He fled Syria’s war as a teenager. He went back to help launch a tech industry

DAMASCUS, Syria — Abdulwahab Omira escaped Syria’s civil war with his family as a teenager, shortly after he was freed from prison, having witnessed terrible abuses by the former regime.

Now a U.S. citizen, he recently returned to Syria as a Stanford graduate student and a budding entrepreneur, hoping to help jump-start a tech industry in a country still struggling to find equilibrium after 14 years of devastating conflict.

President Bashar al-Assad was ousted in December, but Syria is still wracked by spasms of violence, as well as millions of citizens who’ve lost their homes, their livelihoods and most everything else. But occasional glimmers of hope appear, like a recent tech conference that brought together hundreds of young Syrians, and a small number of Syrian-Americans, including Omira, at a Sheraton Hotel ballroom in the capital Damascus.

“Everyone is excited. We want to build. We want to do something for our country,” said Omira, 28, who took a break from his master’s program in artificial intelligence at Stanford to attend.

The event, dubbed Sync ’25: Silicon Valley + Syria, was convened by Syrian-American technologists and entrepreneurs to explore ways that tech might help Syria rebuild. Like everyone at the conference, Omira acknowledged the staggering challenges.

“There’s no infrastructure, there is no electricity, there is no water, there’s no internet,” he said. “Showering is an event.”

Omira said his own experience taught him resilience, and he believes many Syrians have learned the same lesson.

Imprisoned at age 14

As a precocious teenager in Damascus, he studied the high cancer rates in an area where the Syrian government disposed of nuclear waste.

He proposed a new method for handling the waste and was awarded a patent at age 14. That was followed with an invitation to be honored at the presidential palace in 2012.

But before that took place, Omira was stopped on the street one day by members of the feared intelligence service. Omira had been working with a professor on the nuclear waste project, and was carrying a document related to the nuclear program. When the security forces found the paper, they tossed Omira in prison.

The experience was harrowing.

“They start bringing people in, killing them under torture, showing me how they kill them,” he said. “Each room had a different theme of killing. There’s so much horrible stuff, like room number three, where they killed people with a chainsaw.”

Omira said he was not physically harmed. But he was warned that if he was arrested again, “You will choose one of those rooms to die in.”

He was released after two months, and his family decided it was time to leave Syria. The Syrian civil war had erupted a year earlier, in 2011, prompting millions to flee, and it was increasingly clear that no one in the country was safe.

The Omira family went from a prosperous life in Damascus to a tent in a refugee camp in neighboring Turkey, where they would remain for several years. Eventually, they made it to the United States, landing in Chicago in 2016.

But Omira didn’t speak English or have a valid high-school diploma. He got a high-school equivalency, a GED certificate, and kept studying until he got a perfect score on the ACT college entrance exam -– and admission at Stanford.

He graduated with a computer science degree last year, and is now working on his master’s in artificial intelligence.

He runs a tech startup, called Farmitix, designed to help farmers in Syria and elsewhere. During his recent trip to Syria, he met with tech students at seven universities throughout the country.

Using tech to rebuild a broken country

Still, the obstacles can seem overwhelming.

For starters, there’s the daily challenge of getting electricity and an internet connection. Many young Syrian tech students want to learn more about AI. But U.S. products, like ChatGPT, are not easily available due to comprehensive U.S. sanctions. So Syrians say they’re learning on DeepSeek, a Chinese model.

The U.S. sanctions were imposed against Syria’s longtime dictator, Assad, and his regime. He was ousted in December, but the sanctions have not been lifted, and there’s no sign they will be any time soon.

This was a recurring theme at the recent tech conference.

“The sanctions now are quite prohibitive. The banking system is disconnected from the rest of the world. And so folks like me can never invest in Syria until these sanctions are lifted,” said Rama Chakaki, a Syrian-American and a tech investor from Southern California who organized the conference.

For now, the goal is to connect to Syria’s tech community, which was so isolated during the war.

“One thing about Syrians is we’re very socially interconnected,” said Chakaki. “All of us, having been in the diaspora, feeling very displaced, couldn’t wait for that chance to get together. So my 12,000 connections on LinkedIn worked really well for me.”

When Abdulwahab Omira returned to Syria, he visited his old family home in the capital, which was destroyed by the fighting.

“I went to my room. I was digging out my memories. And then I found a computer science book that I got in seventh grade,” he said. “They were explaining what the internet is, how to use the keyboard, how to turn off the PC.”

Omira has come a long way since then. He summed up his journey, from refugee to Stanford student to tech entrepreneur.

“The U.S. is definitely the land of opportunity. If you put in 100%, you get 100%,” he said. “In Turkey, if you put in 100%, you probably will get 10%. Here in Syria, if you put in 100%, you get put in prison.”

He’s hoping to write a new formula for a new Syria.

NPR’s Jawad Rizkallah contributed to this report.

Transcript:

MARY LOUISE KELLY, HOST:

Syria is still struggling three months after its revolution. There are glimmers of hope. At one hotel, hundreds of people recently gathered to talk about jump-starting the country’s tech industry, which was virtually nonexistent during Syria’s civil war. One young man fled that war as a teenager. He returned as a Stanford grad student and a budding entrepreneur. NPR’s Greg Myre has the story from the capital, Damascus. And a warning – this piece does include descriptions of torture and abuse.

GREG MYRE, BYLINE: Some 700 people – most from Syria and some from the U.S. – filled a ballroom at the Sheraton Hotel in Damascus for the tech conference dubbed Silicon Valley in Syria.

ABDULWAHAB OMIRA: Everyone was here, and everyone is excited. Everyone, like – you know, this excitement of like, hey, we want to build. We want to do something for our country. We’re so happy.

MYRE: Abdulwahab Omira is a young Syrian American who took a break from his master’s program at Stanford to attend. Like everyone at the conference, he acknowledged the staggering challenges after 14 years of civil war.

OMIRA: There’s no infrastructure. There is no electricity. There is no water. There’s no internet. Showering is an event.

MYRE: Omira says his own experience taught him resilience, and he believes many Syrians have learned the same lesson. As a teenager in Damascus, he studied the high cancer rates in an area where the Syrian government disposed of nuclear waste. He proposed a new method and was awarded a patent at age 14 and was supposed to be honored at the presidential palace. But before that happened, he was stopped one day by the security forces. They found documents related to the nuclear program, and Omira was tossed in prison. The experience was harrowing.

OMIRA: They start bringing people in, killing them under torture, showing me how they killed them. And each room has a different theme of killing – so many horrible stuff. Like, room No. 3, for example, they killed people with, like, a chainsaw.

MYRE: Omira was not physically harmed, but he was warned that if he was arrested again…

OMIRA: You will choose one of those rooms to die in.

MYRE: Omira was released after two months, and his family decided it was time to leave Syria. They went from a prosperous life in Damascus to a tent in a refugee camp in neighboring Turkey. Eventually, they made it to the U.S., landing in Chicago. But Omira didn’t speak English or have a valid high school diploma. He kept studying until he got a perfect score on the college entrance exam and admission to Stanford University. He graduated with a computer science degree last year. He’s now in the masters program, working on artificial intelligence. He also runs a tech startup designed to help farmers in Syria. And he’s meeting with tech students throughout the country.

OMIRA: We went to seven universities across Syria where we give workshops for the students.

MYRE: Still, the obstacles in Syria can seem endless. U.S. sanctions remain. They were imposed against Syria’s dictator, Bashar al-Assad, and though he was ousted three months ago, the sanctions have not been lifted. This was a recurring theme at the tech conference. Organizer Rama Chakaki is a Syrian American and a tech investor from California.

RAMA CHAKAKI: Absolutely. So the sanctions now are quite prohibitive. I mean, the banking system is disconnected from the rest of the world. And so folks like me can never invest in Syria until these sanctions are lifted.

MYRE: For now, the goal is to connect Syria’s tech community, which was so isolated during the war.

CHAKAKI: One thing about Syrians is we’re very socially interconnected. All of us having been in the diaspora, feeling very displaced, couldn’t wait for that chance to get together. So my 12,000 connections on LinkedIn worked really well for me.

MYRE: When Abdulwahab Omira returned to Syria, he visited his old family home.

OMIRA: I went to my room. I was digging out my memories, and then I found my first CS book – computer science book – that I got in seventh grade. They were explaining what the internet is, how to use the keyboard, how to turn off the PC.

MYRE: Omira has come a long way since then. He summed up his journey from refugee to Stanford student to tech entrepreneur this way.

OMIRA: The U.S. was definitely the land of opportunity because if you put, like, 100%, you get 100%. In Turkey, if you put 100%, you get probably, like, get 10%. Here if you put 100%, you get in prison.

MYRE: He’s hoping to write a new formula for a new Syria.

Greg Myre, NPR News, Damascus.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

New York Giants hire John Harbaugh as coach after identifying him as their top choice

Harbaugh joins the Giants 11 days after he was fired by the Baltimore Ravens. The Super Bowl champion is now tasked with turning around a beleaguered franchise.

US launches new retaliatory strike in Syria, killing leader tied to deadly Islamic State ambush

A third round of retaliatory strikes by the U.S. in Syria has resulted in the death of an Al-Qaeda-affiliated leader, said U.S. Central Command.

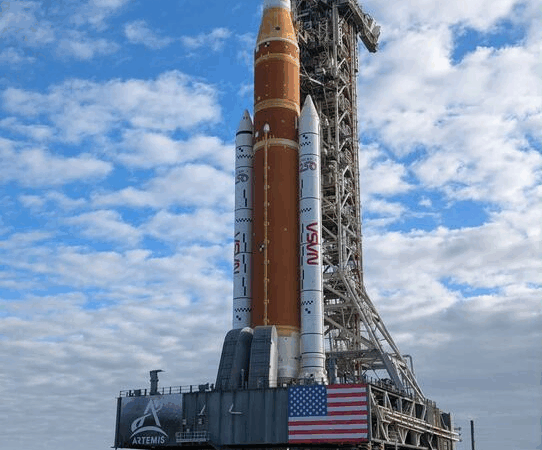

NASA rolls out Artemis II craft ahead of crewed lunar orbit

Mission Artemis plans to send Americans to the moon for the first time since the Nixon administration.

Trump says 8 EU countries to be charged 10% tariff for opposing US control of Greenland

In a post on social media, Trump said a 10% tariff will take effect on Feb. 1, and will climb to 25% on June 1 if a deal is not in place for the United States to purchase Greenland.

‘Not for sale’: massive protest in Copenhagen against Trump’s desire to acquire Greenland

Thousands of people rallied in Copenhagen to push back on President Trump's rhetoric that the U.S. should acquire Greenland.

Uganda’s longtime leader declared winner in disputed vote

Museveni claims victory in Uganda's contested election as opposition leader Bobi Wine goes into hiding amid chaos, violence and accusations of fraud.