5 ways the pandemic changed us for good, for bad and forever

As we mark five years on from the start of the coronavirus pandemic this month, life has changed for many people, in ways both mundane and profound.

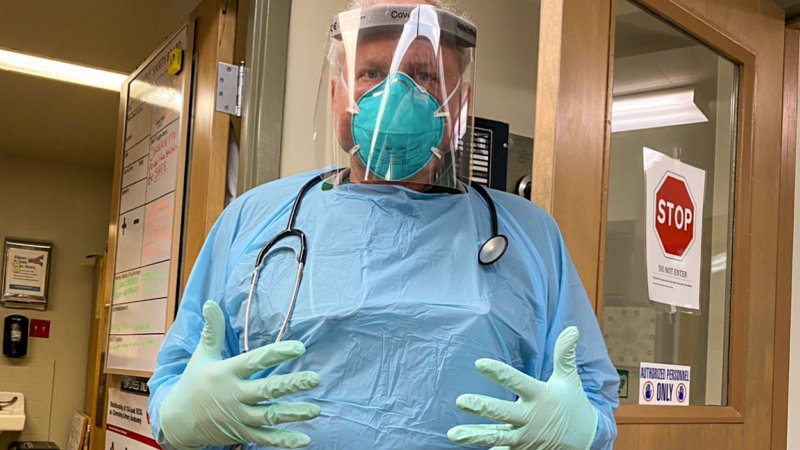

Dr. Kurt Papenfus is someone NPR interviewed in 2020. The CEO of a small hospital in rural Colorado, Papenfus first took care of COVID patients, then he became one. He told us the story of driving himself to Denver — with an escort of sheriff’s deputies to make sure he made it — so he could get the intensive care he knew he needed for COVID pneumonia.

“The ‘rona beast is a very nasty beast,” he said back then. “It has a very mean temper. It loves a fight, and it loves to keep coming after you.”

Papenfus now praises the investment in research that, he believes, advanced science by decades in just a few years. Personally, he has struggled with the brain fog of long COVID, and he has learned a lesson about conserving his energy.

“COVID was a harsh reminder that, ‘Yeah, you better take care of yourself. If you can’t take care of yourself, how are you going to take care of other people?'” Papenfus says.

Here are five more examples of lessons we have learned and things COVID changed permanently, though it is not an exhaustive list:

1. Video calls made the room bigger, distances shorter.

Has this happened to you? You’re watching something on Netflix from, say, 2018. There’s a video conference call in the story line and it’s presented as something odd, cool, unusual.

The pandemic changed that for everyone.

Zoom and other video conference apps became a common part of business and personal life.

Despite the occasional frozen screen glitches and folks joining calls in their ratty pajamas, there are upsides.

Beth Hendrix, executive director of the League of Women Voters of Colorado, said the use of remote conferencing led her group to become truly statewide. It allowed more meaningful participation for folks from the eastern plains to the west side of Colorado, called the Western Slope.

Before, all their meetings were in person, which “kept folks outside of the metro from really taking part in leadership actions. So that is one positive thing.”

Michael Dougherty, Boulder County’s district attorney, saw a similar silver lining: Virtual court proceedings allowed a lot more people to take part.

“We also have victims who are scared to be in the same room as a defendant or his loved ones,” he said. “They now can attend court virtually without the defendant even knowing they’re there.”

2. Pandemic pups brought us two-legged friends, too.

Many people became pet owners for the first time during the pandemic. Grace Markley, from Denver, said one of the surprising and beautiful things of the crisis was “we ended up adopting a miniature bernedoodle.”

She met neighbors who also adopted pandemic dogs. They hung out outside, socialized over potlucks and happy hours, connected over the canines and formed what they called their Doodlefest. It became a regular gathering, a holiday card featuring poodle-mix doggos, and a group chat. “And to date there are 22 of us on the chat,” Markley said.

“This part of town is just alive with pandemic puppies. So that was something that was really special for us. And five years in, we are still going strong,” Markley said.

3. Health inequities were exposed and so was vaccine hesitancy.

COVID exposed stark inequities in both society and the health system.

Julissa Soto, a health equity consultant, helped both spotlight and address them at hundreds of clinics around Colorado.

One instance was at Ascension Catholic Parish in Denver’s Montbello neighborhood, where in 2021, she told the masked congregation that COVID-19 vaccines are safe, effective and available.

“I’m on a mission to get my community vaccinated, and I will not stop until I get the last Latino vaccinated,” she said at the time.

Over the course of the pandemic, she helped get about 60,000 people vaccinated, by her count, at more than 400 vaccine clinics and events like the one at Ascension Catholic Church.

Fast forward to 2025, and Soto says it’s important to remember how many people were lost.

“Really sad, lots and lots of people died,” she said in an interview.

In Colorado, the number of people who died surpassed 16,000 people, according to figures reported by the CDC. More than 1.2 million people died across the country.

Most Coloradans got vaccinated, but the Latino community, which was hit hard by the virus, barely got to a 50% vaccination rate, Soto said. The low rate provided her “an opportunity to highlight the inequities. They have always existed in public health.”

During the 2024-2025 respiratory virus season, less than 25% of Colorado adults got the updated COVID-19 vaccine.

Among the lessons Soto said she learned in the pandemic: to pivot, think on her feet, remove barriers, challenge the status quo.

“I believe that we’re going to find solutions,” she said. “Remember from every setback, it will be a comeback.”

4. The classroom changed, and challenges set in.

For some, the dark clouds of the pandemic still exist. Melanie Potyondy, a public school psychologist in Fort Collins, says she’s noticed a troubling trend with kids: “a lack of resilience, a lack of that grit, that I think I saw in previous cohorts of kids prior to the pandemic.”

She says they’re now quicker to give up, quicker to write off a teacher they don’t click with. Add in a reliance on technology, which “compounds this diminished level of grit in that it’s so easy to hide out behind a phone and to not have to have difficult conversations with people in person.”

Schools have begun experimenting with cellphone bans during class, but the jury is still out on whether that will solve the learning challenges teachers and students have been reporting since the disruption of the pandemic.

5. Long COVID, too, appears here to stay.

“Hard to believe, five years later. Still in a little bit of recovery mode” is how Denver resident Clarence Troutman summed up his experience, both of getting COVID-19 and then long COVID.

Troutman was a broadband technician with CenturyLink, a telecom company, for 37 years. He caught the virus at the start of the pandemic, was hospitalized and on a ventilator for a time, and ended up staying in the hospital for two months.

Five years on, life is a mixed bag for Troutman, who had to retire from his job because of his health.

“I don’t have the neuropathy I used to have,” he says, citing a bright spot. That’s nerve damage causing pain, numbness or tingling.

“Kind of the psychological scars of everything have honestly kind of healed,” he says, noting the positive side of the ledger.

But he still grapples with chronic fatigue, brain fog and diminished lung capacity. Troutman says a long COVID patient group he joined after he got sick still meets regularly, comparing their experiences, supporting each other.

“We’re still a tight little group and we’re getting better together,” he says.

He’s started working out at his local rec center, thanks to his improving health. And he said he’s closer than ever to his son and two grandkids in Atlanta.

“I feel truly blessed every day when I think about the people that weren’t able to make it through this thing or changed forever, even worse than I am. I know I’m blessed,” he said. “I’m a very lucky guy.”

Troutman said another good thing was his discovery of an inner power.

“You kind of tap into a strength or resiliency you didn’t even know you had until all this happened,” Troutman said. “So yeah, it’s been quite the journey. Quite the journey.”

Transcript:

MARY LOUISE KELLY, HOST:

This week we’re thinking about five years ago, when the pandemic hit and changed the world. John Daley from Colorado Public Radio brings us this reflection from one front-line health provider who shared his experience from back then.

JOHN DALEY, BYLINE: Kurt Papenfus is a loquacious 67-year-old doctor. He practices on the rural Eastern Plains of Colorado. Five years ago, he was taking care of patients at the 10-bed Keefe Memorial Hospital in Cheyenne County. He’s still chief of staff and medical director there. But before vaccines were available, he himself caught coronavirus, as he told NPR in the fall of 2020.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

KURT PAPENFUS: The rona beast is a very nasty beast, and it is not fun. It has a very mean temper. It loves a fight, and it loves to keep coming after you.

DALEY: When he got sick, he drove himself three hours to Denver, followed by county deputies to make sure he made it to the hospital, where he was admitted with pneumonia. Today, he says the pandemic taught him plenty, including the importance of both the people who work the land in rural Colorado and those who provide their health care.

PAPENFUS: It reinforced pretty much taking care of the rural folks ’cause, with all the supply chains and stuff I was watching, those are the guys that really grow the food that the cities eat.

DALEY: He says the pandemic was rough, challenging and tragic, but also an opportunity to learn new things.

PAPENFUS: What do they call them, pivot points? It was a pivot point in history.

DALEY: It’s easy to forget now how many open questions there were at the start of the pandemic, he says, with no vaccine available.

PAPENFUS: I’ll tell you what though, in those five years it definitely advanced science by a couple decades. The federal spigot opened up to pour tons of money into research.

DALEY: Papenfus eventually developed long COVID, what he calls COVID brain. The experience was a wake-up call teaching him about self care, something he never learned in his medical education.

PAPENFUS: We were kind of trained to sacrifice yourself on the alter of medicine taking care of other people ’cause that’s the noble cause.

DALEY: He did return to work.

PAPENFUS: COVID was a harsh reminder that, yeah, you better take care of yourself ’cause if you can’t take care of yourself, how are you going to take care of other people?

DALEY: Dr. Kurt Papenfus says he has bounced back, but he’s also cut back his long hours at the hospital.

For NPR News, I’m John Daley in Denver.

Judge rules immigration officers in Minneapolis can’t detain peaceful protesters

Officers in the Minneapolis-area participating in a U.S. immigration enforcement operation can't detain or tear gas peaceful protesters who aren't obstructing authorities, a judge ruled Friday.

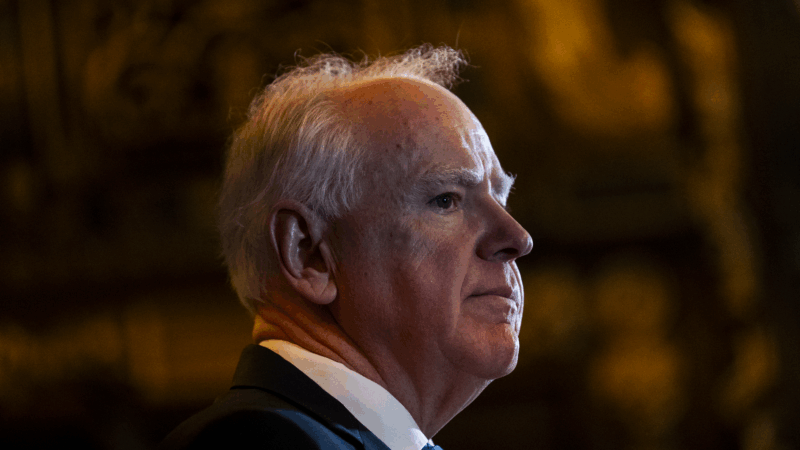

Justice Department opens investigation into Minnesota governor and Minneapolis mayor

Federal prosecutors are investigating Gov. Tim Walz and Mayor Jacob Frey.

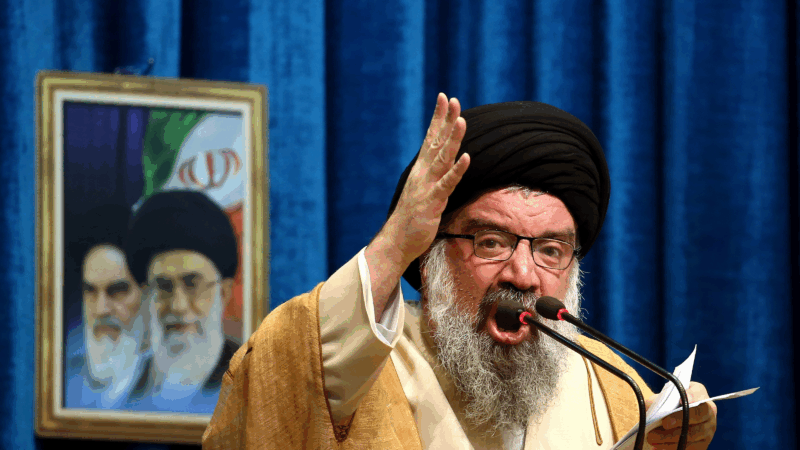

No sign of new protests in Iran as a hard-line cleric calls for executions

A Iran returns to an uneasy calm after protests led to a violent crackdown, a senior cleric is calling for the death penalty for detained demonstrators. His sermon Friday also threatened U.S. President Trump.

Gulf South food banks look back on a challenging year as another shutdown looms

Federal funding cuts and a 43-day government shutdown made 2025 a chaotic year for Gulf South food banks. For many, the challenges provide a road map for 2026.

Measles is spreading fast in S.C. Here’s what it says about vaccine exemptions

More than 550 people have contracted measles in Spartanburg County, S.C., in a fast-growing outbreak. Like a majority of U.S. counties, nonmedical exemptions to school vaccination are also rising.

It took 75 governors to elect a woman. Spanberger will soon be at Virginia’s helm

Abigail Spanberger, a former CIA officer and three-term congresswoman, is breaking long-held traditions on inauguration day. She says she wants her swearing-in to showcase the state's modern vibrancy.