Latest Alzheimer’s lab tests focus on memory loss, not brain plaques

When doctors suspect Alzheimer’s, they can order a blood test to learn whether a patient’s brain contains the sticky amyloid plaques that are a hallmark of the disease.

But the results of that test won’t tell the whole story, says Dr. Randall Bateman, a neurology professor at Washington University in St. Louis.

“People can have a head full of amyloid, but no dementia or memory loss,” Bateman says.

So he and a team of scientists have developed a new blood test that can show whether Alzheimer’s has actually begun to affect a person’s thinking and memory.

It joins another new test, this one of spinal fluid, that can predict whether the brain changes associated with Alzheimer’s are likely to affect cognitive function.

“It’s a strong indicator of memory impairment,” says Tony Wyss-Coray, a neurology professor at Stanford University.

Both tests, described in the journal Nature Medicine, could help doctors identify patients who are likely to benefit from drugs that can clear the brain of amyloid plaques. Both were developed with funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Looking beyond amyloid

The blood test is the result of a search for better Alzheimer’s biomarkers — measurable substances in the body that indicate the presence of a disease.

Bateman and his team had been studying tau tangles, the abnormal clumps of protein that form inside the neurons of people with Alzheimer’s. These tangles are considered a hallmark of the disease, along with amyloid plaques.

The team noticed that one region of the tau protein seemed to play a critical role in damaging neurons and causing memory loss. And they found a biomarker for this region called MTBR-tau243.

Compared with biomarkers of amyloid plaques, MTBR-tau243 “was much more related to memory loss, symptom onset, dementia stage, all the things that patients care about,” Bateman says.

At first, the team had to use spinal fluid to reliably measure levels of the new biomarker. But eventually, they developed a test that could use blood samples.

The blood test indicates how much abnormal tau is in a patient’s brain, Bateman says, “and it only goes up when people are symptomatic.”

When the test becomes available commercially, Bateman says, it will give doctors a fast and easy way to tell whether the amyloid plaques sitting in a patient’s brain are actually affecting their memory and thinking.

It will also indicate whether Alzheimer’s has progressed past the point where drug treatment is likely to help, he says.

“We can now make a much more informed choice about: How much benefit are you likely to get if you undergo a treatment to remove the amyloid plaques?” Bateman says.

A measure of synapses

Another new test, this one of spinal fluid, comes from a team led by Wyss-Coray of Stanford.

He says they set out to answer a simple question related to aging: “Can we find proteins that change if a person’s memory is not working well?”

The team studied more than 7,000 proteins in the spinal fluid of more than 3,000 people. Two proteins emerged as potential biomarkers.

Levels of one protein rose dramatically in people with memory problems, while levels of the other fell sharply.

“So we made a ratio between the two, and that ratio turns out to be a very good indicator of whether a person’s memory is OK or not,” Wyss-Coray says.

The ratio also could be used to predict eventual memory loss in people who have a genetic predisposition to Alzheimer’s.

“In these individuals, [the ratio] goes up 10 to 20 years before they get the actual disease diagnosis,” Wyss-Coray says, because that’s when the first subtle signs of cognitive impairment appear.

Both proteins in the test are involved in regulating synapses, the connections between neurons, says Dr. Paul Worley, a professor of neuroscience at Johns Hopkins University. So it makes sense that levels of these proteins change when Alzheimer’s begins to affect brain function.

“The exciting thing here is that this is a process that seems to anticipate the development of cognitive decline 10, 20, 30 years later,” Worley says. That means it should be possible to start treatment long before symptoms of Alzheimer’s start to appear, he says.

Worley was part of a team that showed how the loss of one of the two proteins used in the test disrupts synapses and leads to memory loss in Alzheimer’s. His team also found that people could remain cognitively normal despite amyloid plaques so long as their brains had normal levels of this protein.

The importance of synapses in Alzheimer’s suggests that preserving their function — perhaps by increasing levels of this protein — could be one way to treat or prevent the disease, Worley says.

“The fundamental biology supports that,” he says.

Transcript:

MARY LOUISE KELLY, HOST:

New tests of blood and spinal fluid can identify people experiencing memory loss from Alzheimer’s disease. NPR’s Jon Hamilton reports that the experimental tests could eventually help doctors diagnose the disease and could predict which patients will benefit from drug treatment.

JON HAMILTON, BYLINE: Current blood tests can show whether a person’s brain contains the sticky amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease. But Dr. Randall Bateman of Washington University in St. Louis says that’s not the whole story.

RANDALL BATEMAN: People are walking around with amyloid plaques in their brains and their brains are adapting to it and making do, but they don’t have any symptoms of it.

HAMILTON: And some never will, so Bateman and his team were excited when they found a protein fragment in spinal fluid that did indicate cognitive problems.

BATEMAN: It was much more related to memory loss, symptom onset, dementia stage – all the things that patients care about.

HAMILTON: The protein fragment, called MTBR-tau243, isn’t associated with amyloid plaques. Instead, it is closely linked to the other hallmark of Alzheimer’s – tangled fibers that build up inside neurons. And Bateman says this particular fragment rises when tangles begin affecting neurons.

BATEMAN: It only goes up when people are symptomatic. So you can look at people who are – have a headful of amyloid, and if they don’t yet have dementia, memory loss, the symptoms of Alzheimer’s, it’s still negative.

HAMILTON: Until now, the test for the protein fragment has required a spinal tap, which limited its use in clinical trials. But in a new study, Bateman’s team shows that the test works on blood samples, too. He says that means doctors should soon have an easy way to tell whether the amyloid plaques in a patient’s brain are actually affecting memory and thinking.

BATEMAN: We can now make a much more informed choice about how much benefit are you likely to get if we undergo a treatment to remove the amyloid plaques and balance that with – what is the risk?

HAMILTON: The tau243 study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, appears in the journal Nature Medicine. A second study in the same journal offers a different way to assess and even predict the memory loss associated with Alzheimer’s. Tony Wyss-Coray of Stanford University says his team set out to answer a simple question related to aging.

TONY WYSS-CORAY: Can we find proteins that change if a person’s memory is not working well?

HAMILTON: With NIH funding, the team studied more than 7,000 proteins in the spinal fluid of more than 3,000 people, and Wyss-Coray says two proteins stood out. One rose dramatically in people with memory problems, the other fell sharply.

WYSS-CORAY: So we made a ratio between the two, and that ratio turns out to be a very good indicator of whether a person’s memory is OK or not.

HAMILTON: Wyss-Coray says they use the sample to assess spinal fluid samples from people who have a genetic predisposition to Alzheimer’s.

WYSS-CORAY: In these individuals, it goes up 10 to 20 years before they get the actual disease diagnosis correlating with their subtle impairment of cognition.

HAMILTON: Both proteins in the test are involved in maintaining synapses, the connections between neurons. So Dr. Paul Worley of Johns Hopkins University says it makes sense that levels of these proteins change when Alzheimer’s begins to affect brain function.

PAUL WORLEY: The exciting thing here is that this is a process that seems to anticipate the development of cognitive decline 10, 20, 30 years later.

HAMILTON: Worley says that sets the stage for Alzheimer’s treatments that begin long before symptoms appear, and he predicts that future treatments will include drugs that target the brain synapses. Jon Hamilton, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Greetings from Acre, Israel, where an old fortress recalls the time of the Crusades

Far-Flung Postcards is a weekly series in which NPR's international team shares moments from their lives and work around the world.

Can’t decide what to read next? Here are 20 recommendations for your book club

You know that feeling when you finish a book and just have to discuss it with someone? That's a great book club book. Here are 20 tried-and-true titles that are sure to get the conversation started.

The risks of AI in schools outweigh the benefits, report says

A new report warns that AI poses a serious threat to children's cognitive development and emotional well-being.

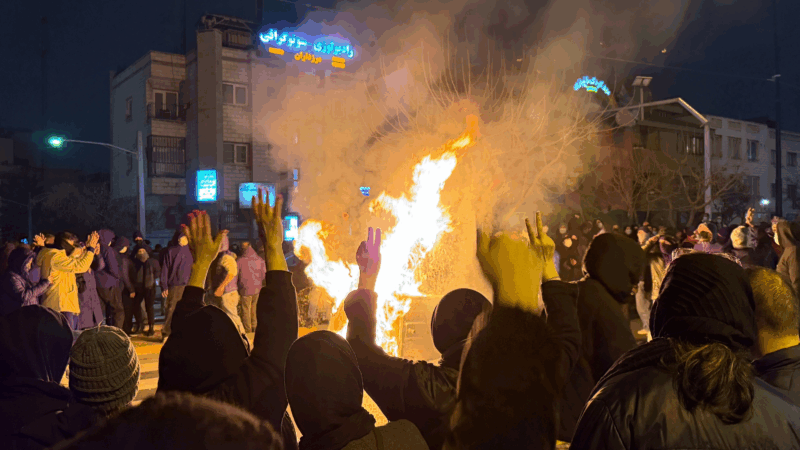

The death toll from a crackdown on protests in Iran jumps to over 2,500, activists say

The number of dead climbed to at least 2,571 early Wednesday, as reported by the U.S.-based Human Rights Activists News Agency, as Iranians made phone calls abroad for the first time in days.

How have prices changed in a year? NPR checked 114 items at Walmart

We found the effects of tariffs and extreme weather, relief (finally!) in the egg cooler, plus one case of shrinkflation.

How the feud between Trump and Minnesota is impacting the probe into the ICE shooting

The FBI is solely leading the inquiry into the killing of Renee Macklin Good by ICE agent Jonathan Ross without help from Minnesota authorities. Legal experts explain why the move is unusual and why joint investigations are the norm.