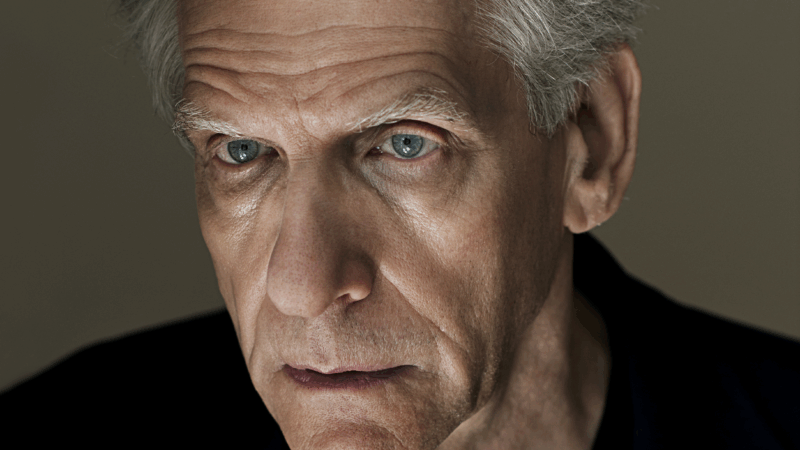

David Cronenberg’s grief is “as powerful as it always was”

The loss of a loved one can shroud one’s life in darkness that seemingly consumes everything around them. Some may drown in their grief, and yet others may ask “how dark do I want to go?”

In The Shrouds, Karsh, played by Vincent Cassel, loses his wife and can’t let her decompose alone.

“When they lowered my wife, Becca, into the coffin , I had an intense urge to get into the box with her,” Cassel’s Karsh says to a blind date at the start of the film.

When we meet Karsh, it’s been four years since he lost Becca (one of three parts played by Diane Kruger in this film) to cancer and he can’t bear to let her go. So, he creates a burial shroud technology that allows him to watch her body whither away in the grave.

David Cronenberg told NPR that though the character he wrote still very much feels his wife’s presence, she’s “obviously not physically with him and that’s really what kind of drives him crazy.”

Grief can be a waking nightmare

Although Karsh is able to see Becca’s body – which is mostly skeletal at the point we meet her – he can only speak to her in his dreams. Or, more accurately, nightmares.

“There are moments which I think are quite clearly sort of dream sequences in the movie where he’s not losing his mind, but his unconscious is bringing him the images of himself and his wife,” Cronenberg said.

With each ghostly visit, we see a more disfigured Becca, who becomes increasingly mangled in Karsh’s horrific dreams – she loses a breast, then a lower arm. She’s riddled with surgical scars.

These images “are not exactly realistic,” Cronenberg said, “but [they’re] emotionally realistic moments… and although it’s presented in a sort of dreamlike way, you can understand that in real life, basically, he would have experienced that with her.”

On the loss of his wife

“Well, that, of course, was the impetus for me to start to write the screenplay for this movie. But in a situation like this, when I start to write the screenplay thinking about things that have happened to me in my life, it becomes fiction,” he said.

Cronenberg’s philosophy here is simple: Be inspired by your life, but remember that the characters you’re writing must be different from who you are in real life. That’s despite the fact that Cassel’s Karsh bears an almost eerie resemblance to Cronenberg, and that both Karsh and the director suffered similar losses.

“You want them [the characters] to become alive in their own way and sort of tell you who they are and to say things that you didn’t expect them to say and to do things that you didn’t expect them to do. And when you’re writing a script, you want the characters to do that because it means that… they now have their separate existence,” Cronenberg said.

A morbid technology

The Grave-Tech Karsh invented in The Shrouds is clearly meant to make audiences squirm – as well as other characters. We see a perfectly suitable blind date get spooked by Karsh’s corpse cam at the start of the movie.

But Cronenberg isn’t so sure that people would be entirely turned off by the idea that they can be cadaver voyeurs. In fact, he said that a journalist told him recently that he conducted his own survey of 28 people, asking them whether they would use this technology if it were available.

“Like 11 said they [the surveyed] wouldn’t, but 14 said they would. And I was a little surprised by that. I don’t think I’m the only human being in the world who would maybe do that, but I didn’t think that the ratio would be that close,” Cronenberg said.

“If you’re a religious person and you think that you’re going to meet this person in heaven or something like that, some kind of afterlife, perhaps you would not have an interest in doing this kind of thing. But if you didn’t believe that, if you were really an atheist and you thought there is not going to be any other way to connect with this person other than physically that they exist only physically, then maybe you would have a different attitude.”

When grief becomes objectification

“In my last movie before this one, Crimes of the Future, there is the mantra spoken. It is “body is reality.” And if you believe that [your] body is really your reality, and it’s how you understand reality, then burial suddenly becomes a separation from the reality of that person,” Cronenberg said.

You don’t really learn much about Becca in the film. You only see her in those horror-like dream sequences. Cronenberg said that was by design.

“I deliberately didn’t do the sort of traditional flashback thing about when they first met and when they went on their first vacation and all those things that you usually see in a movie that’s about someone who died, because for him [Karsh], her death was a physical event,” Cronenberg said.

“So he’s naturally focused on what he has left of her, which is, of course, memories. But beyond that, it’s her body. So, yes, I mean, I think people who are in love and aren’t romantically involved, there’s certainly a sense of possession of both of them, of each other’s bodies.”

Can technology help us cheat death?

David Cronenberg didn’t find catharsis in making The Shrouds either, he said filmmaking just isn’t “therapy.” And making this movie, as inspired by his own grief as it may be, certainly didn’t erase it.

The same goes for any attempt to remake a loved one using AI or some other technology.

“It’s [grief] still there, as it always was, just as powerful as it always was. And of course, you have to remember that the deceased is deceased. So that person is not really going to talk to you. It’s a construct that’s talking to you now,” he said.

“For some people, maybe that would help them. And yet, don’t forget, that person is actually dead. So it’s not really helping them in an afterlife. It’s giving you the delusion that the person is still alive.”

The Shrouds is in theaters now.

Transcript:

AYESHA RASCOE, HOST:

The loss of a loved one can shroud one’s life in darkness that seemingly consumes everything around them. Some may drown in their grief, yet others might ask themselves, how dark do I want to go?

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, “THE SHROUDS”)

VINCENT CASSEL: (As Karsh) When they lowered my wife into the coffin, I had an intense urge to get into the box with her.

RASCOE: In “The Shrouds,” Karsh, played by Vincent Cassel, loses his wife and can’t let her decompose alone. So he creates a technology that allows him to watch her body wither away in the grave. “The Shrouds” is written and directed by David Cronenberg, and he joins us now. Welcome to the program.

DAVID CRONENBERG: Thank you. Thanks.

RASCOE: So I want to start with where we find Karsh at the start of the film, not physically but mentally. He lost his wife four years ago, but she’s still very much with him, right?

CRONENBERG: Yes. She’s with him but obviously not physically with him, and that’s really what kind of drives him crazy. And because he’s a high-tech entrepreneur, he sort of looks to technology automatically for some kind of way of grappling with his grief – the grief of the loss of this woman who he’s been with for much of his life.

RASCOE: It seems like the film plays with the audience and what is real and what is not, and is that because that’s the way grief feels?

CRONENBERG: Yeah, but there are moments which I think are quite clearly sort of dream sequences in the movie where he’s not losing his mind, but his dream state, his unconscious is bringing him images of himself and his wife – which are not exactly realistic, but emotionally, they’re realistic – moments when his wife would come back from the hospital and she would be missing an arm, let’s say, or she would have scars from surgery. And although it’s presented in a sort of dreamlike way, you can understand that in real life, basically, he would have experienced that with her.

RASCOE: You lost your wife, Carolyn, to cancer in 2017, and I’m so sorry for your loss.

CRONENBERG: Well, yeah, I mean, that, of course, was the impetus for me to start to write the screenplay for this movie. But in a situation like this, when I start to write the screenplay, thinking about things that have happened to me in my life, it becomes fiction. You are creating fictional characters, and you want them to be different from yourself. You want them to become alive in their own way and sort of tell you who they are and to say things that you didn’t expect them to say and to do things that you didn’t expect them to do. And when you’re writing a script, you want the characters to do that because it means that they have come alive, you know, that they’re – they now have their separate existence.

RASCOE: Does it kind of annoy you that people bring it up?

CRONENBERG: No, it’s a reasonable thing. I mean, if I had not wanted to mention it, I would have not ever talked about the loss of my wife. So I’m just being very frank and very honest about it. And it’s understandable that in an interview situation, for example, or even a review, that people should mention it.

RASCOE: Karsh tells a blind date at the start of the movie that at his wife’s burial, he wanted to jump into the grave with her, and that becomes the inspiration for his voyeuristic grave tech. I get it, but I don’t get it. What – it’s kind of morbid.

CRONENBERG: I talked to a journalist recently who said he did his own survey of about 28 people asking them if they would do this, if they would buy that idea of burying a loved one in this situation, this kind of grave. He said, like, 11 said they wouldn’t, but 14 said they would. And I was a little surprised by that. I don’t think I’m the only human being in the world who would maybe do that, but I didn’t think that the ratio would be that close.

So it’s possible that there are people who, after some speculation, might well do this. I mean, of course, you know, if you’re a religious person, you think that you’re going to meet this person in heaven or something like that, some kind of afterlife, perhaps you would not have an interest in doing this kind of thing. But if you didn’t believe that, if you were really an atheist, and you thought there is not going to be any other way to connect with this person other than physically, that they exist only physically, then maybe you would have a different attitude.

RASCOE: It seems like Karsh – his grief does kind of cross into objectification, like, this kind of ownership of his wife’s body. And is it because the physical body was the tangible thing for him? It was the last thing he could still hold onto?

CRONENBERG: Sure. Absolutely. I mean, in my movie – my last movie before this one, “Crimes Of The Future,” there is the mantra spoken – it is, body is reality. And if you believe that body is really your reality and is how you understand reality, then burial suddenly becomes a separation from that – the reality of that person.

I deliberately didn’t do the sort of traditional flashback thing about when they first met and when they went on their first vacation and all those things that you usually see in a movie that’s about someone who died because for him, her death was a physical event. And so he’s naturally focused on what he has left of her, which is, of course, memories. But beyond that, it’s her body. So, yes, I mean, I think people who are in love and are romantically involved, there’s certainly a sense of possession of both of them, of each other’s bodies.

RASCOE: There is this idea that through technology, maybe people can achieve some sort of immortality if you upload your consciousness or that someone could look at all your movies and look at all your stuff and put it all together and they have a David Cronenberg AI. Like, how do you feel about that? Does that make death different or grief different, you think?

CRONENBERG: No, I don’t think it does at all. And I’m often asked with this movie if it was cathartic and if it helped to alleviate the grief. And my answer was, no, absolutely not. It’s still there as it always was, just as powerful as it always was. And, of course, you have to remember that the deceased is deceased. So there’s not really – that person is not really going to talk to you. It’s an AI construct that’s talking to you now. You might feel that for some people, maybe that would help them. And yet, don’t forget that person is actually dead. So they aren’t really – it’s not really helping them in an afterlife. It’s giving you the delusion that the person is still alive.

RASCOE: What do you think is more creepy, watching someone decompose to connect to them or talking to the AI version of them?

CRONENBERG: I’ll leave it up to you…

RASCOE: OK.

CRONENBERG: …To decide.

RASCOE: (Laughter).

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

RASCOE: That’s director David Cronenberg. His latest film is “The Shrouds.” Thank you so much for speaking with us today.

CRONENBERG: Thank you. Thank you.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

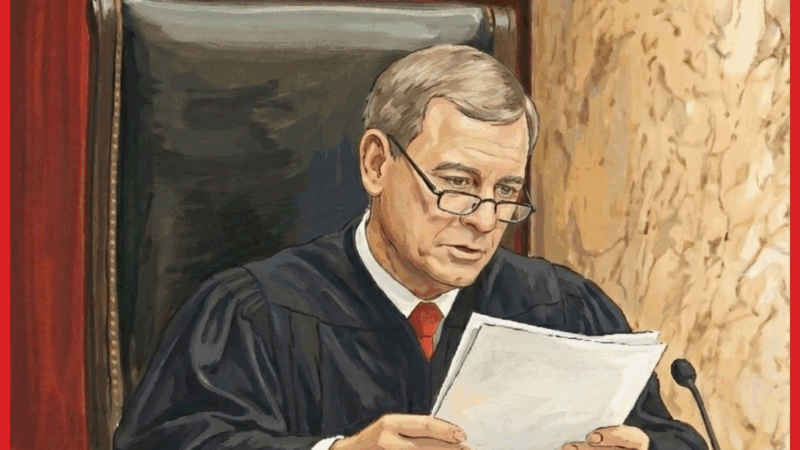

AI brings Supreme Court decisions to life

Like it or not, the justices are about to see AI versions of themselves, speaking words that they spoke in court but that were not heard contemporaneously by anyone except those in the courtroom.

The airspace around El Paso is open again. Why it closed is in dispute

The Federal Aviation Administration abruptly closed the airspace around El Paso, only to reopen it hours later. The bizarre episode pointed to a lack of coordination between the FAA and the Pentagon.

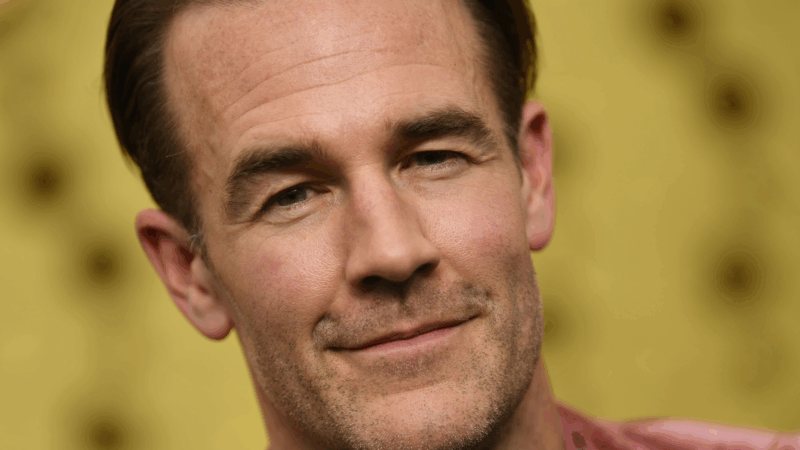

‘Dawson’s Creek’ star James Van Der Beek has died at 48

Van Der Beek played Dawson Leery on the hit show Dawson's Creek. He announced his colon cancer diagnosis in 2024.

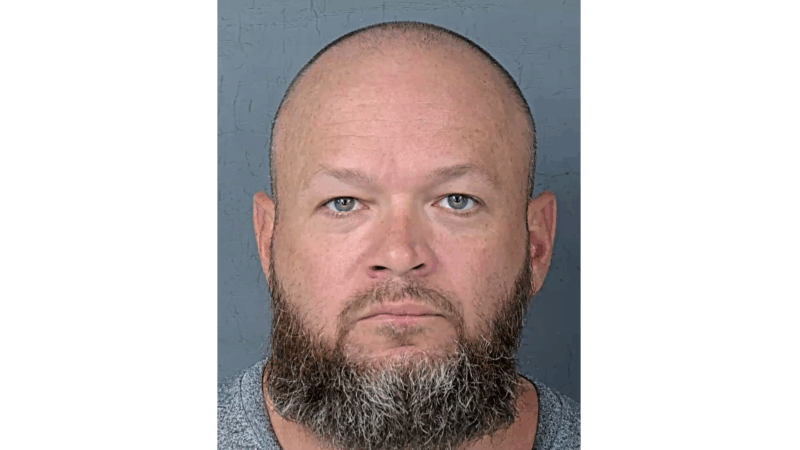

A Jan. 6 rioter pardoned by Trump was convicted of sexually abusing children

A handyman from Florida who received a pardon from President Trump for storming the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, was convicted on state charges of child sex abuse and exposing himself to a child.

A country-pop newcomer’s debut is your reinvention album of 2026

August Ponthier's Everywhere Isn't Texas is as much a fully realized introduction as a complete revival. Its an existential debut that asks: How, exactly, does the artist fit in here?

U.S. unexpectedly adds 130,000 jobs in January after a weak 2025

U.S. employers added 130,000 jobs in January as the unemployment rate dipped to 4.3% from 4.4% in December. Annual revisions show that job growth last year was far weaker than initially reported.