How the pandemic changed the world of disease control for worse — and for better

People who don’t trust scientists.

Nations that don’t trust each other.

And a lab in a suitcase.

These are some of the ways the world has changed – for worse and for better – in the wake of the pandemic.

This week marks the fifth anniversary of the World Health Organization declaring COVID-19 a pandemic. As the SARS-CoV-2 virus quickly spread around the globe, weaknesses in the world’s ability to respond to an infectious disease outbreak became apparent – from an inability to get critical medical supplies to those in need to limits on tracking the disease.

In 2025, how prepared are we if and when the next pandemic strikes?

What’s better

The power of a suitcase lab: For years, something has irked Erik Karlsson. He hates that scientists don’t have a better handle on what diseases are circulating in a population, whether it’s a new virus or one that regularly makes the rounds.

Getting that type of data is “expensive. It’s difficult. And it takes a long time,” says Karlsson, who is the head of the Virology Unit at Institut Pasteur in Cambodia. “We’re finding things maybe a week or two weeks or even a month later.”

Meanwhile, the virus is evolving and moving to new locations. “A lot of times we’re on the back foot,” he says.

COVID highlighted this problem. The medical community couldn’t keep up with the virus – for example, an analysis in the journal Science from 2021 found SARS-CoV-2 was circulating as much as two months before the first case was identified in Wuhan, China.

So Karlsson’s team has spent the past few years building and testing a method to rapidly track what diseases are around. They created a lab-in-a-suitcase. The idea of a mobile lab or portable science station is not new, but Karlsson’s team has worked so their version can get highly specific virus information really quickly.

“We’re now ahead of the game,” Karlsson says. “We’re now detecting things almost in real time.”

His lab looks like a typical carry-on — “on wheels with a handle.” Open it up and you’ll see: “We have a laptop, we have a sequencer [to decode the genome], we have a rice cooker that we use to make gels,” Karlsson explains. “We can actually unpack it and have it ready to test in about five minutes.”

His team – lead by his postdoctoral researcher Anna Fomsgaard – has used this mobile laboratory system to test for diseases among poultry raised in backyards, and they plan to take it to wet markets where live animals are sold for food (and disease can spill over from animals to people) and in rural hospitals (where obscure new viruses might be present).

The suitcase’s superpower is, first, that a swab placed into a little test tube can simultaneously test for multiple diseases.

“My primer can pick up dengue, plus chikungunya, plus Zika, plus Japanese encephalitis,” he says – and several other diseases.

What’s more, this lab can give the genetic code of the virus while still in the field. Is this human flu or avian flu — or something entirely new? “Within 20 minutes, we’re already understanding what viruses are in that sample,” he says.

Each lab-in-a-suitcase costs about $40,000, which is a lot cheaper than setting up a brick-and-mortar lab, where a single PCR diagnostic machine can sometimes cost $30,000.

Checking wastewater and more: These kinds of advances in disease surveillance are happening all over the world.

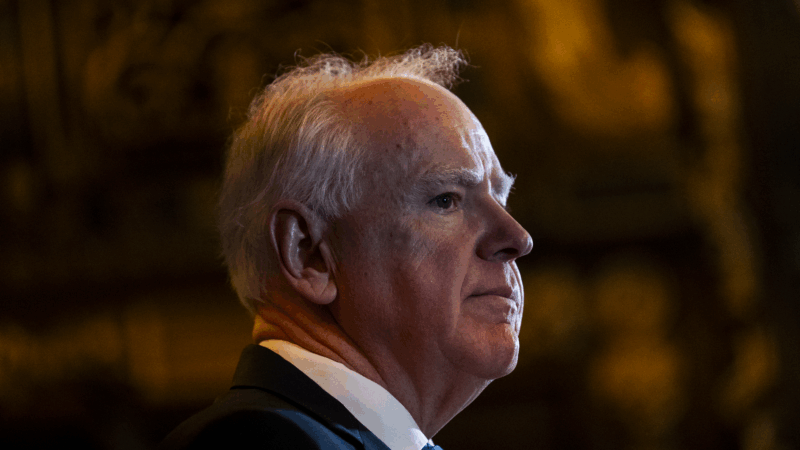

Dr. Paul Friedrichs, who ran the White House Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy under President Biden and was a chief medical adviser for the military during COVID, says this progress is evident in the U.S. He points to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is now using wastewater samples to see what diseases are circulating and automatically collecting data from electronic health records and emergency rooms.

“If you look at where they were in 2019, and where they are today, they’ve made huge improvements in their ability to see what’s happening here in the United States,” he says.

Fredriches worries that recent cuts to foreign assistance are hurting disease detection efforts but still counts the progress made as one of the major successes since the early days of COVID.

Linking up: Scientists from Karlsson in Cambodia to Akan Otu in London and Nigeria say the pandemic helped forge connections across continents and scientific fields.

For example, Otu — who studies plant and animal health and is a senior lecturer at the University of Calabar, Nigeria — says that within the scientific community there’s a new “distinct appreciation” for the need for collaboration across borders. He says folks working in agriculture and veterinary fields are much more integrated with those focused on human health than just five years ago.

“I think COVID has helped us to understand that we should not work in silos,” he says.

But, Fredrichs says, the value of all that work and data depends on how receptive the public is when there’s a health crisis.

What’s worse

Mistrust in science: A Pew Research Center survey found that – during COVID – more than a quarter of Americans were not confident that scientists were working in the public’s interest. And, as of October 2024, some 24% of the American adults had “not too much” confidence in scientists or “none at all” – compared to 13% pre-pandemic.

The lack of public trust has Friedrichs worried. He says it’s his biggest concern when thinking about the next pandemic because without the public’s confidence it’s hard to implement public health measures.

“You can build the perfect test, and if you just walk out and say, ‘I built the perfect test’ and people don’t trust you, they’re not going to use it, and then it doesn’t matter if it was perfect,” he says.

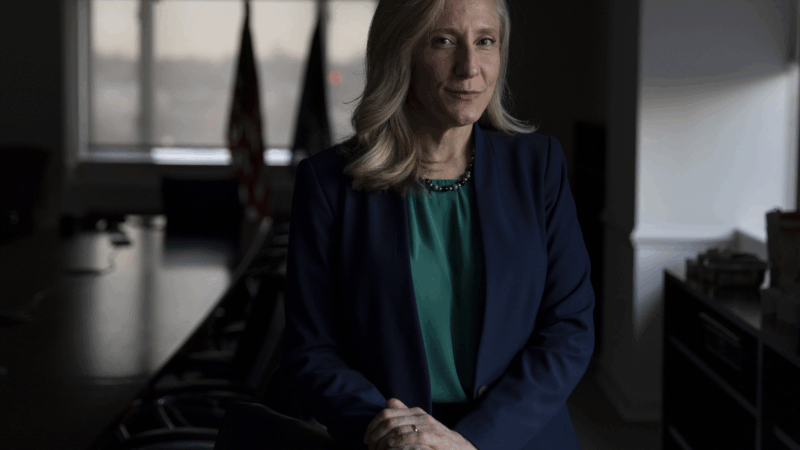

Dr. Luciana Borio says she understands what’s behind the drop in public trust. Borio served in the first Trump White House for three years as director for medical and biodefense preparedness and is now a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations. She says, during COVID, many people felt as if they couldn’t openly express their skepticism about pandemic responses like vaccines and lockdowns.

“We confused facts and values, and sometimes we thought we were arguing over facts, when in fact, we were arguing over values,” she says.

For example, she says, supporters of vaccine mandates felt they were 100% right – and opposing voices were absolutely wrong. “Anybody opposing the prevailing views, they were kind of ostracized and not invited to the scientific debate,” she says, adding that only increased the distrust of health authorities.

Countries aren’t getting along: The pandemic also sowed distrust between countries.

China didn’t share relevant data on COVID. Many low- and middle-income countries watched as wealthier nations received vaccines and medications first.

“It was a very desperate situation,” remembers Hadley Sultani Matendechero, deputy director general for health in Kenya. “[Vaccines] in our minds were the only antidote to this catastrophe, but we were not able to access them.”

One major effort to fix the lack of trust that emerged from the COVID pandemic has been the Pandemic Treaty, an international agreement between over 190 countries on how to collaborate and share resources.

But, for several years, negotiations have faltered with a major challenge being whether high-income countries will share diagnostics, medications and vaccines in exchange for disease information from low- and middle-income countries when there’s a health emergency.

And then in January of this year there seemed to be a new setback. President Trump pulled out of the talks altogether as part of his executive order starting the process of withdrawing the U.S. from the World Health Organization because of its “mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic … and its inability to demonstrate independence from the inappropriate political influence.”

Many observers thought this move would essentially be a death knell for the Pandemic Treaty, “blowing it up,” says Lawrence Gostin, a professor of global health law at Georgetown Law and director of the World Health Organization’s Center on Global Health Law.

But it didn’t.

“In a perverse way, President Trump’s withdrawal from the negotiations has energized much of the rest of the world to get this done,” he says.

As the U.S. sits on the sidelines, Gostin worries, “as an American, I feel naked, unprotected.”

Transcript:

A MARTÍNEZ, HOST:

Five years ago this week, COVID-19 was declared a pandemic. And as the virus spread, it became apparent how little the world knew about protecting itself from a serious global outbreak. NPR’s Gabrielle Emanuel reports that since then, some things have gotten better, others have gotten worse.

GABRIELLE EMANUEL, BYLINE: Erik Karlsson can tell you what’s getting better. For years, he’s been frustrated by how long it can take from when a disease first strikes to when scientists can identify it and respond.

ERIK KARLSSON: A lot of times we’re on the back foot. We’re finding things maybe a week or two weeks or even a month later.

EMANUEL: Karlsson is the director of the National Influenza Center of Cambodia. He says COVID highlighted this problem, and he spent the past few years working on how to get disease information in real time.

KARLSSON: What we’ve done is really put together what we call kind of a lab in a suitcase.

EMANUEL: Open it up and…

KARLSSON: We have a laptop. We have a sequencer, a rice cooker that we use to make gels. We can actually unpack it and have it ready to test in about five minutes.

EMANUEL: They’ve used it on poultry farms and plan to take it to wet markets and rural hospitals. One swab can test for multiple diseases.

KARLSSON: Dengue plus chikungunya, plus Zika, plus Japanese encephalitis, plus…

EMANUEL: COVID, flu, rabies. And he can get the genetic code. Is this human flu or avian flu, or something entirely new?

KARLSSON: Within 20 minutes, we’re already understanding what viruses are in that sample. We are now ahead of the game.

EMANUEL: Advances in disease surveillance are happening all over the world, including here in the U.S. Paul Friedrichs was a chief medical adviser for the military during COVID. He says the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention deserve credit.

PAUL FRIEDRICHS: If you look at where they were in 2019 and where they are today, they’ve made huge improvements in their ability to see what’s happening here in the United States.

EMANUEL: They’re doing things like sampling wastewater to see what diseases are circulating.

FRIEDRICHS: Collecting data automatically from electronic health records, from emergency rooms.

EMANUEL: But Friedrich says all that data isn’t valuable without this, the public’s trust. In fact, that’s his biggest concern when thinking about the next pandemic.

FRIEDRICHS: You can have the best surveillance system in the world. You can build the perfect test. And if you just walk out and say I built the perfect test and people don’t trust you, they’re not going to use it. And then it doesn’t matter if it was perfect.

EMANUEL: A Pew Research study found that during COVID, more than a quarter of Americans said they didn’t trust scientists to act in the public’s best interest. And still today, that public trust remains below pre-pandemic levels. Luciana Borio says she understands why. Borio served in the first Trump White House as director for medical and biodefense preparedness. She says, during COVID, patients told her they couldn’t openly express their skepticism about things like vaccines and lockdowns.

LUCIANA BORIO: Anybody opposing the prevailing views, they were ostracized and not invited to the scientific debate.

EMANUEL: Which, she says, made people more distrustful of health authorities. The pandemic also sowed distrust between countries. China didn’t share relevant data on COVID. Many low- and middle-income countries watched as wealthier nations got COVID vaccines and medications first. One major effort to fix the issues that emerged is the pandemic treaty. But international negotiations have faltered. And then in January of this year, President Trump pulled out of the talks altogether. Lawrence Gostin at Georgetown Law thought now the whole thing is going to blow up, but it didn’t.

LAWRENCE GOSTIN: In a perverse way, President Trump’s withdrawal from the negotiations and from WHO has energized much of the rest of the world to get this done.

EMANUEL: As the U.S. now sits on the sidelines, Gostin worries. If there isn’t trust and cooperation between nations, he says, it’s going to be much harder to protect ourselves in the next pandemic.

Gabrielle Emanuel, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF LONESOME ACE STRINGBAND’S “CROSSING THE JUNCTION/DEER RIVER”)

Judge rules immigration officers in Minneapolis can’t detain peaceful protesters

Officers in the Minneapolis-area participating in a U.S. immigration enforcement operation can't detain or tear gas peaceful protesters who aren't obstructing authorities, a judge ruled Friday.

Justice Department opens investigation into Minnesota governor and Minneapolis mayor

Federal prosecutors are investigating Gov. Tim Walz and Mayor Jacob Frey.

No sign of new protests in Iran as a hard-line cleric calls for executions

A Iran returns to an uneasy calm after protests led to a violent crackdown, a senior cleric is calling for the death penalty for detained demonstrators. His sermon Friday also threatened U.S. President Trump.

Gulf South food banks look back on a challenging year as another shutdown looms

Federal funding cuts and a 43-day government shutdown made 2025 a chaotic year for Gulf South food banks. For many, the challenges provide a road map for 2026.

Measles is spreading fast in S.C. Here’s what it says about vaccine exemptions

More than 550 people have contracted measles in Spartanburg County, S.C., in a fast-growing outbreak. Like a majority of U.S. counties, nonmedical exemptions to school vaccination are also rising.

It took 75 governors to elect a woman. Spanberger will soon be at Virginia’s helm

Abigail Spanberger, a former CIA officer and three-term congresswoman, is breaking long-held traditions on inauguration day. She says she wants her swearing-in to showcase the state's modern vibrancy.