Charity-seekers from all over Pakistan flock to Karachi at Ramadan to collect alms

KARACHI, Pakistan — On a recent Monday afternoon, 61-year-old Sayani Soomar, a widow, sits on a curb in a busy Karachi commercial area with a paper sign asking for help. She holds in her lap packages with pills for high blood pressure, her husband’s death certificate and an electricity bill — evidence of her need. Since quitting her job as a housekeeper in Karachi around five years ago because of knee pain, Soomar says she has often resorted to begging to cover her expenses.

This month, Soomar says she’s come to the streets to ask for zakat, an obligatory form of charity in Islam for people with wealth above a certain threshold. It’s earmarked for the poor and needy and often given out during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan. During this time of year, Soomar says people can be generous, but getting donations depends on being in the right place at the right time. “Many people are giving charity,” she says. “We may try our luck.”

Sitting with Soomar on the curb is her young granddaughter, whom Soomar went by bus to pick up from Qazi Ahmed, a town around 170 miles away, to join her for Ramadan. The two plan to return to Qazi Ahmed after Eid, the holiday marking the end of Ramadan, which begins in Pakistan today.

Islam’s holiest month is known for increased generosity. And in Pakistan’s largest city and financial hub, the spirit of Ramadan has also fueled a migration trend among those seeking charity. It’s estimated that tens of thousands converge on this port megacity during Ramadan to collect alms.

Faisal Edhi, chairman of the Edhi Foundation, Pakistan’s best-known charity organization, says there are entire communities of what he calls “habitual” beggars who travel to Karachi during Ramadan and return to their hometowns soon after. “They [stay] here, they make money and they go back,” he says.

The annual influx of charity-seekers to Karachi is not a new phenomenon, but it has gained increased government attention this year as Pakistan steps up efforts to curb begging. A bill passed by Pakistan’s Senate last month expands the definition of trafficking to include organized begging and includes a prison term of up to 10 years for anyone who lures or forces others into begging. In Karachi, police are advised to move children found begging to child protection centers, to be looked after by the Sindh provincial social welfare department.

The national government is also taking steps to stop begging by its citizens abroad, after recent complaints from Gulf nations including Saudi Arabia. The kingdom says beggars arrive under the guise of religious pilgrimage, prompting Pakistan last year to block more than 4,000 from traveling there. Last week, Pakistani authorities also arrested the alleged head of a criminal network it accuses of trafficking women to Saudi Arabia. The Federal Investigative Agency says the women were forced into begging after being promised free passage for the Umrah pilgrimage.

Around 25% of Pakistan’s population lived below the poverty line last year, according to the World Bank, and economists say major structural challenges are contributing to this.

The country is slowly recovering from a years-long economic crisis and is still struggling to create opportunities for unskilled workers, says Karachi-based economist Ammar Khan. “We do not have any significant or serious growth happening in either the modernization of agriculture or industrialization of the country,” he says.

Laws against begging are loosely enforced

Philanthropy is especially evident during Ramadan, as charity organizations in Karachi provide food rations to the needy and free meals before and after the day-long fast.

Near one public iftar meal to break the fast, next to a well-known Sufi shrine, a group of longtime beggars mixes with newcomers. Some have arrived from as far away as Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province on the other side of the country. They disagree about the generosity of Karachi residents: Some regulars insist it’s minimal, but a boy from Chiniot, a city in Punjab province to the north, says he saw another child earn 5,000 Pakistani rupees, around $18, in one outing during Ramadan — a large sum compared to what unskilled laborers earn in a day.

It’s hard to pinpoint how many people come to Karachi to seek charity during Ramadan, says the city’s Mayor Murtaza Wahab. He says there are no official figures for these seasonal migrants. But he suggests that the number who come to beg during Ramadan could be even more than the 10,000 people who he estimates come to Karachi per day for any reason in a normal month. Karachi’s police were unable to provide a number of charity seekers who come from outside the city during this time or any other time of year.

Begging has been illegal in Pakistan since 1958 and can carry a jail sentence of up to three years. The practice remains common — and authorities say those involved are often part of criminal networks that force children into begging by trafficking them. Over the years, Pakistan’s provinces have tried to crack down on criminal groups targeting minors by tightening child protection laws. The provincial government in Karachi also vowed this year to take action against so-called professional beggars — those who make a living by begging — and has arrested 220 people so far during this Ramadan.

In general, laws related to begging are loosely enforced, and people arrested in Karachi are often released by courts after a verbal warning or a minor fine, says Asad Raza, deputy inspector general of police for the city’s affluent South Zone. “The law enforcement agencies as well as the courts, they are not very strict about [laws’] implementation,” he says.

Some come to Karachi seeking work at Ramadan, but end up begging instead

Although some Karachi residents frown on the practice of begging, many are still happy to give to those who ask for money, especially during Ramadan. Outside a bakery in the upscale Defense Housing Authority neighborhood, 24-year-old Naveed Ali hands a bill out the window of his car to a a young woman seeking alms. “Leaders have made things expensive,” he says. “Every person is poor and can’t earn or is unemployed. Because of this, they are compelled to do this. If they ask in the name of Allah, I give it.”

Several men say they came to Karachi during this Ramadan not to beg, but in hopes of finding daily wage work. Muhammad Younus, 28, arrived from the city of Tando Adam, around 130 miles away. He’s among dozens of people gathered under a tent for iftar, while workers from a charity organization serve heaping plates of biryani from a big metal pot.

He says he makes this trip annually because working odd jobs in Karachi can fetch two to three times the 500 rupees, about $2 a day, he earns at home. He uses the extra cash to buy gifts for his children for Eid.

But after failing to find work in Karachi this year, he has resorted to staying in the streets and living off charity. He reluctantly admits he is accepting money from people passing by.

“I am not a beggar,” he says, “but circumstances have overwhelmed me. I only ask people to help me.”

Transcript:

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

For the past month, Muslims around the world have been observing Ramadan, a time known for increased giving. But in Pakistan’s largest city, the spirit of Ramadan has also fueled a unique and controversial migration trend among charity-seekers. Betsy Joles has more from Karachi.

(SOUNDBITE OF HORN HONKING)

BETSY JOLES, BYLINE: Sixty-one-year-old Sayani Soomar (ph) sits on the curb in a busy commercial area in Karachi holding a pile of medication and a paper sign asking for help.

SAYANI SOOMAR: (Non-English language spoken).

JOLES: She says she’s sick and needs food rations. So this afternoon, she came to the streets to ask for zakat, an obligatory form of charity in Islam for those with enough wealth reserved for the poor and needy. It’s often given out during the month of Ramadan, which started in Pakistan in early March.

(SOUNDBITE OF PAPERS RUSTLING)

JOLES: Soomar shows NPR an electricity bill and a medical report she says is for her high blood pressure. For these expenses, she says, she often resorts to begging. Soomar says Ramadan can be a fruitful time for it.

SOOMAR: (Through interpreter) Many people are giving charity. We may try our luck.

JOLES: Every year, people from around Pakistan flock to Karachi during Ramadan to collect charity, banking on increased generosity from people in the country’s financial hub. Ramadan comes this year during a period of economic recovery in Pakistan, but many people are still struggling to get by.

AMMAR KHAN: It’s important to understand that Pakistan’s labor force, it’s fairly informal and unskilled. So if you’re an unskilled labor force, it’s difficult to get a better price for your services.

JOLES: This is economist Ammar Khan. He says, despite on-paper improvements, Pakistan is facing major structural challenges that limit opportunities for its working class.

KHAN: We do not have any significant or serious growth happening in either modernization of agriculture or industrialization of the country.

JOLES: Begging is illegal in Pakistan, though laws against it are loosely enforced. Police say there exist criminal networks that force children into the business by trafficking them. This month, the government in Karachi has arrested 220 people who they call professional beggars – in other words, those who make a living out of begging. But even though begging is socially frowned upon, many in Karachi are still willing to give money to those who ask for it, especially during Ramadan.

(SOUNDBITE OF METAL CLANKING)

JOLES: Around sunset, dozens of people gather under a tent for iftar, the meal that breaks the daylong fast during Ramadan. Workers from a charity organization serve heaping plates of biryani from a big metal pot.

(SOUNDBITE OF UTENSILS CLATTERING)

JOLES: Twenty-eight-year-old Muhammad Younus (ph) is among the people who’ve come for a free meal.

MUHAMMAD YOUNUS: (Through interpreter) I am not a beggar, but circumstances have overwhelmed me.

JOLES: He says he travels to Karachi every year during Ramadan from his hometown, around 3 1/2 hours away. He usually looks for daily wage work, but after failing to find any, he’s resorted to staying in the streets.

YOUNUS: (Through interpreter) I only ask people to help me.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

UNIDENTIFIED MUSICAL ARTIST: (Singing in non-English language).

JOLES: Around 100 meters away from the iftar, people are collecting money near a well-known shrine from the Sufi tradition of Islam, which people hold in reverence because of the saint that’s buried there. One Urdu word used for beggars, fakir, can also refer to religious ascetics who give up worldly possessions and exist on donations to strengthen their connection with God. Abdul Rashid (ph), a 47-year-old who traveled nearly eight hours to Karachi for Ramadan, says he’s here to bring the saint his troubles.

ABDUL RASHID: (Through interpreter) Because they are saints, and saints are the friends of Allah, everyone comes to them in the name of Allah.

JOLES: He says he hopes God will grant him what he needs. And for that, help might come from the people of Karachi.

With Sameer Mandhro, for NPR News, I’m Betsy Joles in Karachi, Pakistan.

(SOUNDBITE OF DE LA SOUL AND USHER SONG, “GREYHOUNDS”)

Can’t decide what to read next? Here are 20 recommendations for your book club

You know that feeling when you finish a book and just have to discuss it with someone? That's a great book club book. Here are 20 tried-and-true titles that are sure to get the conversation started.

The risks of AI in schools outweigh the benefits, report says

A new report warns that AI poses a serious threat to children's cognitive development and emotional well-being.

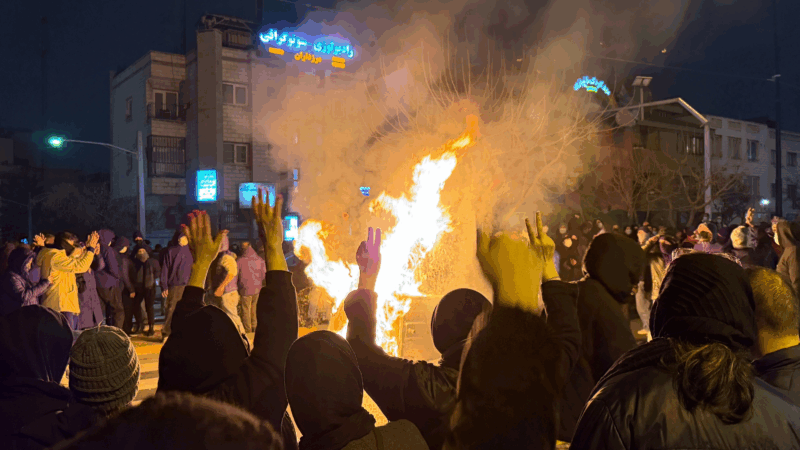

The death toll from a crackdown on protests in Iran jumps to over 2,500, activists say

The number of dead climbed to at least 2,571 early Wednesday, as reported by the U.S.-based Human Rights Activists News Agency, as Iranians made phone calls abroad for the first time in days.

How have prices changed in a year? NPR checked 114 items at Walmart

We found the effects of tariffs and extreme weather, relief (finally!) in the egg cooler, plus one case of shrinkflation.

The long-term health impacts from the LA wildfires are just becoming clear

The fires affected millions of people in the region. It could take years to understand the health consequences, but ongoing research is helping to prepare people to weather the next fires more safely.

How the feud between Trump and Minnesota is impacting the probe into the ICE shooting

The FBI is solely leading the inquiry into the killing of Renee Macklin Good by ICE agent Jonathan Ross without help from Minnesota authorities. Legal experts explain why the move is unusual and why joint investigations are the norm.