Access to Ukraine’s rare earths may help keep U.S. aid flowing

KYIV — As the Trump administration publicly hammers out its plans on ending Russia’s war on Ukraine, it’s also pressing Ukraine for deals in exchange for more aid.

One deal in the works would hand the U.S. the right to mine critical minerals including rare earth metals, which are used in a variety of products including laptops, electric vehicle batteries and cancer treatment drugs.

China holds a third of the world’s rare earth metal reserves, according to the United States Geological Survey, and is by far the world’s largest producer. Ukraine has some of the larger deposits of rare earths and critical minerals in Europe.

Estimates vary of Ukraine’s mineral wealth value. In interviews with the New York Post and Fox News, Trump has estimated that the country’s critical minerals and rare earths are worth between $500 million and $500 billion. Volodymyr Landa, senior economist at the Centre for Economic Strategy in Kyiv, told NPR that he led a survey of all mineral resources in Ukraine for Forbes Ukraine in 2023 and estimated their value at $14.8 trillion — an estimate cited by the Ukrainian government as well. (Other estimates have run even higher).Speaking to Fox News earlier this week, Trump said he told Ukrainian officials he wants to exchange mineral rights for continued American aid.

“And they’ve essentially agreed to do that,” he said. “So at least we don’t feel stupid. Otherwise we’re stupid. I said to them, we have to get something, we can’t keep paying this money.”

Ukraine and the U.S. are still working out the prospective deal. The Trump administration’s special envoy is set to visit Ukraine next week.

President Trump sent his Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent to Kyiv earlier this week to discuss a mining deal with Zelenskyy and other members of the Ukrainian government. Bessent framed it as the U.S. and Ukraine deepening economic ties.

“This is an important signal — to the world, to the Russian leadership — that we stand together,” Bessent told reporters.

Zelenskyy first brought up the idea to Trump last fall, when Trump was a presidential candidate. Speaking at the Munich Security Conference in Germany on Friday, Zelenskyy said such a deal would give Ukraine security guarantees.

“We need to protect Ukraine and our resources,” he said. “Why do we need to protect them? So that they do not fall into the hands of Russia and their allies.”

Russia has taken over parts of eastern Ukraine that include raw material deposits and mines. Intense fighting around the eastern Ukrainian city of Pokrovsk forced the closure of Ukraine’s last operating coking coal mine.

South Carolina Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham, who is also in Munich, framed the prospective deal as a way to pressure Russian President Vladimir Putin into concessions.

“Putin doesn’t understand what’s going on,” Graham told conference attendees in Munich. “If we sign this minerals agreement, Putin is screwed, ’cause Trump will defend the deal.”

Landa, the economist, told NPR that he expects American investors will be interested in two critical minerals — titanium, which is used in aviation, and lithium, which is used in electronics. He hopes a large part of the production chain stays in Ukraine.

“If an American company opens not just a mine but a lithium enrichment factory for example, that’s very good,” he says. “That’s definitely a win-win situation, when American investors will get revenues … a predictable supply chain. And Ukraine will get jobs, will get taxes.”

While some lithium deposits lie in Russian-occupied parts of Ukraine and close to the front line, Landa says others are safe and undeveloped. He says NEQSOL, a company based in Azerbaijan, bought the holding rights to two big deposits of titanium this fall.

Kurt Volker, a longtime diplomat who served as the U.S. special representative to Ukraine in the first Trump administration, is on NEQSOL’s advisory board, according to the company’s website.

Liudmila Tsyganok, president of the Professional Association of Environmentalists of Ukraine, warns that processing critical minerals creates sludge that, if stored improperly, can contaminate soil and groundwater.

“This moment will be extremely important for Ukraine,” she says. “How to prevent environmental disasters? You need to involve scientists.”

Protecting the environment may only be feasible up to a point, especially as Russia advances on Ukrainian land that includes key rare earth deposits, Dmytro Kuleba, a former foreign minister in Zelenskyy’s administration, told NPR in an interview.

“If I have to choose between the threat of contaminating these territories with Russia or contaminating them with the byproducts of the exploration of raw materials,” he said, “I would definitely go for the second option.”

NPR producers Polina Lytvynova and Hanna Palamarenko contributed to this report from Kyiv.

Despite the pause on high tariffs, Chinese factories still face high uncertainty

A 90-day pause on triple-digit U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods has left exporters and importers in a high state of uncertainty. Factory owners in China tell NPR that orders are down overall.

Trump administration moves to cancel remaining federal funds to Harvard

A letter from the U.S. General Services Administration, which is dated Tuesday, tells agencies to submit a list of contracts they have terminated with the university by June 6.

NPR and Colorado public radio stations sue Trump White House

NPR and three Colorado public radio stations are suing the Trump administration over the president's executive order seeking to ban the use of federal money for NPR and PBS.

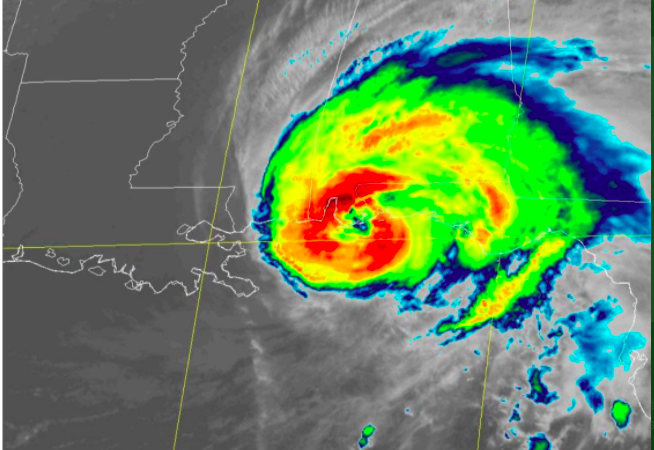

Alabama study reveals hurricane resilience programs are paying off for homeowners and insurers

The first-of-its-kind analysis, released last week, reviews thousands of insurance claims linked to Hurricane Sally, which struck Alabama’s coast in 2020. Homes retrofitted or built to Fortified standards saw significantly fewer and less costly claims.

Are manufacturing jobs actually special?

More than half of American workers don't have a college degree. Is manufacturing a ticket for them to the middle class?

Why Japan sees President Trump’s tariffs as a ‘national crisis’

Although largely paused, President Trump's tariffs present a major threat to Japan's already flagging economy.