is a giraumon, which is a pumpkin,” Verdin says.

Bridging a generational gap

Autumn Voisin’s 7-year-old twins are in their second year at École Pointe-au-Chien.

Voisin says her grandmother was a native French speaker. “When she was mad, she was really fluent,” Voisin remembers, laughing.

Her grandmother didn’t teach her younger children or her grandchildren the language, she says, “so it died away with her.” Now, the family has a chance to reclaim their French heritage.

Watching her kids, Anna and Josiah, interact with their teachers who speak only French to them, “it’s amazing,” Voisin says. “They understand every word.”

École Pointe-au-Chien gets most of its French teachers from France through a decades-old agreement between the country and Louisiana to help preserve the language. Verdin, the school’s principal, says she had to get them up to speed on local dialects, and they’ve embraced teaching the language and all its varieties.

Sharon Picou oversees the school’s English curriculum. She says her Cajun dad was punished at school for speaking French, so he didn’t teach her and most of her siblings.

Picou understands some spoken French and wants to speak the language herself, but is sometimes too shy to try.

“It’s a confidence issue. I hope the French teachers don’t critique my French because I’m learning,” she says. “I can understand where the children are coming from when they’re a little apprehensive about speaking.”

Older kids spend more than half of the day learning in French at École Pointe-au-Chien, while pre-K students are taught entirely in French.

In Camille Revillet’s pre-K class, 4-year-olds are working on a math worksheet, counting boxes and drawing a line to the correct number.

Revillet asks a little girl, “C’est où les deux?” — Where are the twos?

“This is deux,” the girl replies, pointing to the correct number.

Dajko, the Tulane professor, says people have long predicted the demise of Louisiana French, but it keeps surviving.

For that reason, she’s not predicting anything, “but I think there’s a lot of hope these days in younger generations,” she says.

French speakers are no longer afraid to teach younger generations and more people, many of whom don’t speak French, are sending their kids to immersion schools.

People are excited about speaking French, Dajko says, and that’s what keeps a language alive.

Transcript:

SCOTT SIMON, HOST:

Louisiana has a long history with the French language, and while most Louisianans no longer speak French, a growing number of schools are immersing students in it – all kinds of it. Member station WWNO’s Aubri Juhasz takes us to a school down the bayou, southwest of New Orleans. It’s teaching students to speak some of the state’s local dialects.

JULIET VERDIN: Je m’appelle Juliet.

LANA LECOMPTE: Je m’appelle Lana.

AUBRI JUHASZ, BYLINE: Juliet Verdin and Lana LeCompte are in the second grade at a new public French immersion school, Ecole Pointe-au-Chien. Ecole means school in French. And the name of this community, Pointe-au-Chien, or point of the dog, comes from the name of the bayou across the street.

LANA: Le chat, mignon.

JUHASZ: Juliet and Lana sit at a table covered with flashcards. The cards are for words that have multiple French translations in Louisiana.

Can you tell me both ways to say alligator?

LANA: Un alligator. Un crocodi (ph).

JUHASZ: Which one do you like more?

LANA: Crocodi.

JUHASZ: That’s the Cajun word. It’s actually pronounced cocodri. And there’s another way people who speak French in this part of the state might say alligator, caiman. It’s a native word. Ecole Pointe-au-Chien focuses on local French first. Its founders believe that’s a unique approach for a French immersion school.

JULIET: (Speaking French).

JUHASZ: Juliet and Lana’s parents don’t speak French. But like most of their classmates, they have an older family member who does. Most people used to speak French in the Pointe-au-Chien community and in Louisiana, dating back to when it was a French colony. Nathalie Dajko teaches linguistics and anthropology at Tulane University.

NATHALIE DAJKO: We have the French that is spoken by these people who came directly from France.

JUHASZ: That early influence led to many dialects. In the late 1700s, more French speakers – descendants of early French settlers – arrive from what is today Canada.

DAJKO: We have a bunch of Acadians who’ve now shown up speaking something very similar but nonetheless distinct.

JUHASZ: With time, the Acadians in Louisiana became known as the Cajuns, and that’s where Cajun French comes from. There’s also Creole, which was in part created by enslaved Africans. Native people also learned the language and made it their own.

CHRISTINE VERDIN: We all spoke French. That’s the only way not to lose it.

JUHASZ: Christine Verdin is the principal of Ecole Pointe-au-Chien and is a member of the Pointe-au-Chien Indian tribe. She’s also a distant cousin of Juliet’s, the student you heard at the top. We sat down in a small office just off a classroom, where students can easily pop in, which a little boy did in the middle of our conversation.

VERDIN: What’s going on?

UNIDENTIFIED STUDENT #1: I got in a fight.

JUHASZ: Verdin, a longtime teacher, is in her 60s and grew up speaking what she calls Indian French. She describes how in the 1920s, state lawmakers tried to Americanize Louisiana by requiring English to be the only language spoken in public schools. The ban was in place until the 1970s. By then, most children had stopped speaking French at home.

VERDIN: When you lose the language which is part of your culture, then you’re losing your culture.

JUHASZ: Verdin says because Native students were initially kept out of public schools, they held onto their French longer. She learned Indian French from her parents. That put Verdin and others in her community in the position to open this school, focused on local dialects, about a year-and-a-half ago.

VERDIN: Indian French, Cajun French. We don’t have any Creoles here, but I mean, we’re not opposed.

JUHASZ: They also teach standard French, so their students – they have about 30 so far – can be part of the larger French-speaking world.

UNIDENTIFIED STUDENT #2: (Counting in French).

JUHASZ: The school’s older kids spend more than half of the day learning in French, while its youngest students are taught entirely in French. In Camille Revillet’s pre-K class, her 4-year-olds are working on a math worksheet, counting boxes and drawing a line to the correct number.

UNIDENTIFIED STUDENT #3: This is deux.

CAMILLE REVILLET: Oui.

JUHASZ: At lunch, a teacher makes small talk with the older kids in French by asking them questions about what they’re eating.

UNIDENTIFIED TEACHER: (Speaking French).

UNIDENTIFIED CHILDREN: Yeah.

JUHASZ: Dajko, the Tulan professor, says people have long predicted the demise of Louisiana French, but it keeps surviving.

DAJKO: So, I’m not going to predict anything, but I think there’s a lot of hope these days in younger generations who are choosing to speak to their children in French at home, who are sending them to French immersion schools, who are excited about speaking French.

JUHASZ: In all its many varieties.

For NPR News, I’m Aubri Juhasz, in Pointe-au-Chien, Louisiana.

(SOUNDBITE OF MITCH LANDRY AND CAJUN RAMBLERS’ “PORT ALLEN TWO-STEP”)

Pentagon is embracing Musk’s Grok AI chatbot as it draws global outcry

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth said Monday that Elon Musk's artificial intelligence chatbot Grok will join Google's generative AI engine in operating inside the Pentagon network, as part of a broader push to feed as much of the military's data as possible into the developing technology.

Offshore wind developer prevails in U.S. court as Trump calls wind farms ‘losers’

A federal judge ruled Monday that work on a major offshore wind farm can resume, handing the industry at least a temporary victory as President Trump seeks to shut it down.

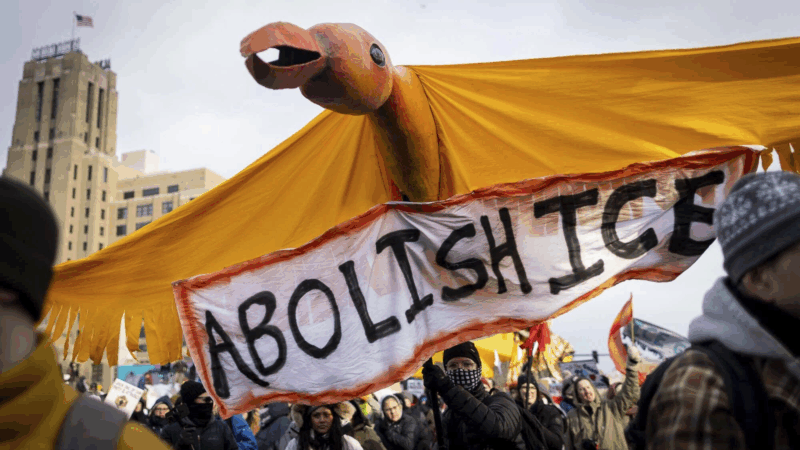

Minnesota officials sue to block Trump’s immigration crackdown as enforcement intensifies

More than 2,000 federal immigration agents are in Minnesota, and that number is expected to increase. On Monday, an NPR reporter witnessed multiple instances where immigration agents drove around Minneapolis — and in parking lots of big box stores — and randomly questioned people about their immigration status.

In photos: A week of protests against ICE

People across the country gathered to protest against ICE over the past week.

Elon Musk’s X faces bans and investigations over nonconsensual bikini images

After the social media app's AI chatbot started generating sexualized images of women and children, two countries have blocked it and several more have launched investigations.

Trump administration tells states to end ‘orphan tax’ on foster kids

There's a growing move to end what some call "the orphan tax" and stop states from taking benefit checks from children and youth in foster care.