Green card holders’ rights in spotlight after arrest of pro-Palestinian activist

A New York federal judge is set to hear pivotal questions in the case of Mahmoud Khalil, a leader of large Gaza solidarity protests at Columbia University who now faces deportation after his arrest by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents.

Khalil, who holds a green card as a legal permanent U.S. resident, isn’t charged with a crime. But the Trump administration says he should be deported because of his protest activity, which it equates with anti-Semitism and support for terrorism.

ICE agents arrested the pro-Palestinian activist at his university-owned apartment building in New York City on Saturday. Khalil recently finished his master’s degree from Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs. He’s now being held in the Jena/LaSalle Detention Facility in Jena, La. — more than 1,000 miles from the home he shares with his wife, a U.S. citizen who is eight months pregnant.

Khalil’s lawyers have filed a habeas corpus challenge to his detention; District Judge Jesse Furman set a hearing for Wednesday, ordering that Khalil “shall not be removed from the United States unless and until” the court rules otherwise.

The high-profile arrest comes after President Trump’s administration said it would deport international college students who protested against Israel and the war in Gaza on campuses last year.

Immigration law experts spoke with NPR about the case and why Khalil’s status as a green card holder is significant.

What rights do green card holders have?

Attaining lawful permanent resident status in the U.S., widely known as getting a green card, confers many rights.

“You’re not a U.S. citizen, but you’re the next level down, meaning that you have the rights to live, work, travel in the United States,” says Kelli Stump, president of the American Immigration Lawyers Association.

Green card holders also have the right to free speech, according to David Cole, a Georgetown Law professor.

“The First Amendment does not distinguish between citizens and non-citizens,” says Cole, who successfully represented Palestinian clients in a lengthy First Amendment case.

“Therefore, since you couldn’t punish a citizen for their speech, you couldn’t deport a foreign national for their speech.”

Green card status can be revoked — as in cases where someone has obtained that status by fraud, or they commit serious crimes. The government also has broad powers under anti-terrorism laws, including the ability to block entry or remove a non-citizen.

“I do think, for people who are non-citizens, there’s some risk in protesting depending on how the protest is interpreted,” says Jason Dzubow, a partner at Murray Osorio, an immigration law firm in Washington, D.C.

“And the reason for that is because the anti-terrorism provisions are just so broad.”

In his view, it’s unclear exactly where the government might draw a line between publicly espousing pro-Palestinian views and what it views as supporting terrorism.

“This is a really a chilling message that the government is sending,” Dzubow says.

To strip someone of their green card, the government has to go through a legal process, according to Stump.

“Only the immigration judge can take that green card away from you in these specific types of removal proceedings,” she says.

In an immigration court, Stump adds, “the government bears the burden of proving the reason that this person is deportable from the United States. And then just depending on what ground we’re looking at, that’s where the fight ensues.”

What is the government’s position?

While some details about the case aren’t yet known, the Trump administration’s statements about Khalil so far suggest that its move is based on allegations that his protest activity amounts to support for Hamas, which they argue is grounds for deportation.

Department of Homeland Security spokesperson Tricia McLaughlin says the agency alleges that the former graduate student “led activities aligned to Hamas, a designated terrorist organization.”

Trump’s Jan. 20 executive order promised to deport international students if they were found to have espoused anti-Semitism. In a post to social media on Monday, the president called Khalil “a Radical Foreign Pro-Hamas Student.”

One detail that could prove crucial in court is Khalil’s green card status. His attorney, Amy Greer, told NPR that ICE agents who arrested him initially told her his student visa had been revoked. When informed that Khalil was a lawful permanent resident, the agents told Greer that that status was being revoked.

Trump said Khalil’s case is the first of many to come. He vowed, “We will find, apprehend, and deport these terrorist sympathizers from our country — never to return again.”

Why is it significant that this is a civil case, not a criminal one?

“The government has a lot of power over non-citizens in terms of how it charges them under the immigration law, which is a civil law, not a criminal law,” Dzubow says. “There’s less defenses.”

A civil case might not sound as imposing as a criminal case. But the stakes can often be just as high — and under civil law, defendants have fewer legal rights than they would in a criminal case, he says.

Such detainees don’t have the right to an attorney, for instance, meaning that while they can pay for their own lawyer, the government isn’t obliged to provide them with one.

“There’s just less protection available” for a green card holder like Khalil, Dzubow says. “And he doesn’t need a criminal conviction to be deported for supposedly espousing terrorist activity.”

Why is Khalil being held in Louisiana?

“It’s typical” for the U.S. to move a detainee to a state far from their residence, says Dzubow.

“What they do is make it very difficult to defend yourself,” he says of the government’s tactics.

The distance isolates detainees from loved ones, support systems and lawyers, Dzubow says, making it a bigger challenge to gather evidence and witnesses that might help a detainee’s case.

He also suggested the move could be a type of what’s called “forum shopping,” in which a party seeks a favorable court venue. In a deportation case, for instance, lawyers might consult the TRAC Immigration website which tracks how frequently immigration judges deny asylum claims.

Republicans say Clintons risk contempt of Congress for not testifying on Epstein

House Republicans are seeking testimony as part of their investigation into convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. The Clintons say they've already provided in writing what little they know.

FTC accuses AI search engine of ‘rampant consumer deception’

Federal officials say a company that operates hundreds of landing pages for AI answers is running an operation that has duped thousands of users, who were unable to stop costly monthly charges.

‘My role was making movies that mattered,’ says Jodie Foster, as ‘Taxi Driver’ turns 50

Foster was just 12 years old when she starred in the 1976 film. "What luck to have been part of that, our golden age of cinema in the '70s," she says. Her latest film is Vie Privée (A Private Life).

Supreme Court appears likely to uphold state bans on transgender athletes

To date, 27 states have enacted laws barring transgender participation in sports.

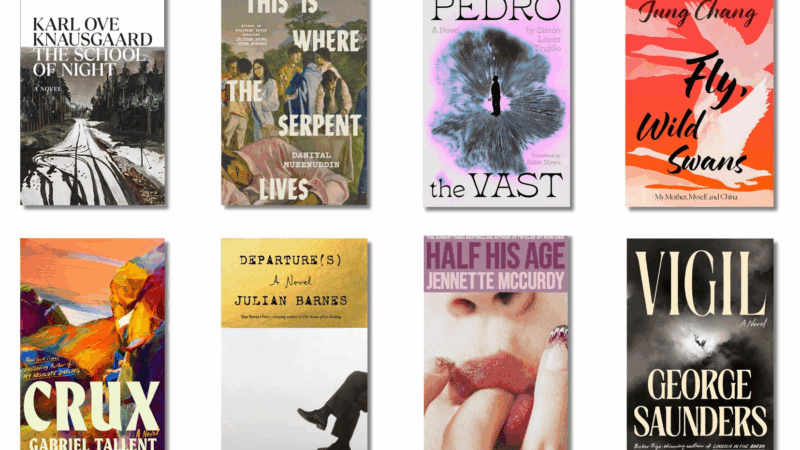

Keep an eye out for these new books from big names in January

The new year begins with a host of promising titles from George Saunders, Julian Barnes, Jennette McCurdy, Karl Ove Knausgaard and more. Here's a look ahead at what's publishing this month.

Want to play a Tiny Desk concert? The 2026 Contest is now open for entries

The 2026 Tiny Desk Contest, our annual search for the next great undiscovered artist, is now officially open for entries.