Jordan’s military is test-running an air bridge for aid to Gaza

AL-QARARA, Gaza Strip — With just five minutes on the ground, Jordanian air force crew members rush to unload cardboard boxes from the back of a Black Hawk helicopter on the tarmac. In the distance, past a wire fence, is the rubble: toppled buildings and concrete shells of damaged high-rise apartments.

Jordan’s Royal Air Force began a new aid operation to Gaza soon after the ceasefire began last month between Israel and Hamas. It has been test-running 16 helicopter flights a day within Israel’s self-declared buffer zone. Delivering aid into Gaza by land still faces considerable obstacles after more than a year of war.

Mission commander Col. Naji Azzam Bani Nasr said the Jordanian operation, which NPR joined last Sunday, was aimed at getting essential medicines to Gaza hospitals.

“Anesthesia, medications for chronic diseases — these are the things they lack in Gaza hospitals and they need it very fast,” he said on the tarmac at Jordan’s King Abdullah II airbase. Bani Nasr said as of Feb. 9, the air force had delivered almost 100 tons of aid during the operation.

Jordan operates two field hospitals in Gaza, one established in 2009 and a second which began operating after the start of the Gaza war in October 2023.

Touching down in southern Gaza during the first Jordanian air lift of the day, the concrete landing field within Israel’s self-declared buffer zone was empty. Beyond a fence, three trucks were waiting to be loaded. As each flight unloaded, another was poised to land.

NPR was not allowed to take photographs from the ground of the destruction — a ban imposed by Israel, Jordanian military officials said. But the extent of the devastation was clearly visible from the air.

Over Israel, bright-green farm fields and communities with swimming pools dotted the landscape. From the air, the pale blue of the Mediterranean Sea was the only spot of color crossing into Gaza, where destroyed and damaged concrete buildings were a bleak palette of gray.

Sunday’s trip was a rare glimpse for foreign journalists on the ground in the devastated Palestinian territory. Gaza-based Palestinian journalists have covered the war from the start, with 82 journalists killed in 2024 by the Israeli military, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. But Israel largely bans foreign journalists from Gaza. The two-hour flight moved along the Dead Sea that separates Israel from Jordan, over Israel and touched down in southern Gaza, near the town of al-Qarara.

The United Nations says more than two-thirds of Gaza’s buildings have been damaged or destroyed since the war began and 90% of the population displaced. A fragile ceasefire which took effect on Jan. 19 called for Israel to increase the number of aid trucks across its land borders with Gaza, but aid groups say many badly needed medical and fuel supplies remain restricted.

“We started using land routes when we could but sometimes there is a need for some commodities like medicine, some equipment and some high-value food items for children we need to get to Gaza quickly,” says Hussein Shibli, director of the Jordan Hashemite Charity Organization, which organizes the aid shipments with the military.

Jordan, along with other countries, had previously dropped aid pallets with parachutes from cargo planes over Gaza. But the drops were dependent on weather, with some landing in the sea. At least 20 people either drowned trying to retrieve the aid or were killed when pallets landed on them, according to Gaza health authorities.

It is also difficult to ensure distribution to those who most need the aid with regular air drops.

Jordan is a key U.S. security partner. Many of the Jordanian Black Hawk pilots on the aid mission were trained in the U.S.

Each Black Hawk can carry one ton of cargo — far less than the roughly 20 tons a truck can carry — and flying in aid is much more expensive. Air shipments, like aid delivered by truck, must still be cleared in advance by Israeli authorities.

Shibli said Jordan was considering whether to continue the air bridge to supplement land deliveries. Jordanian authorities say this Sunday’s flights will be the last in the test program, and it’s unclear when they may resume.

Transcript:

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

The fragile ceasefire between Israel and Hamas has allowed desperately needed food and medicine to enter Gaza. The country of Jordan has started a test program to send military helicopters carrying medical aid into Gaza. NPR’s Jane Arraf joined the Jordanian military on one of those flights.

(SOUNDBITE OF PLANE ENGINE WHIRRING)

JANE ARRAF, BYLINE: At the King Abdullah II air base outside of Amman, helicopter crews are on the tarmac, loading supplies in what has been a test run for getting more aid into Gaza.

They’re loading up cardboard boxes into the hold of this Black Hawk helicopter – big Jordanian flags on them. They’re carrying medical aid and things like infant formula.

Jordan has been conducting air drops into Gaza for more than a year, but those were pallets with parachutes pushed out of cargo planes, and they didn’t always land where they were supposed to.

(SOUNDBITE OF HELICOPTER BLADES SPINNING)

ARRAF: These flights – 16 a day for eight days – are exploring whether landing the aircraft in Gaza and handing supplies over on the ground is a better option. We climb in, sitting on cardboard boxes of medical supplies.

UNIDENTIFIED PILOT: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: Cleared for takeoff, the pilot lifts off for the two-hour flight, part of it along the Dead Sea that separates Jordan from Israel.

(SOUNDBITE OF HELICOPTER BLADES SPINNING)

ARRAF: In Israel, we fly over communities with swimming pools, green farm fields, and then crossing into Gaza, there’s almost no color.

We’ve just landed in Gaza – not very far into Gaza, just a few hundred feet beyond the fence. It’s part of the buffer zone that Israel has created. There is not another person in sight here, but just down the road, we can see trucks that are presumably waiting to load up with these supplies.

(SOUNDBITE OF HELICOPTER BLADES SPINNING)

ARRAF: It’s a very rare glimpse of Gaza on the ground. Local journalists have covered the war at great risk since it began, but Israel, for the most part, bans foreign journalists from here. It takes less than five minutes to unload. Not the easiest or cost-effective way to bring in aid, but with so much need here, Jordan says, still a necessary one. Jane Arraf, NPR News, near Deir al-Balah, Gaza.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

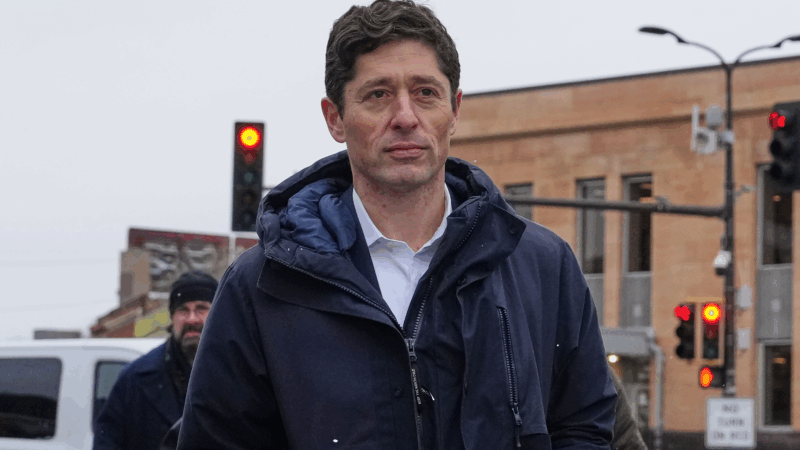

Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey have been subpoenaed by the DOJ

The Minnesota attorney general and St. Paul mayor have also been subpoenaed as local, state and federal officials have clashed in the aftermath of the shooting of Renee Good by an ICE agent.

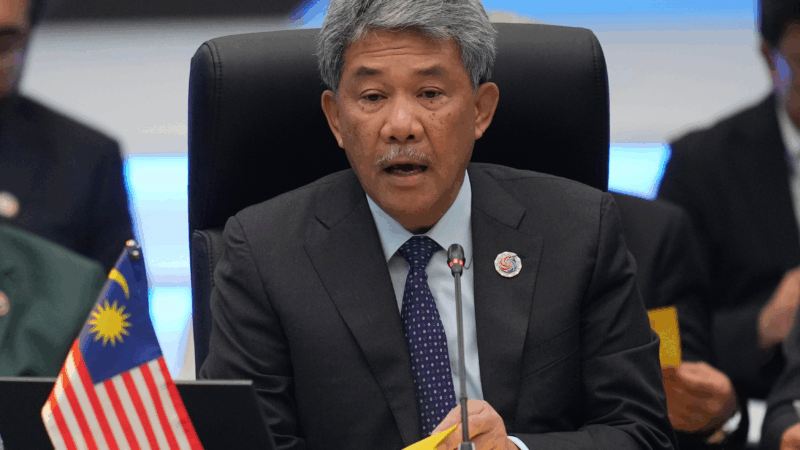

ASEAN won’t endorse election in military-ruled Myanmar, Malaysia says

Malaysia's foreign minister Mohamad Hasan cited concerns over the lack of inclusive and free participation.

‘The miracle’: A 6-year-old walked away from the train wreck that killed her family

Her parents, brother and cousin were killed in the collision, but the girl was found walking barefoot on the tracks. She's being cared for by grandparents after receiving three stitches in her head.

Trump says U.K. return of Chagos Islands to Mauritius is a reason to acquire Greenland

The president previously supported Britain's agreement to hand back sovereignty of the Indian Ocean archipelago, where the U.K. continues to lease the U.S.-U.K. Diego Garcia military base.

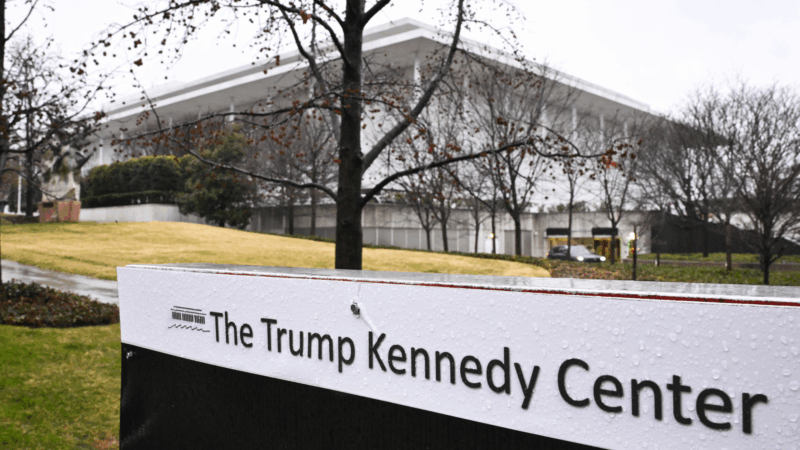

Here’s who’s canceled their Kennedy Center performances since Trump took over

The Martha Graham Dance Company is just the latest to say they will no longer perform at the Kennedy Center since Trump took over last year.

An Alabama mayor signed an NDA with a data center developer. Read it here.

The non-disclosure agreement was a major sticking point in a lively town hall that featured city officials, data center representatives and more than a hundred frustrated residents.