A day in the life of one migrant seeking to stay in the U.S.

INDIO, Calif. — When the nurse told Yasmelin Velazquez she was going to be hospitalized for a couple of days, Velazquez’s anxiety spiked.

“I can’t stay!” she exclaimed. “I have immigration court tomorrow!”

The hospitalization comes at a bad time. Missing her first court hearing the next day would almost guarantee a deportation order for the 36-year-old Venezuelan immigrant and her two young sons.

She’s especially on edge since receiving an email from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security two days earlier notifying her that her temporary status in the country was terminated.

“It is time for you to leave the United States,” the email read. “Do not attempt to remain in the United States — the federal government will find you.”

Velazquez is among the growing number of migrants who received the DHS email. All of them came to the U.S. through legal pathways now terminated by President Trump, or were given temporary protection from deportation after surrendering to immigration authorities at the U.S.-Mexico border.

They are now left in limbo: Should they stay and continue the legal process? Could they be detained or deported while waiting for their day in court?

NPR has followed Velazquez’s immigration journey from Ciudad Juárez, México, where she waited 8 months to enter the U.S. via the CBP One app, a Biden-era legal pathway for asylum seekers. She became one of 900,000 people who used the app, which was the only way to schedule an immigration hearing in the U.S. at the time.

But as her court date approached, Velazquez told NPR she was getting nervous. Migrants have been picked up by immigration authorities at court lately, and that could happen to her, too.

Then, her doctor called during Velazquez’s shift at Walmart. The doctor explained that she had some bad test results and might need to stay in the emergency room for a couple of days.

After pushing back, Velazquez was cleared to leave the hospital. She will make it to court the next day – but the doctor warns her condition could worsen.

The sun had not risen when Velazquez, her partner, and her two little boys, 2-year-old Jeremías and 4-year-old Jordan, left their home in Indio, California, the next day.

“Father God, be our lawyer, be our judge,” they prayed. “Touch the heart of Judge Simmons.”

They are anxious — so they sing while they drive their used black SUV down the highway.

After more than two hours on the road, the family pulls up at the immigration court in an industrial park in a Southern California suburb.

A dozen or so other families make their way into the courtroom.

First hearings like this one are usually low-stakes. A judge validates the migrants’ identities, and they decide whether to file for a form of relief, such as asylum. Then a second hearing is scheduled.

But under Trump, anything can happen.

Inside the courtroom, Velazquez and the kids sit in the first row of wooden benches. They wait an hour for their turn– long enough that the two-year-old pees his pants.

Finally, the judge asks Velazquez whether she understands the reason she’s in court: that the government believes she doesn’t have a legal right to be in the U.S.

“Yes,” she replies quietly, adding that she’s planning to claim asylum later this summer.

The judge tells her to come back in August, this time with an attorney.

The whole interaction only took a few minutes.

Velazquez is free to go.

“I feel victorious,” she tells NPR after the hearing, her relieved laughter ringing over the parking lot while her kids snack on juice and arepas.

But their day isn’t over yet.

Next is another hour-long drive to Velazquez’s regular in-person check-in with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which she has to do every few months in addition to weekly calls and texts with the agent in charge of her parole.

This week, the check-in seems scarier. There have been reports of migrants being picked up by agents as they go into the ICE office. And now, there’s that email from DHS to worry about.

Velazquez enters the office and meets with the agent assigned to her case.

Eight minutes later, she comes out again, beaming a huge smile.

“Today, my future looks marvelous,” she says.

She was not detained today, but her optimism might be premature.

She has a long way to go in her quest for legal status, and the Trump administration is unpredictable and willing to push legal limits to fulfill its goal of deporting millions of people.

But Velazquez knows that when you are living day-to-day in the U.S., you take a win when you can.

“I feel like I’ll be able to obtain permanent residency, and who knows, maybe citizenship, too!” she says, laughing and smiling.

Transcript:

SCOTT SIMON, HOST:

It is time for you to leave the United States. That’s from an email sent by the Department of Homeland Security on Monday to migrants in the U.S. who hope to get asylum. When Yasmelin Velazquez saw this email, she panicked. NPR’s Sergio Martínez-Beltrán has been following her story for 10 months because it is a window into what asylum-seekers have been dealing with over the last year.

SERGIO MARTÍNEZ-BELTRÁN, BYLINE: Like many Venezuelans, 36-year-old Yasmelin Velazquez fled her country looking for a better life.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

YASMELIN VELAZQUEZ: (Speaking Spanish).

MARTÍNEZ-BELTRÁN: That’s Velazquez in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, when I met her last summer. She told me that she was looking for a way out of Venezuela’s socioeconomic problems and dictatorship. And that meant waiting for her immigration appointment, booked through the CBP One app, a legal pathway, and at that time, the only way to get an appointment.

VELAZQUEZ: (Speaking Spanish).

MARTÍNEZ-BELTRÁN: She waited seven months in Mexico before becoming one of 900,000 people who used the app to schedule an immigration hearing in the U.S., and that effort was finally going to pay off this week. Velazquez was scheduled to have her first immigration court hearing. But then that email from DHS told people to self-deport or else, and that’s confusing.

VELAZQUEZ: (Speaking Spanish).

MARTÍNEZ-BELTRÁN: She told me she was nervous. Migrants have been picked up by immigration authorities at court lately, and that could happen to her. As I board my flight to meet her in California, I receive a text message from her. She’s in the hospital. She got some bad test results, and her doctor has said she might need to stay in the emergency room for a couple days. It’s bad timing. Missing her court hearing would almost guarantee a deportation order.

(SOUNDBITE OF HOSPITAL MONITOR BEEPING)

VELAZQUEZ: (Speaking Spanish).

MARTÍNEZ-BELTRÁN: “I have court tomorrow. I can’t stay,” she tells the doctor. She convinces them to clear her. She will make it to court tomorrow, but the doctor warns her condition could worsen.

AUTOMATED VOICE: (Speaking Spanish).

UNIDENTIFIED CHILD #1: (Speaking Spanish).

(SOUNDBITE OF CAR DOOR CLOSING)

AUTOMATED VOICE: (Speaking Spanish).

UNIDENTIFIED CHILD #2: (Speaking Spanish).

MARTÍNEZ-BELTRÁN: The sun has not risen when Velazquez and her two little boys, ages 2 and 4, leave their home in Indio, California the next day.

VELAZQUEZ: (Speaking Spanish).

MARTÍNEZ-BELTRÁN: They start the long car ride with a prayer.

VELAZQUEZ: (Speaking Spanish).

MARTÍNEZ-BELTRÁN: “Father God, please be our lawyer. Please be our judge.”

VELAZQUEZ: (Speaking Spanish).

MARTÍNEZ-BELTRÁN: “God, touch the heart of Judge Simmons.”

VELAZQUEZ: (Speaking Spanish). Amen.

UNIDENTIFIED CHILD #1: Amen.

MARTÍNEZ-BELTRÁN: They are anxious, so they sing while they drive their used black SUV down the highway.

YASMELIN VELAZQUEZ, UNIDENTIFIED CHILD #1 AND UNIDENTIFIED CHILD #2: (Singing in Spanish).

MARTÍNEZ-BELTRÁN: They pull up at the immigration court in an industrial park in a southern California suburb. A dozen or so other families make their way into the courtroom. Usually, this first hearing is pretty low stakes. A judge validates their identity. The migrant says whether they will file for a relief, like asylum, and a second hearing is scheduled. But under Trump, anything can happen. There’s no recording allowed inside. Velazquez sits in the first row of wooden benches. Her 2-year-old pees his pants. After an hour, the judge turns to them and asks, do you understand that the government believes you don’t have a legal right to be in the U.S.? She says yes, but she adds she’s planning to claim asylum. The judge says come back in August – this time with an attorney. The whole interaction only takes a few minutes. For now, she’s free to go.

VELAZQUEZ: (Speaking Spanish).

MARTÍNEZ-BELTRÁN: “I feel victorious,” she says. But the day is not over.

VELAZQUEZ: (Speaking Spanish, laughter).

(SOUNDBITE OF CAR STARTING)

MARTÍNEZ-BELTRÁN: Next, another hourlong drive for her regular check-in with ICE. Lately, it’s become scarier. There have been reports of migrants being picked up by agents as they go into the ICE office. She goes into the office. She comes out eight minutes later, beaming.

VELAZQUEZ: (Speaking Spanish).

MARTÍNEZ-BELTRÁN: “Today, my future looks marvelous,” she says. She was not detained.

VELAZQUEZ: (Speaking Spanish, laughter).

MARTÍNEZ-BELTRÁN: “I feel I will be able to become a resident. And who knows, maybe a citizen,” she says. Her optimism might be premature. She has a long way to go, and the Trump administration is unpredictable and willing to push legal limits to fulfill its goal of deporting millions of people. But when you’re living day-to-day in the U.S., you take a win when you can.

Sergio Martínez-Beltrán, NPR News, San Bernardino, California.

Crackdown on dissent after nationwide protests in Iran widens to ensnare reformist figures

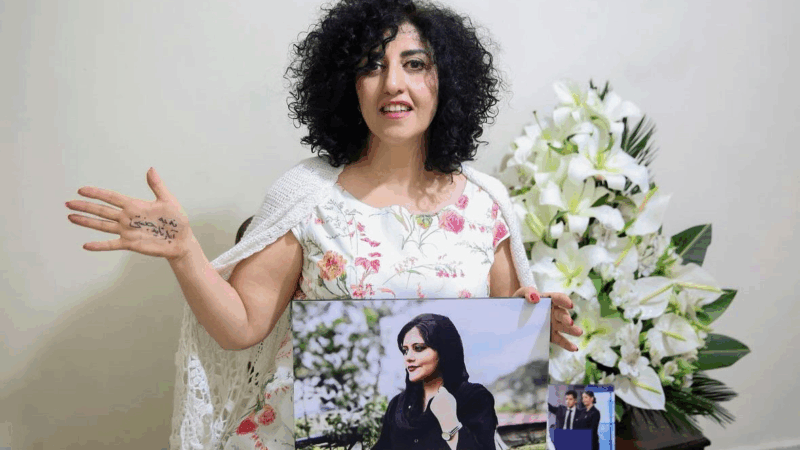

Detained Nobel Peace Prize laureate Narges Mohammadi has received another prison sentence of over seven years.

Crackdown on dissent after nationwide protests in Iran widens to ensnare reformist figures

Detained Nobel Peace Prize laureate Narges Mohammadi has received another prison sentence of over seven years.

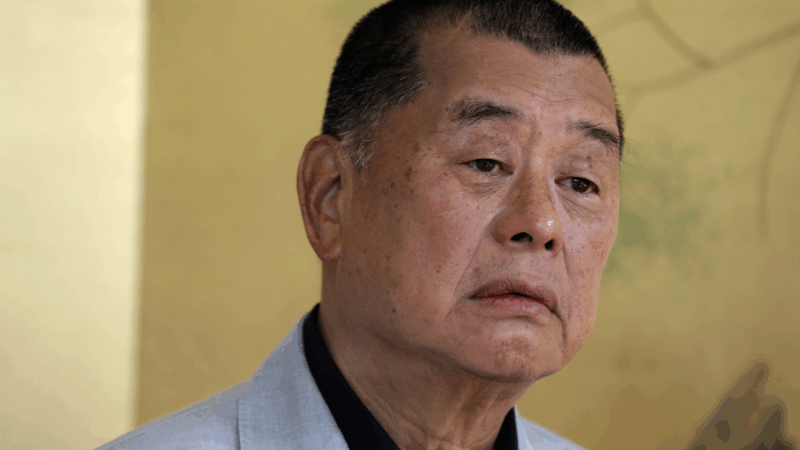

China critic and former media tycoon Jimmy Lai is sentenced to 20 years in a Hong Kong security case

Jimmy Lai, the pro-democracy former Hong Kong media tycoon and a fierce critic of Beijing, was sentenced on Monday to 20 years in prison in the longest punishment given so far under a China-imposed national security law that has virtually silenced the city's dissent.

China critic and former media tycoon Jimmy Lai is sentenced to 20 years in a Hong Kong security case

Jimmy Lai, the pro-democracy former Hong Kong media tycoon and a fierce critic of Beijing, was sentenced on Monday to 20 years in prison in the longest punishment given so far under a China-imposed national security law that has virtually silenced the city's dissent.

Center-left Socialist candidate wins over populist in Portugal’s presidential runoff

Center-left Socialist candidate António José Seguro recorded a thumping victory over hard-right populist André Ventura in Portugal's runoff presidential election Sunday, according to official results.

Seahawks win Super Bowl title, pounding the Patriots 29-13

Seattle's "Dark Side" defense helped Sam Darnold become the first quarterback in the 2018 draft class to win a Super Bowl, to win the franchise's second title.